Emerging pollutants include pesticides used in agriculture, fuel additives, plasticizers or non-stick materials, medicines, hygiene products and cosmetics (photo: Freepik*)

In addition to the scarcity and unequal distribution of water, quality is being strongly affected by agricultural pesticides, industrial waste, and the disposal of medicines and hygiene products.

In addition to the scarcity and unequal distribution of water, quality is being strongly affected by agricultural pesticides, industrial waste, and the disposal of medicines and hygiene products.

Emerging pollutants include pesticides used in agriculture, fuel additives, plasticizers or non-stick materials, medicines, hygiene products and cosmetics (photo: Freepik*)

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – As the population grows and urbanization and agro-industrial activity increase, the demand for freshwater is expected to rise by 55% by 2050. Experts project that this increase in demand will strongly impact a scenario already characterized by scarce and unequally distributed water resources, the privatization of an essential public asset, and deteriorating water quality, especially in developing countries.

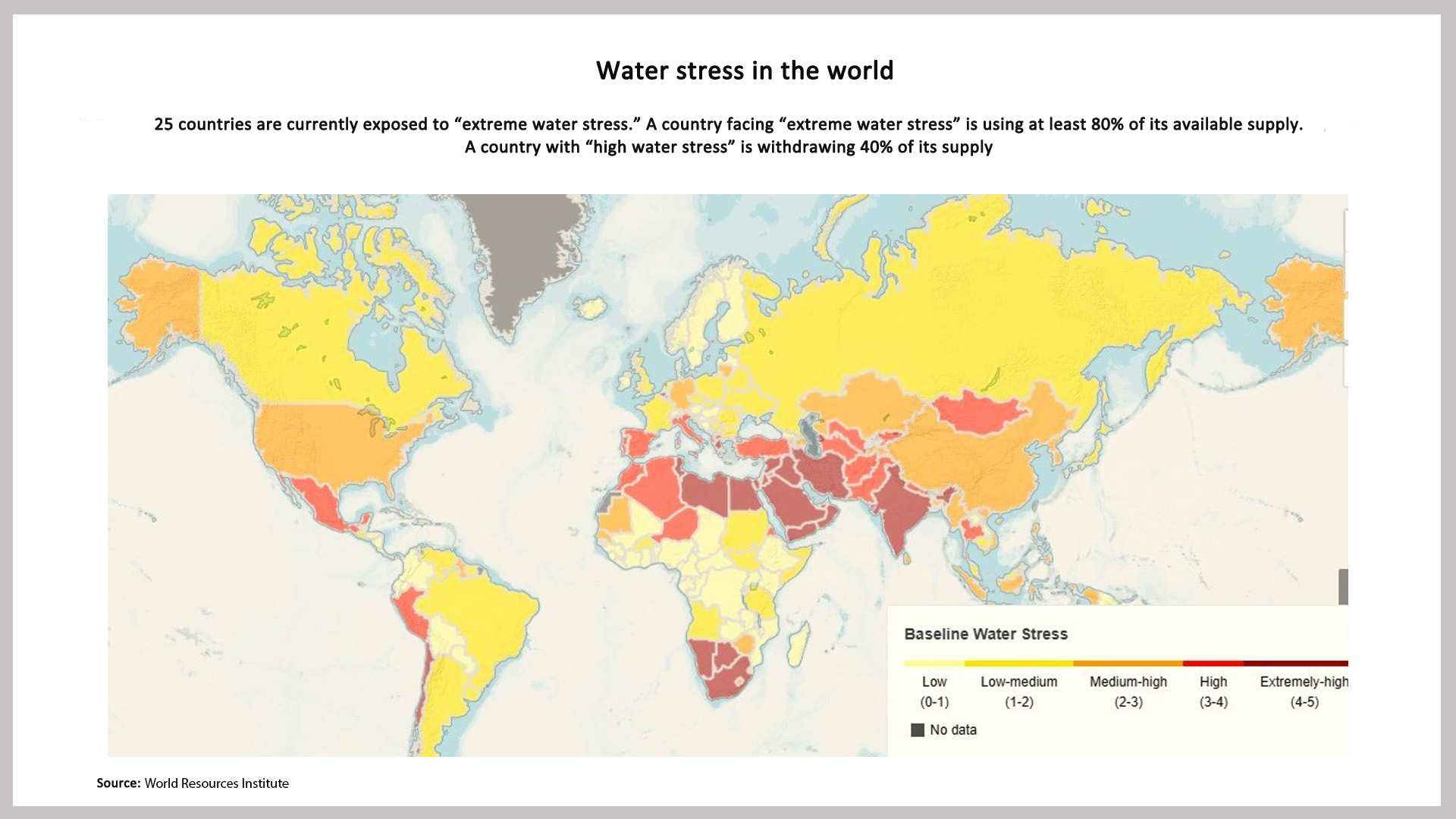

Forced migration, social tensions, and military conflicts caused by the water deficit are making this situation even worse. This is not a possible future scenario, but something that is already happening now. From 1970 to 2000, there was a 10% increase in global migration related to water shortages. According to a 2024 report by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2.2 billion people lacked access to safely managed drinking water at that time. Since 2022, approximately half of the world’s population has experienced severe water scarcity for at least part of the year, and a quarter has faced “extremely high” levels of water stress.

In this context, the journal Frontiers in Water published a dossier entitled “Emerging Water Contaminants in Developing Countries: Detection, Monitoring, and Impact of Xenobiotics”, which brings together five articles on the subject.

Geonildo Rodrigo Disner, a researcher at the Butantan Institute in São Paulo, Brazil, and a member of the Center for Toxins, Immune Response and Cell Signaling (CeTICS) – a FAPESP Research, Innovation and Dissemination Center (RIDC) – was co-editor and lead author of the editorial presenting the dossier.

“In addition to conventional contaminants, such as fecal coliforms, the presence of which is linked to low levels of sewage treatment, the freshwater in developing countries is increasingly being impacted by a new category of pollutants: emerging contaminants. These include agricultural pesticides, fuel additives, plasticizers or non-stick materials, medicines [such as antibiotics, painkillers, and hormones], hygiene products, and cosmetics,” says Disner.

Although they are not necessarily new, these compounds have been detected in concentrations and environments that were previously unrecorded, generating growing concern. This is the case with the herbicides diuron (used mainly on sugarcane and cotton crops), glyphosate (used mainly on soybean and corn crops), atrazine (used mainly on corn and sorghum crops), and 2,4-D (used to control broadleaf plants on pastures and crops).

“Because they aren’t removed by conventional water treatment methods, these pollutants accumulate in aquatic ecosystems and can cause toxic effects, even at extremely low concentrations. Many act as endocrine disruptors, impacting the reproduction and development of organisms – effects that can extend to human health. Exposure is generally chronic, continuous, and silent. And many of these compounds bioaccumulate along the food chain, further increasing the health risks,” says Disner.

The researcher points out that everything ultimately ends up in water. Water is the ultimate repository for most pollutants, including those released into the soil or air. In addition, water transports contaminants even to regions where they have never been used.

“Despite the risks, most emerging contaminants are still not regularly monitored or regulated by specific legislation. In general, treatment systems only remove coarse materials, such as suspended particles, part of the organic matter, and microorganisms. Even in the city of São Paulo, where we have a relatively more developed structure, all 27 pesticides tested were detected by the Water Quality Surveillance Information System [SISAGUA] in the monitored water. We live in a region with enormous pressure on water resources, and the treatment we have is still limited,” emphasizes Disner.

Faced with this situation, the articles in the dossier explore the challenges and recent advances in identifying, monitoring, and assessing the impact of emerging contaminants in low- and middle-income countries. One paper, written by Sri Lankan researchers, investigates the presence of heavy metals in groundwater and locally grown rice, linking exposure to a high incidence of chronic kidney disease. Another study from Bangladesh analyzed the quality of commercially sold bottled water, revealing contamination by arsenic and pathogenic microorganisms. A study from Brazil, conducted by researchers from São Paulo State University (UNESP), evaluates the toxic effects of diuron and its metabolites on zebrafish, an animal model used in ecotoxicological studies.

In addition to contaminants, the researcher highlights a broader structural issue: unequal access to water and the already visible effects of climate change. “Major floods, as we recently saw in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, compromise the entire structure for collecting and distributing drinking water. On the other hand, there are regions that are facing severe droughts. Between 2002 and 2021, droughts affected more than 1.4 billion people,” he says.

The dispute over water is already a reality in some parts of the world, and it is likely to intensify in the coming decades. According to a UNESCO report, approximately 40% of the world’s population lives in transboundary river and lake basins, but only one-fifth of countries have transboundary agreements to jointly manage these resources in an equitable manner. Many transboundary basins are located in regions characterized by current or historical international tensions.

“Water is becoming a geostrategic resource. And the privatization of water sources could transform this asset into a currency of control and power. We’re used to talking about the dispute over oil, but the dispute over water could be even fiercer. Water needs to be treated as a right. And it’s not just about access, but also about quality. Guaranteeing quality drinking water for the population is a duty of the State,” emphasizes Disner.

The authors of the dossier emphasize that preventing pollutants from entering aquatic ecosystems is essential and that this could be achieved through source prevention, the precautionary principle, and the remediation of contaminated areas. They also advocate creating regulatory frameworks and monitoring programs specifically aimed at emerging contaminants, with the aim of protecting human and environmental health, thus contributing to achieving the United Nations’ (UN) global sustainable development goals.

Disner’s participation was supported by FAPESP through a postdoctoral scholarship awarded to the researcher.

The editorial on the research topic “Emerging Water Contaminants in Developing Countries: Detection, Monitoring, and Impact of Xenobiotics” is available at: www.frontiersin.org/journals/water/articles/10.3389/frwa.2025.1584752/full.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.