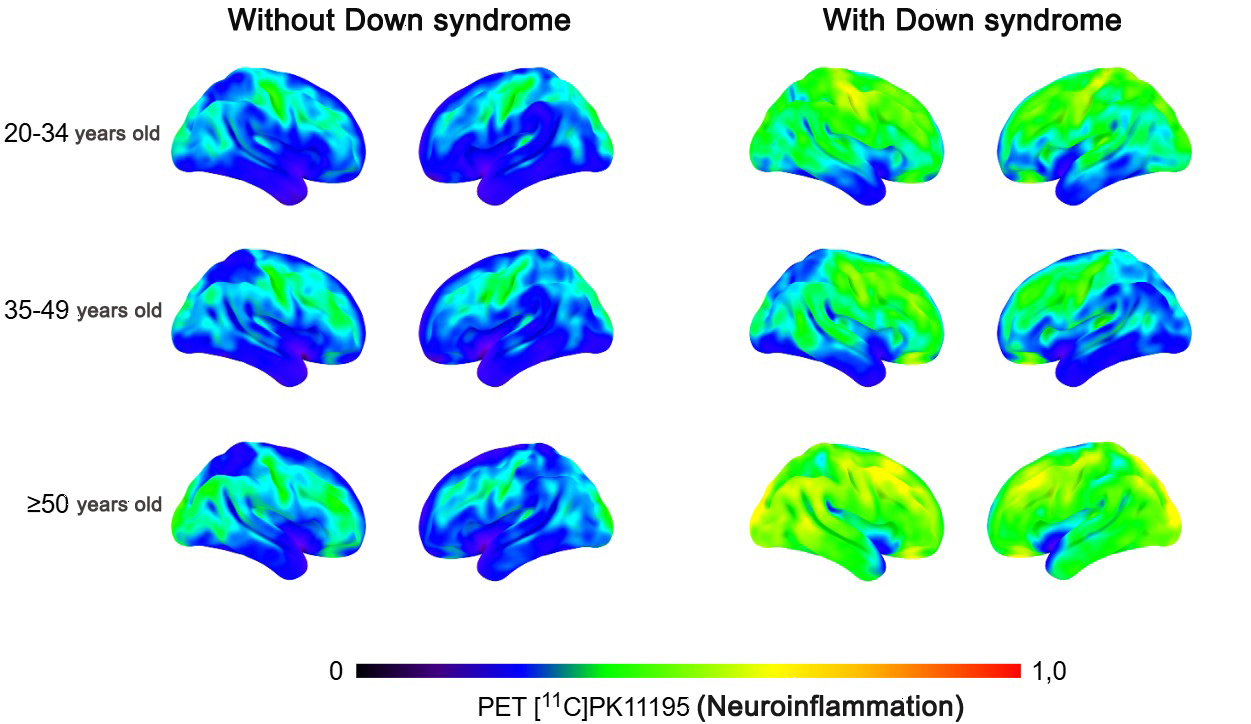

The image shows inflammation mapped in the brains of people with and without Down syndrome in different age groups (credit: Daniele de Paula Faria)

Researchers at the University of São Paulo identify a new factor that explains the high prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in older people with Down syndrome. The discovery paves the way for disease prevention strategies in this population.

Researchers at the University of São Paulo identify a new factor that explains the high prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in older people with Down syndrome. The discovery paves the way for disease prevention strategies in this population.

The image shows inflammation mapped in the brains of people with and without Down syndrome in different age groups (credit: Daniele de Paula Faria)

By Maria Fernanda Ziegler | Agência FAPESP – Down syndrome is associated with accelerated aging. It is estimated that up to 90% of individuals with the condition develop Alzheimer’s disease before the age of 70. A study by researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil identified high levels of neuroinflammation in young individuals with Down syndrome, an additional factor explaining the high prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in older people with the condition. The discovery paves the way for strategies to prevent and monitor the disease.

The study, which was published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia and was supported by FAPESP, is the first to map the patterns of neuroinflammation in people with Down syndrome using nuclear medicine techniques.

The researchers also discovered an important marker of Alzheimer’s disease: beta-amyloid plaque. This plaque is formed by fragments of amyloid peptide that are deposited between neurons, causing inflammation and disrupting neural communication.

“It was already known that the aging process in this population occurs more rapidly when compared to people without the syndrome, with Alzheimer’s disease already manifesting in people in their 40s, for example. It was also known that the risk of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in people with Down syndrome due to a genetic issue: the amyloid precursor protein [APP] gene is located on chromosome 21, which is tripled in Down syndrome, causing these individuals to produce more beta-amyloid – a characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease,” explains Daniele de Paula Faria, a researcher at the Nuclear Medicine Laboratory (LIM43) of the Hospital das Clínicas (HC), the hospital complex administered by the USP Medical School (FM).

What the study reveals for the first time is that neuroinflammation also manifests early, as early as age 20, and may directly contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease. “In the study, we identified a very clear relationship: the more neuroinflammation, the more beta-amyloid plaque deposition. This allows us to think of this process as a possible therapeutic target,” says Faria.

How the study was conducted

The study compared neuroinflammation patterns in 29 individuals with Down syndrome and 35 individuals without the condition. Participants were between 20 and 50 years old. Neuroinflammation was monitored using positron emission tomography (PET) with specific radiopharmaceuticals. This technique allows for the visualization of beta-amyloid plaque formation and inflammatory processes in the living brain in real time.

The results revealed increased neuroinflammation in the frontal, temporal, occipital, and limbic regions of the brains of individuals with Down syndrome, even among those aged 20 to 34. These results suggest that the neuroinflammation process may begin before beta-amyloid plaque formation. The correlation between inflammatory load and beta-amyloid accumulation was especially evident in adults over 50.

In addition to human analyses, the researchers monitored the progression of neuroinflammation in genetically modified mice with a condition similar to Down syndrome over two years. “With specific equipment for small animals, we were able to monitor the entire evolution of the disease. The data from the mice, combined with that from humans, offer valuable insights into the aging of people with Down syndrome,” says Faria.

Biphasic process

The neuroinflammation process observed in people with Down syndrome appears to follow a biphasic pattern. Microglia, the brain’s defense cells, act protectively by combating changes caused by the syndrome. However, over time, this response becomes pro-inflammatory, which can potentially aggravate neuronal damage. “It’s as if the brain tries to protect itself, but ends up contributing to the problem,” the researcher explains.

While there is still no cure or single defined cause for Alzheimer’s disease, this study sheds light on the relationship between neuroinflammation and plaque deposition in people with Down syndrome.

“Our study reinforces the hypothesis that neuroinflammation precedes beta-amyloid plaques in the Down syndrome population. This paves the way for the development of therapies that can slow or block this inflammatory process and thereby delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease,” says the scientist.

In addition to revealing a new early marker of the disease, the study presents an imaging tool capable of monitoring neuroinflammation in real time. “We’ve shown that it’s possible to detect inflammation in living patients, which allows us to monitor the effectiveness of treatments. This technology also opens the door to including people with Down syndrome in clinical studies on Alzheimer’s disease. This is a very important population because they have different patterns of disease development than the general population. Only then can we offer effective and personalized treatments,” Faria concludes.

The article "Neuroinflammation and amyloid load in different age groups of individuals with Down syndrome: A PET imaging study" can be read at alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/alz.70449.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.