Lake systems existing in regions over 10 million years ago survived the Amazon River reversal due to Andean uplift (image: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology)

Lake systems existing in regions over 10 million years ago survived the Amazon River reversal due to Andean uplift.

Lake systems existing in regions over 10 million years ago survived the Amazon River reversal due to Andean uplift.

Lake systems existing in regions over 10 million years ago survived the Amazon River reversal due to Andean uplift (image: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology)

By Peter Moon | Agência FAPESP – A land of giants. This is the best definition for Lake Pebas, a mega-wetland that existed in western Amazonia during the Miocene Epoch, which lasted from 23 million to 5.3 million years ago.

The Pebas Formation was the home of the largest caiman and gavialoid crocodilian ever identified, both of which were over ten meters in length, the largest turtle, whose carapace had a diameter of 3.5 meters, and rodents that were as large as present-day buffaloes.

Remains of the ancient biome are scattered over an area of more than 1 million square meters in what is now Bolivia, Acre State and western Amazonas State in Brazil, Peru, Colombia and Venezuela. The oldest datings in this biome are for fossils found in Venezuela and show that Lake Pebas existed 18 million years ago. Until recently, scientists believed that the mega-swamp dried up more than 10 million years ago, before the Amazon River reversed course. During most of the Miocene, this river flowed from east to west, opposite to its present direction. The giant animals disappeared when the waters of Pebas receded.

While investigating sediments associated with vertebrate fossils from two paleontological sites on the Acre and Purus Rivers, Marcos César Bissaro Júnior, a biologist affiliated with the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto School of Philosophy, Science and Letters (FFCLRP-USP) in Brazil, obtained datings of 8.5 million years with a margin of error of plus or minus 500,000 million years.

There is evidence that the Amazon was already running in its present direction 8.5 million years ago, draining from the Peruvian Andes into the Atlantic Ocean. By then, the Pebas system must have no longer resembled the magnificent wetlands of old. Rather, the system resembled a floodplain similar to the present-day Brazilian Pantanal. This is the view of Annie Schmaltz Hsiou, a professor in the Biology Department at FFCLRP-USP and supervisor of Bissaro Júnior’s research, which is described in a recently published article in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

The study was supported by FAPESP and Brazil’s National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). The participants also included researchers from the Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM), the Zoobotanic Foundation’s Natural Science Museum in Rio Grande do Sul, São Paulo State University (UNESP), the Federal University of Acre, and Boise State University in Idaho (USA).

The Pebas system encompasses several geological formations in western Amazonia: the Pebas and Fitzcarrald Formations in Peru and Brazil, the Solimões Formation in Brazil, the Urumaco and Socorro Formations in Venezuela, the La Venta Formation in Colombia, and the Quebrada Honda Formation in Bolivia.

“While the Solimões Formation is one of the best-sampled Neogene fossil-bearing stratigraphic units of northern South America, assumptions regarding deposition age in Brazil have been based largely on indirect methods,” Bissaro Júnior said.

“The absence of absolute ages hampers more refined interpretations on the paleoenvironments and paleoecology of the faunistic associations found there and does not allow us to answer some key questions, such as whether these beds were deposited after, during or before the formation of the proto-Amazon River.”

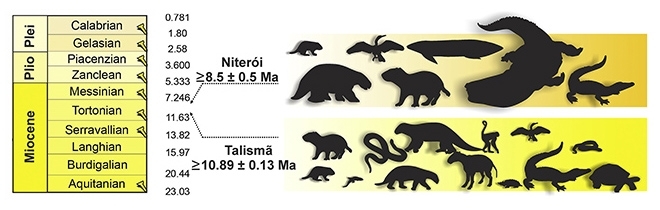

To answer these and other questions, Bissaro Júnior’s study presents the first geochronology of the Solimões Formation, based on mineral zircon specimens collected at two of the region’s best-sampled paleontological sites: Niterói on the Acre River in the municipality of Senador Guiomar and Talismã on the Purus River in the municipality of Manuel Urbano.

Since the 1980s, many Miocene fossils have been found at the Niterói site, including crocodilians, fishes, rodents, turtles, birds, and xenarthran mammals (extinct terrestrial sloths). Miocene fossils of crocodilians, snakes, rodents, privates, sloths, and extinct South American ungulates (litopterns) have been found in the same period at the Talismã site.

As a result of the datings, Bissaro Júnior discovered that the rocks at the Niterói and Talismã sites are approximately 8.5 million and 10.9 million years old (maximum depositional age), respectively.

“Based on both faunal dissimilarities and maximum depositional age differences between the two localities, we suggest that Talismã is older than Niterói. However, we stress the need for further zircon dating to test this hypothesis, as well as datings for other localities in the Solimões Formation,” he said.

Drying up of Pebas

Lake Pebas was formed when the land rose in the proto-Amazon basin as a result of the Andean uplift, which began accelerating 20 million years ago. At that time, western Amazonia was bathed by the Amazon (which then flowed toward the Caribbean) and the Magdalena in Colombia. The Andes uplift that occurred in what is now Peru and Colombia eventually interrupted the flow of water toward the Pacific, causing water to pool in western Amazonia and giving rise to the mega-wetland.

However, the Andes continued to rise. The continuous uplifting of land in Amazonia had two effects. The proto-Amazon, previously pent up in Lake Pebas, reversed course and became the majestic river we now know. During this process, water gradually drained out of the Pebas mega-swamp.

The swamp became a floodplain full of huge animals, which still existed 8.5 million years ago, according to new datings by Bissaro Júnior. Unstoppable geological forces eventually drained the remains of the temporary lagoons and lakes in western Amazonia. This was the end of Pebas and its fauna.

“The problem with dating Pebas has always been associating datings directly with the vertebrate fauna. There are countless datings of rocks in which invertebrate fossils have been found, but dating rocks with vertebrates in Brazil was one of our goals,” Schmaltz Hsiou said.

The new datings, she added, suggest that the Pebas system – i.e., the vast wetland – existed between 23 million and 10 million years ago. The Pebas system gave way to the Acre system, an immense floodplain that existed between 10 million and 7 million years ago, where reptiles such as Purussaurus and Mourasuchus still lived.

“The Acre system must have been a similar biome to what was then Venezuela, consisting of lagoons surrounding the delta of a great river, the proto-Orinoco,” she said.

Giant rodents

Rodents are a highly diversified group of mammals that inhabit all continents except for Antarctica. Amazonia is home to a large number of rodent species.

“In particular, a rodent group known scientifically as Caviomorpha came to our continent about 41 million years ago from Africa,” said Leonardo Kerber, a researcher at UFSM’s Quarta Colônia Paleontological Research Support Center (CAPPA) and a coauthor of the article published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

“In this period, known as the Eocene Epoch, Africa and South America were already totally separated, with at least 1,000 kilometers between the closest points of the two continents, so there couldn’t have been any biogeographical connections enabling terrestrial vertebrates to migrate between the two land masses,” Kerber said. “However, the ocean currents drove dispersal by means of natural rafts of tree trunks and branches blown into rivers by storms and swept out to sea. Some of these rafts would have borne away small vertebrates. An event of this kind may have enabled small mammals such as Platyrrhini monkeys, as well as small rodents, to cross the ocean, giving rise to one of the most emblematic groups of South American mammals, the caviomorph rodents.”

According to Kerber, the continent’s caviomorph rodents have undergone a long period of evolution since their arrival, becoming highly diversified as a result. In Brazil, the group is currently represented by the paca, agouti, guinea pig, porcupine and bristly mouse, as well as by the capybara, the world’s largest rodent.

“In Amazonia, above all, we now find a great diversity of bristly mice, porcupines, agoutis and pacas. In the Miocene, however, the Amazonian fauna was very different from what we can observe now,” Kerber said.

“In recent years, in addition to reporting the presence of many fossils of species already known to science, some of which had previously been recorded in the Solimões Formation and others that were known from other parts of South America but recorded in Solimões for the first time, we’ve described three new medium-sized rodent species (Potamarchus adamiae, Pseudopotamarchus villanuevai and Ferigolomys pacarana – Dinomyidae) that are related to the pacarana (Dinomys branickii).”

Kerber said an article to be published shortly in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology will recognize Neoepiblema acreensis, an endemic Brazilian Miocene neoepiblemid rodent that weighed some 120 kg as a valid species.

“The species was described in 1990 but was considered invalid at the end of the decade. These fossil records of both known and new species help us understand how life evolved in the region and how its biodiversity developed and experienced extinctions over millions of years in the past,” Kerber said.

The article “Detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology constrains the age of Brazilian Neogene deposits from Western Amazonia” (doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.11.032) by Marcos C. Bissaro-Júnior, Leonardo Kerber, James L. Crowley, Ana M. Ribeiro, Renato P. Ghilardi, Edson Guilherme, Francisco R. Negri, Jonas P. Souza Filho and Annie S. Hsiou can be retrieved from: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S003101821830405X.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.