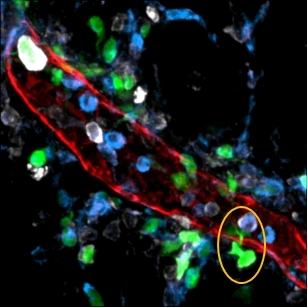

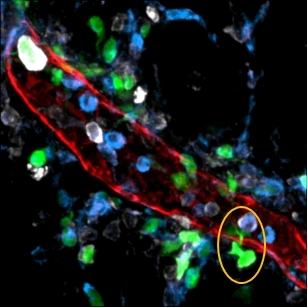

Image illustrating dendritic cells (green) escaping into mesenteric adipose tissue through the wall of a lymphatic vessel (red) (image: release)

The hypothesis was investigated at the University of São Paulo by Denise Morais da Fonseca, a prizewinner of the 11th edition of "Awards For Women in Science".

The hypothesis was investigated at the University of São Paulo by Denise Morais da Fonseca, a prizewinner of the 11th edition of "Awards For Women in Science".

Image illustrating dendritic cells (green) escaping into mesenteric adipose tissue through the wall of a lymphatic vessel (red) (image: release)

By Karina Toledo | Agência FAPESP – Could a single episode of intestinal infection make a person prone to developing cardiovascular disorders, obesity, diabetes or food intolerances and inflammatory bowel disease?

This troubling hypothesis is being investigated with FAPESP’s support at the University of São Paulo’s Biomedical Science Institute (ICB-USP) in Brazil. The principal investigator is Denise Morais da Fonseca, one of seven prizewinners at the eleventh edition of the “Awards For Women in Science”, awarded by L’Oréal Brazil in partnership with the United Nations Organization for Education, Science & Culture (UNESCO) and the Brazilian Academy of Sciences (ABC).

“Experiments with mice suggest that infection can leave behind as a sequela a sort of immunological scar – a permanent change in the communication pathways between the intestine and the immune system,” Fonseca said. “We are now investigating how this relates to the development of metabolic diseases.”

This line of research began during Fonseca’s postdoctoral studies, including a research internship in the US with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded by a scholarship from FAPESP.

At that time, Yasmine Belkaid’s group at NIH infected mice with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, a bacterium that causes acute diarrhea and fever in both mice and humans.

“This kind of gastrointestinal infection is common,” Fonseca said. “In most cases it is benign and self-limiting, so infected individuals tend not to seek long-term medical care. However, it was unknown whether this resulted in sequelae in the organism.”

After tracking the animals’ recovery for two years (laboratory mice live three years on average), the researchers concluded that there may indeed be permanent consequences.

Their findings were published in an article in Cell, which inspired commentaries in Nature, Nature Reviews Immunology and Science, among other journals.

Two weeks after being infected, all the mice had excreted the bacteria, but almost 80% showed remodeling of the mesentery, a fold of membrane that attaches the intestine to the abdominal wall and holds it in place.

“Inside the mesentery there are a number of immune system structures, such as lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels, which act as conduits for the cells that provide immune surveillance of the intestine and identify tissue alterations. These structures remain damaged after the infection and do not return to normal without some kind of intervention,” Fonseca said.

Damage to the lymphatic vessels in the mesentery leads to increased permeability and hence leakage, she added, so that lipids from ingested food and immune cells fail to reach their proper destinations.

Fonseca discovered this when she noticed that murine lymph nodes were lacking in a specific population of dendritic cells, a type of defense cell that is responsible for presenting antigens to the immune system so that they are recognized and, if necessary, an adaptive immune response is initiated through lymphocyte activation.

“Only one population was missing, and it was precisely the one that should migrate from the intestine to the lymph nodes in order to induce an adaptive immune response,” Fonseca said. “We looked everywhere and found these dendritic cells in the mesenteric adipose tissue, which is traversed by lymphatic vessels. Therefore, they were escaping from the vessels into that tissue.”

Subsequent tests showed that as a result of this leakage, the immune system appeared to have lost the ability to distinguish between benign antigens such as those derived from food and real threats such as pathogenic bacteria. Inflammatory reactions in the intestine were exacerbated, and the animals’ mesenteric adipose tissue eventually exhibited chronic inflammation.

“Evidence in the scientific literature links chronic inflammation in mesenteric adipose tissue to the development of diabetes, insulin resistance and obesity. These mice did indeed become diabetic and insulin resistant,” Fonseca said.

According to her hypothesis, the remodeling induced by infection sufficiently altered the permeability of the intestinal wall to allow microbiotic bacteria to escape into other tissues. Although these bacteria are beneficial while inside the intestine, outside their usual habitat they help to sustain inflammation of mesenteric adipose tissue, even after the infection that caused the remodeling has ended. Mesenteric adipose tissue inflammation, in turn, is responsible for maintaining alterations of the mesentery, thus creating a vicious circle.

To test their hypothesis, the researchers gave some of the mice antibiotics to eliminate their entire intestinal microbiota. As expected, this group did not develop mesenteric adipose tissue inflammation after initial infection with Y. pseudotuberculosis.

“This study does not present a therapeutic proposal for humans. Its purpose is simply proof of concept,” Fonseca said.

The group is currently investigating the hypothesis that leakage of dietary lipids into the peritoneal cavity due to increased lymphatic vessel permeability may be one of the key factors underlying the metabolic disorders observed in these cases.

“Dietary lipids are normally transported by lymphatic vessels to the vena cava, where they enter the bloodstream, reach the liver and are metabolized,” she explained. “When they leak into the peritoneal cavity, their circulation, distribution and metabolism are completely changed.”

The researchers’ preliminary results suggest that these lipids are deposited in unusual regions such as the pancreas and liver, as is the case in HIV/AIDS patients who develop lipodystrophy and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Prospects

In another series of experiments, the researchers infected one group of mice with Toxoplasma gondii, the protozoan that causes toxoplasmosis, and another with bacteria of the genus Citrobacter, which can cause several diseases including intestinal infection.

In the first case, they observed the same type of immunological scarring as that induced by infection with Y. pseudotuberculosis. In the second, there appeared to be no sequelae.

They also observed the occurrence of mesenteric remodeling in an animal model of colitis: intestinal inflammation induced by irritating chemical substances.

“Apparently not all pathogens induce this kind of remodeling, and the process does not occur in all individuals with gastrointestinal infections,” Fonseca said. “We do not yet understand what the determinants are, and this is something we intend to investigate.”

The group also plans to identify biomarkers that enable early detection of immunological scarring. “It could be some kind of blood lipid or a bacterial component or even an imaging method that can be used to evaluate lymphatic vessel integrity,” Fonseca said.

Early diagnosis and intervention would be crucial to avoid progression of the condition until metabolic disorders develop, she added. One possibility would be to test drugs that might block the action of immune system mediators associated with lymphatic vessel damage, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1).

“For example, we might test antibodies capable of blocking the cytokine TNF-α [tumor necrosis factor alpha] or IL-1. They already exist on the market and are used to treat colitis,” Fonseca said.

Awards

In addition to Fonseca, another prizewinner at this year’s “Awards For Women in Science” was Claudia Kimie Suemoto, a researcher at the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (FM-USP) whose work focuses on interactions among risk factors for cardiovascular disease, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

The other prizewinners were as follows: Ana Chies Santos and Adriana Neumann de Oliveira from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS); Gabriela Trevisan from the Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSC); Fernanda de Pinho Werneck from the National Amazon Research Institute (INPA); and Elisama Vieira Santos from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN).

Each prizewinner will receive R$ 50,000 in cash to fund further research. The awards ceremony will take place on October 20 at the Museum of Tomorrow (Museu do Amanhã) in Rio de Janeiro.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.