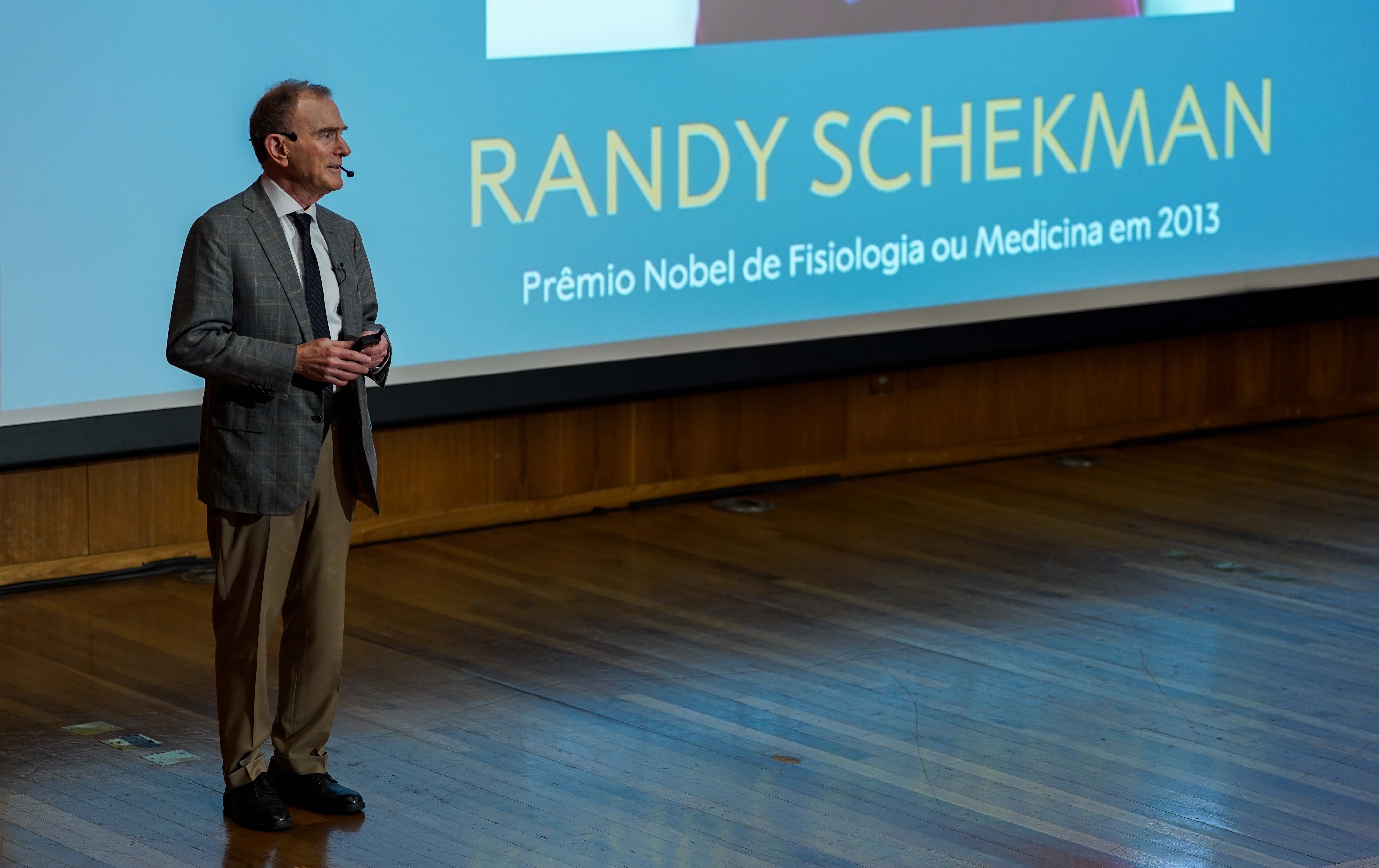

Schekman’s visit to São Paulo was organized with the support of FAPESP and USP as part of the Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative (photo: Daniel Antônio/Agência FAPESP)

The assessment was made by biologist Randy Schekman, winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Medicine, in conversation with students after a lecture at the University of São Paulo on November 25th.

The assessment was made by biologist Randy Schekman, winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Medicine, in conversation with students after a lecture at the University of São Paulo on November 25th.

Schekman’s visit to São Paulo was organized with the support of FAPESP and USP as part of the Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative (photo: Daniel Antônio/Agência FAPESP)

By Karina Toledo | Agência FAPESP – “The panorama of biomedical sciences today is much different and broader than when I started my career 50 years ago. There are incredible tools, much better than the primitive ones I had. Technology has advanced so fast that it’s hard to keep up. But the downside, which I spend a lot of time worrying about, is scientific production. It’s not as effective as it used to be,” said American biologist Randy Schekman, a researcher at the University of California at Berkeley (United States), in a conversation with students after a lecture in the city of São Paulo (Brazil), presented at the University of São Paulo (USP) on November 25th.

For the scientist, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2013, the phenomenon is linked to the proliferation of scientific journals that are driven by commercial goals and “interested in making a lot of money.” “This has a toxic influence on academia. In the past, we used to evaluate scientific production by reading the articles. Now, we look at where the article was published or at this ridiculous number called the impact factor,” he said.

Schekman is not new to criticizing the academic community’s dependence on so-called “high profile journals.” On December 9th, 2013, the day before he was awarded the Nobel Prize, he published an article in the British newspaper The Guardian announcing that from that day on his laboratory would boycott journals such as Nature, Science and Cell. “I’ve published in major journals, including articles that won me a Nobel Prize. But no more. Now my lab is committed to avoiding luxury journals, and I encourage others to do the same,” he announced at the time.

In his assessment, the pressure to publish in “luxury” journals has encouraged researchers to do their work quickly and poorly (to cut corners) and to pursue fashionable areas of science instead of doing really important work. And the problem has been exacerbated by the fact that the editors of these journals are not active scientists, but professional editors – almost always with an academic background – who tend to favor studies with a greater chance of having an impact.

When asked what he would do if he became editor-in-chief of one of these journals, Schekman said: “I would fire all the professional editors. They’re one of the reasons why the cost of publishing a scientific article is so high.”

The researcher also expressed concern about increasing the length of time it takes academics to complete their training and get a job. “I became a professor at the age of 27. Most of my contemporaries were employed before the age of 30. It’s a time of life when you have more freedom to be creative. I don’t think I could’ve done what I did if I’d started ten years older, because of family responsibilities.”

Schekman says it took him only four years to complete his Ph.D., and he was a postdoctoral fellow for another two years. “In my day, you could get a good post-doc position with just one published paper. Today the expectation in terms of number of publications is much higher. What’s more, some people now do several post-docs, and that slows things down to the point where you’re almost 40 by the time you get a job. If you take more than ten years to graduate, you’re not going to get a good job,” he said.

Schekman with students after a lecture at USP (photo: Daniel Antônio/Agência FAPESP)

Multifaceted disease

Schekman’s visit to São Paulo was organized with the support of FAPESP and USP as part of the Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative (NPII), a partnership between the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca and Nobel Media that takes laureates to universities and research centers around the world to inspire young scientists.

At the event, the researcher presented the studies on yeast that led to the discovery of a set of genes that are important for the transportation of vesicles from the intracellular to the extracellular environment. It is through these tiny bubbles – loaded with chemical substances such as enzymes, hormones and neurotransmitters – that cells communicate with each other and coordinate all the important processes in an organism.

“When the human genome was unraveled, we discovered that the same key proteins that we’d identified in yeast were present in our organism. It was a mechanism that had been conserved throughout evolution,” he said.

His findings laid the foundations for understanding diseases related to dysfunctional vesicular trafficking, including diabetes. For this contribution, Schekman was nominated for the Nobel Prize along with James Rothman (Yale University) and Thomas Südhof (Stanford University).

In 2017, however, the death of his wife, who had suffered from Parkinson’s for 20 years, led him to make a drastic career change. With the financial support of Sergey Brin – one of the founders of Google and a carrier of one of the most common mutations that lead to Parkinson’s – and the foundation set up by the actor Michael J. Fox, Schekman began researching the molecular basis of this neurodegenerative disease, whose incidence in the world is increasing even faster than Alzheimer’s. According to data presented in the lecture, there were 2 million cases worldwide in 1990. By 2040, 17.5 million people are expected to be affected, half of them in China alone.

“The disease was described 200 years ago, and so far nothing has been done to prevent its progression. There are drugs that can alleviate the symptoms, but they don’t stop the degenerative process that inevitably leads to death,” he said.

According to Schekman, Parkinson’s, like cancer, is not just one disease. There are several. All cases are linked to the death of so-called dopaminergic neurons (producers of the neurotransmitter dopamine), which in turn is associated with the growth of aggregates of the protein alpha-synuclein on nerve cells. However, the factors that cause the molecules to aggregate or that make neurons more susceptible to this threat vary. Only a small number of associated genetic mutations have been identified, and most cases are considered sporadic.

As leader of the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (Asap) initiative, which brings together 35 research groups from 14 countries, Schekman is working to understand at the molecular level what causes dopamine neurons to die. The goal is to find targets that can guide the development of drugs that are more effective at stopping the process.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.