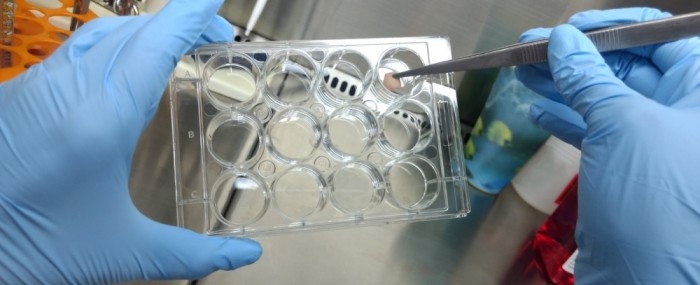

Infrared radiation penetrates deeper than UV, creating oxidative stress in the underlying layers and damaging DNA (photo: Kosmoscience)

Goal is to understand structural alterations undergone by skin exposed to infrared radiation.

Goal is to understand structural alterations undergone by skin exposed to infrared radiation.

Infrared radiation penetrates deeper than UV, creating oxidative stress in the underlying layers and damaging DNA (photo: Kosmoscience)

By Suzel Tunes | FAPESP Research for Innovation – The effects of ultraviolet radiation (UV) on the skin are well known to science and the cosmetic industry. A wide array of products on the market act as chemical barriers against UV rays from the Sun, preventing skin cancer and premature aging. Scientists are now endeavoring to achieve a better understanding of the structural alterations undergone by skin exposed to near-infrared radiation (IR-A), which is felt as heat and comes not only from the Sun but also from household appliances such as clothes irons and hair dryers.

Kosmoscience, a Brazilian company that specializes in clinical trials of cosmetics, is developing an alternative methodology to animal experiments to study the damage caused by IR-A using fragments of human skin from elective plastic surgery. Its research is supported by FAPESP’s Innovative Research in Small Business Program (PIPE) and has completed Phase 1, which is concerned with technical feasibility.

According to the principal investigator, pharmacologist Samara Eberlin, Kosmoscience’s aim in evaluating the harmful effects of IR-A on fragments of human skin is to validate the use of this alternative material in tests of the efficacy of protective products.

She explains that since the advent of the 3 Rs (Replace, Refine, Reduce) to make experimental techniques more humane and ethical, with fewer animals involved, the safety and efficacy of cosmetic products has been assessed in vitro (cultured cells in the lab) and through clinical trials in humans. “However, the damage done by an aggressive agent or the benefits of a treatment observed in cell culture experiments can’t always be extrapolated directly to real conditions of use,” she says. In light of this constraint, trials using ex vivo skin have become a valuable tool to fill the gap left by avoidance of animal testing.

The skin fragments used by Kosmoscience in its research are plastic surgery waste obtained with the consent of the patients concerned and the approval of the relevant Research Ethics Committee. There is no shortage of this material. Brazil ranks second worldwide in plastic surgery, according to data published by the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS) in June 2017. “Material normally thrown away is donated for research purposes,” Eberlin says.

No lab test can completely simulate real-world conditions, she acknowledges, but skin fragments recently obtained from plastic surgery are a satisfactory model. “Once the skin is removed, the tissue remains viable for seven to ten days in culture. The main alterations relating to aging, pigmentation and inflammatory response, among others, can be measured using this model,” she stresses.

Eberlin and biologists Michelle Sabrina da Silva and Gustavo Facchini have so far succeeded in obtaining results that demonstrate the damage IR-A can do to the skin, including acceleration of aging processes, cell death, and weakening of the physiological mechanisms involved in tissue repair.

“The findings are preliminary, but they indicate that infrared radiation produces alterations in normal skin metabolism and can cause not just aesthetic harm but even malignant malformation,” Eberlin says. IR-A penetrates deeper than UV, she explains: it creates oxidative stress in the underlying layers and can damage DNA. For this reason, some sunscreens already include anti-oxidants in their formulation. However, it is still necessary to obtain more data on IR-A’s action mechanism and the ideal concentration of antioxidants.

A number of technical difficulties had to be addressed during the first phase of the research project, leading to delays. “We had to adapt the protocol and use certain reagents not originally planned for,” she says. Nevertheless, all the goals proposed for the project were achieved.

In Phase 1, the tests performed using the ex vivo skin model enabled Kosmoscience’s researchers to establish the harmful effects of IR-A more precisely at the cellular level. “The idea was to obtain a broad picture of the alterations caused by infrared radiation,” Eberlin says. “We had previously looked at certain markers of aging in IR-stressed systems, but we needed to understand this stress more fully.” In the next phase, these results will be used to develop biomarkers, which the firm will offer the cosmetics industry, extending the range of methodologies available for the study of new formulations.

Pursuing innovation

Kosmoscience has operated in the pharmaceutical and cosmetics markets for 14 years. It began as a spinoff from São Paulo State University’s Interdisciplinary Electrochemistry & Ceramics Laboratory (LIEC-UNESP) in Araraquara, Brazil. LIEC is headed by Professor Elson Longo and attached to the Center for Research and Development of Functional Materials (CDFM), one of the Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs) funded by FAPESP.

Chemist Adriano Pinheiro, founder of Kosmoscience, was a member of Prof. Longo’s research group and mentored by Longo when the firm was established in 2003. Today, Kosmoscience has a staff of more than 50 people and operates internationally by exporting technical services and know-how to over 30 countries.

It has built a strong market position but maintains a fruitful dialogue with universities. Pharmacologist Eberlin sees participation in research projects as enabling staff to exchange knowledge with professionals in other fields. This is what is happening now, for example, with the use of computational tools to analyze the data obtained in laboratory experiments.

“Bioinformatics requires a dialogue among pharmacologists, biologists, chemical engineers, and even mathematicians,” she says.

Biologists Silva and Facchini agree: “It brings all these fields together,” they say.

“And besides financial support, having a project approved by meeting FAPESP’s scientific standards is hugely important to the firm’s corporate image,” Eberlin adds.

Company: Kosmoscience

Site: kosmoscience.com

Address: Rua Sandoval Meirelles 72, Vila João Jorge, Campinas, CEP 13.041-315, SP, Brazil

Tels: +55 19 3829 3482 and +55 19 3829 0841

Contact: ks@kosmoscience.com

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.