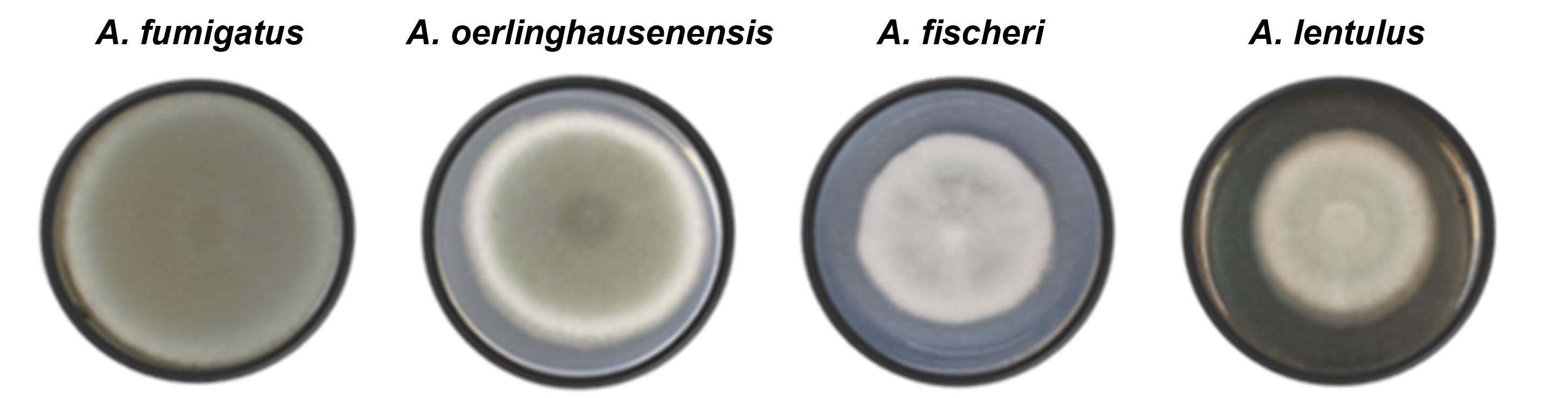

The pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus (far left) grew more than other species in a medium designed to mimic the human organism, partly owing to the presence of a protein that inhibits the immune system (photo: Rafael Sanchez Luperini/FCFRP-USP)

Researchers at the University of São Paulo found 62 proteins specific to spores of Aspergillus fumigatus, a fungal species that causes lung disease. The study, published in Nature Microbiology, showed that at least one of these proteins inhibits human defense mechanisms.

Researchers at the University of São Paulo found 62 proteins specific to spores of Aspergillus fumigatus, a fungal species that causes lung disease. The study, published in Nature Microbiology, showed that at least one of these proteins inhibits human defense mechanisms.

The pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus (far left) grew more than other species in a medium designed to mimic the human organism, partly owing to the presence of a protein that inhibits the immune system (photo: Rafael Sanchez Luperini/FCFRP-USP)

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is a life-threatening fungal infection that occurs when conidia (spores) from the Aspergillus fungus are inhaled and establish an infection in the lungs, particularly in individuals with a weakened immune system, allowing the fungus to spread beyond the lung tissue into the bloodstream. Treatment options are scant. When the specific pathogen is Aspergillus fumigatus, mortality can be as high as 90%.

Researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil compared the full set of proteins present on the surface of A. fumigatus conidia and other closely related species that do not necessarily cause infection. They identified 62 proteins found solely in A. fumigatus.

An article on the study is published in the journal Nature Microbiology. The research project was led by scientists at the Ribeirão Preto School of Pharmaceutical Sciences (FCFRP-USP).

One of the proteins identified was glycosylasparaginase, which drew the researchers’ attention owing to its ability to inhibit the production of immune cells. When mutants of the fungus that did not produce glycosylasparaginase came into contact with mouse cells, they triggered an increase in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines – proteins released by immune cells to alert the host to invading microorganisms.

In contrast, murine cells infected by the wild-type fungus, in which all genes functioned normally, did not secrete high levels of these cytokines, suggesting that glycosylasparaginase plays a major role in modulating and reducing cytokine production so that the fungus has time to initiate and consolidate the infection.

“This is the first study to characterize the role of glycosylasparaginase in fungi. In humans, the gene mutation that produces this enzyme causes a rare neurodegenerative disease [aspartylglucosaminuria], in which glycoasparagine accumulates in various tissues of the body, including the central nervous system. This causes developmental delay, psychomotor impairment, intellectual disability, and finally premature death. Unfortunately, there is no treatment for this disease,” said Camila Figueiredo Pinzan, first author of the article and a researcher at FCFRP-USP.

When the researchers infected mice separately with the wild-type fungus and the mutant version (which did not produce glycosylasparaginase), they found that the fungal burden in the lungs of the group infected with the mutant version was lower. “This could mean that lack of the enzyme glycosylasparaginase makes the fungus more prone to elimination by the immune system,” Pinzan said.

Potential

The study was part of a project supported by FAPESP and led by Gustavo Henrique Goldman, a professor at FCFRP-USP.

“Studies like this are fundamental to understand how fungi cause infection and identify novel potential targets for drug development. Conidia are the fungal cells that make first contact with the human respiratory system and initiate infection. These findings could represent a first step toward acquisition of the capability to combat the invasion in the initial stages,” Goldman said.

Glycosylasparaginase is only one of the 62 proteins identified in the study, he stressed. The others are being analyzed by his lab and exhibit varying degrees of promise as potential targets for future interventions.

Non-pathogenic

To find out which of these proteins were present in A. fumigatus but not in other species of Aspergillus, the researchers analyzed conidia of three other species using proteomics: A. fischeri and A. oerlinghausenensis, which do not cause disease in humans, and A. lentulus, which can cause disease but is much less virulent than A. fumigatus.

“Although the similarity between these species can reach 95%, A. fumigatus can kill up to 90% of infected individuals, whereas for the others there are no reports of human infection, except for A. lentulus, which rarely causes disease,” said Thaila Reis, penultimate author of the article and a researcher at FCFRP-USP.

Understanding how fungi cause infection and become more virulent is essential to combat known pathogens and others that may emerge. With this in mind, the research group analyzed A. fischeri, a species not usually considered pathogenic. The findings of this study are published in Communications Biology.

They assessed the pathogenic potential of 16 strains of A. fischeri, one of the four species analyzed previously, in experiments involving cell and animal models, concluding that some strains are in fact capable of causing infection.

For David Rinker, first author of this study and a professor at Vanderbilt University in the United States, “fungal pathogenicity is not considered obligate, but rather opportunistic. Therefore, the potential for new, opportunistic fungal pathogens to make the ‘leap’ into the clinic may be greater than we previously realized.”

Looking for shared mechanisms of virulence in “non-pathogens” may shed light on how pathogens originate or even predict the emergence of novel pathogens, Rinker is quoted as saying in a post to VU’s website.

“Both studies point to the need for a broader perspective on fungal virulence that includes species hitherto considered non-pathogenic. They may harbor a hidden potential to cause disease that emerges under certain environmental conditions or in immunosuppressed people,” Goldman said.

FAPESP also supported the study published in Nature Microbiology via five other projects (18/18257-1, 18/15549-1, 20/04923-0, 22/08796-8 e 22/13603-4).

Besides the grant awarded to Goldman, the study published in Communications Biology was supported by a scholarship from FAPESP. Both studies were also supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The article “Aspergillus fumigatus conidial surface-associated proteome reveals factors for fungal evasion and host immunity modulation” is at: www.nature.com/articles/s41564-024-01782-y.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.