A project conducted by Brazilian, Dutch and British researchers focuses on interdependencies linking three critical variables: food, water and energy (image: release)

A project conducted by Brazilian, Dutch and British researchers focuses on interdependencies linking three critical variables: food, water and energy.

A project conducted by Brazilian, Dutch and British researchers focuses on interdependencies linking three critical variables: food, water and energy.

A project conducted by Brazilian, Dutch and British researchers focuses on interdependencies linking three critical variables: food, water and energy (image: release)

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – In a world in which resource scarcity is increasingly common, the food-water-energy nexus is a critical bottleneck for people living on the periphery of cities in poor or developing countries.

An international collaboration involving researchers from Brazil, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom is studying this nexus in three midsize cities: Guarulhos in Greater São Paulo, Brazil’s largest metropolitan area; Kampala, the capital of Uganda; and Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria.

A nexus is a cluster of issues that are interconnected in such a way that interventions focusing on one are likely to have a negative impact on others. In this instance, the use of the term reflects the perception that food, water and energy are so interdependent that increasing one entails depleting the others and affects all the production and supply chains involved.

“If more water is made available to large numbers of people, this will have a negative impact on food and energy production. The same applies if each of the other two variables is emphasized. These tradeoffs mean scarcity is much more complex than the conventional notion implies,” said Leandro Luiz Giatti, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Public Health School (FSP-USP) and principal investigator for the Thematic Project “Resilience and vulnerability at the urban nexus of food, water, energy and the environment (ResNexus)”.

Formatted in response to a call for proposals focusing on urban sustainability issued by FAPESP in partnership with the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), ResNexus is a collaboration by researchers affiliated with USP, Wageningen University (Netherlands) and the University of Sussex (United Kingdom). In Brazil, a study pertaining to the thematic project is also being conducted in Guarulhos by Carolina Monteiro de Carvalho, a postdoctoral fellow at FSP-USP, with Giatti as supervisor and a scholarship from FAPESP.

Global scarcity is a fact, but of course, there are degrees of severity according to the country or region. Brazil’s abundance of water has not prevented the occurrence of major regional shortages in recent years. Moreover, its agricultural model based on intensive production and exporting of commodities is water and energy intensive.

With regard to the fact that the collaboration focuses on three cities, Giatti notes that the world population is increasingly concentrated in cities and urban populations tend to consume more.

“So, cities drive the dynamics of demand for food, water and energy. However, the interdependencies and tradeoffs aren’t strictly confined to urban territories. Today, for example, much of São Paulo City’s water supply comes from as far away as Minas Gerais, a neighboring state,” Giatti told Agência FAPESP.

Albeit very different in many ways, Guarulhos, Kampala and Sofia have several problems in common, and all three have a similar population in the range of 1 million-1.5 million inhabitants.

“The three studies use an ethnographic technique called shadowing, a form of nonparticipant observation in which overlapping qualitative investigations are conducted to understand social practices in a context of vulnerability. The underlying assumption is that populations use the means at their disposal, their knowledge and know-how, to develop various social practices to deal with scarcity. This is a key element of all three studies,” Giatti said.

“In Kampala, for example, the informal settlements or slums that form a mosaic throughout the city are territories where there’s practically no state presence. In contrast, although the favelas of metropolitan São Paulo are enormously deprived, there are basic health units (UBSs) or access to such units and schools or access to schools, and most have piped water supply systems.

“Nothing of the kind exists in Kampala. So an example of social practice there relates to cooking. People mainly use charcoal, firewood or wood chips for cooking. These materials are fairly easy to obtain but expensive. As a result, they’ve stopped eating beans because of the large amount of water and energy needed to cook beans. Their main staple instead is matooke, which is steamed mashed plantain with groundnut sauce. It doesn’t take long to prepare and requires relatively little energy.”

Based on ethnographic investigations of this kind, the project identifies not only the solutions found by communities to survive amid scarcity but also their aspirations, proposals and future vision. The vast gap between the social practices of people living in conditions of vulnerability and the decisions of public policymakers is one of its main concerns.

“This gap is very striking in all three cities. We recently met with a researcher from Bulgaria who’s working on an upgrade of Sofia’s master plan. She showed us that while the city inherited good infrastructure from the socialist regime that ruled Bulgaria until 1989, citizens have a hard time interacting with planners because of the persistence of authoritarian practices despite the advent of a more democratic regime and also because of a lack of public information from the government,” Giatti said.

“The best we’ve managed so far to bridge this gap are events we call Vision Building Workshops, where people who live in vulnerable areas meet with local leaders, academics and public administrators.”

Maps and questionnaires

In a neighborhood of Guarulhos the collaboration is studying, the construction of channels for such a dialogue was one of the results of Carolina Monteiro de Carvalho’s postdoctoral research.

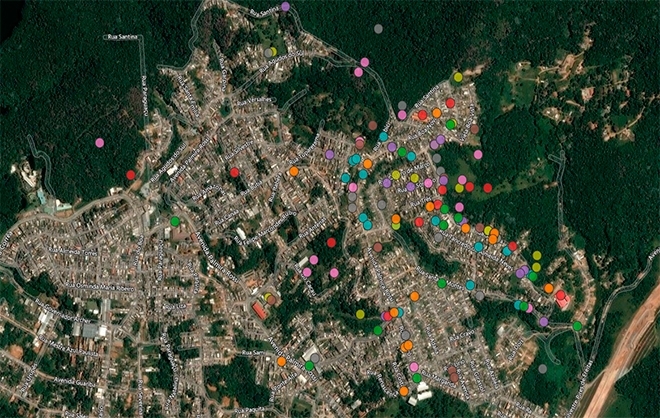

“My project, which I conducted as a ramification of ResNexus, focused on the construction of a participatory geographic information system [known as SIGP, after the Portuguese abbreviation]. The system is designed to produce a survey of the social and environmental problems perceived by the inhabitants of the Novo Recreio neighborhood. We started to build it with youngsters who go to the local high school. We gave them a three-month course to help them learn to use the system locally,” Carvalho said.

“The next stage, on which I’m currently working, is the production of a questionnaire based on the Finnish participatory mapping tool Maptionnaire, to be answered by citizens living in all areas of Guarulhos. Their feedback will reflect their needs and desires for a better future and the construction of a socio-environmental system with more justice and equity.”

Novo Recreio is a new part of the Recreio São Jorge district where some 4,500 families live at the foot of the Serra da Cantareira hills. The rugged terrain makes it an environmentally hazardous area that has improperly sited garbage dumps and is subject to landslides and flooding.

Urban mobility is a major problem for the neighborhood’s inhabitants because of the unpaved hillsides, which buses cannot climb on rainy days, and water shortages are chronic.

“We began our study with the support of Clube de Mães, an NGO founded by Cida, a resident who has been fighting for improvements for the Novo Recreio community for many years,” Carvalho said. “This NGO supported our entry into the neighborhood, as did the local health center, which is managed by Fabiana Bueno, and 22 school students aged 14-17 who were taking courses offered by Clube de Mães also joined in. We held weekly hour-long meetings for three months. The feedback they gave us served as a basis for our survey of the area’s social and environmental problems.”

Several tools were deployed to obtain this feedback. One was a “Talking Map” drawn on paper by participants to pinpoint social or environmental problems in the neighborhood. Another was a “Manual PGIS”, produced by locating desirable features of an area on a sheet of tracing paper overlaid on a map printed from Google Maps.

“These were only some of the tools we used. When the survey was complete, I used Maptionnaire to have the students plan the infrastructure they wanted to see in the neighborhood as part of their future vision,” Carvalho explained.

Using the information gathered at these meetings, the students produced a map diagnosing the neighborhood’s social and environmental problems, as well as a planning map with the aid of Maptionnaire.

“Now we have a picture of the situation in the area and also of the changes these young people want to make,” Carvalho said. “The second stage of the project, which is under way, consists of thematic meetings with the community. In addition to the students, we invite other residents of the area, including older people, whose views we want to include, of course. Our aim is to develop proposals for strategies to be implemented in the future. We already have the support of Clube de Mães, the local health center, and the city’s health department.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.