Study revisits the contributions of French anthropologists Pierre and Hélène Clastres on the Tupi-Guarani tribe, "a challenge for the dominant model of development"

Study revisits the contributions of French anthropologists Pierre and Hélène Clastres on the Tupi-Guarani tribe, "a challenge for the dominant model of development".

Study revisits the contributions of French anthropologists Pierre and Hélène Clastres on the Tupi-Guarani tribe, "a challenge for the dominant model of development".

Study revisits the contributions of French anthropologists Pierre and Hélène Clastres on the Tupi-Guarani tribe, "a challenge for the dominant model of development"

By José Tadeu Arantes

Agência FAPESP – Revisiting the thoughts of French anthropologists Pierre and Hélène Clastres is one of the pièces de résistance of Professor Renato Sztutman’s book, O Profeta e o Principal (The Prophet and the Principal). Professor Sztutman is an anthropologist at the University of São Paulo.

The seminal works of the Clastres have created division in anthropological thought and have had profound repercussions in philosophy, sociology and political practice. Between 2001 and 2005, under the supervision of Dominique Tilkin Gallois and with support from a FAPESP fellowship, Sztutman reevaluated the Clastres’s works in his doctoral thesis. Also funded by FAPESP, Sztutman’s recent book evaluates the theoretical material on the Tupi-Guarani tribe.

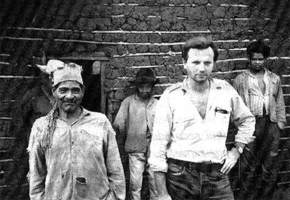

“The reflection on the Guarani was fundamental for Pierre Clastres [1934-1977] to formulate his concept of society against the state,” says Sztutman. “It is what we are seeing today, 35 years after the premature death of Clastres [who died at age 43 in a car accident] is precisely a reflection of this. Because they are structured as a society against [an organized] state, the Guarani became undesirable for society and for the hegemonic state.”

Sztutman points to several characteristics that would make the Guarani a challenge for the dominant development model: “They are people that live in regions that are being occupied by agribusiness; that cross national borders, transiting between Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina and Uruguay; that have a completely different relationship with the Earth; that despite being leaders and knowing how to organize politically for self-defense, resist centralization of policy and the figure of a central chief.”

According to Sztutman, Brazilian society has long turned a blind eye to crimes committed against the Guarani. “They were being decimated and no one cared,” he says. “Today, a significant portion of society finally reached the conclusion that giving populations the right to exist outside a hegemonic model is vital. We can no longer turn a blind eye. We have to position ourselves for the right of these societies to be what they are: against the state (and its developmentalist model), within a state.”

The Guarani live in many locations in southeastern and southern Brazil. In the city of São Paulo, which is not far from the central landmark Praça da Sé, there are three Guarani villages: two in Parelheiros and another near Pico do Jaraguá. However, because the villages occupy little space and the Guarani are always moving, contact with the surrounding society is limited. The Guarani have become practically invisible.

“In a text penned in the mid 1980s, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro (an anthropologist and professor at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro) [the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro] referred to them as an imperceptible people,” comments Sztutman. “When we think of Indians, we think of the Amazon or the past. But the Guarani are not in the Amazon, nor the past. They are right in front of our eyes. And we don’t see them.”

According to Sztutman, Pierre Clastres’s divisive book, A Sociedade contra o Estado (The Society against the state), has had repercussions in philosophy and the human sciences. Clastres interprets the absence of a state in indigenous societies not as a deficiency but as a rejection of the surrounding society, and indigenous societies often have efficient mechanisms that perform state functions.

According to Clastres, the classical European ideology is no longer an ineluctable model for interpreting the trajectory of the world’s peoples. Sztutman’s O Profeta e o Principal speaks to a movement of recovery and revision of the works of the Clastres.

“Particularly in the 1980s,” writes Sztutman, “anthropologists moved away from the Clastrean perspective because they sought a more empirical anthropology and Clastres was considered excessively philosophical: someone who worked with data in an imprecise manner and reached major conclusions based on little evidence.” Sztutman continues: “The fact is, at the time that [Clastres] wrote his books in the 1960s and 1970s, there were few ethnographic studies on Amazon peoples, including the Tupi language.

In the following decades, however, important studies were conducted. And mainly with the work of Viveiros de Castro, there began a reapproximation of ethnology and philosophy, but now with the possibility of discussing philosophical ideas based on a wealth of empirical data. And this created space for revisiting the Clastres, Pierre and Hélène.”

Sztutman, who is also a researcher at the Center for Amerindian Studies and the Anthropology Laboratory of Image and Sound, considers himself to be an heir of the new trend to recognize the contributions of not only Viveiros de Castro, but also Márcio Goldman and Tânia Stolze Lima of Rio de Janeiro, and Dominique Gallois and Beatriz Perrone-Moisés of São Paulo. In fact, Sztutman has frequently worked with Professors Gallois and Perrone-Moisés, who wrote the preface to his book.

“Although the Guarani are today the most populous indigenous people in South America, there are also many Tupi in the Amazon,” says Sztutman. “What prompted my interest in the old Tupi were the Amazon Tupi, not the Guarani.”

“My research work is based on the continuity of indigenous forms of political organization in the past to the present,” adds Sztutman. “Based on this continuity, I am attempting to identify the relationship of the two important figures: the chief or ‘principal’, linked to war, and the xamã or ‘prophet’ linked to the nonhuman world. They are two figures that are at once opposite and complementary.”

“It is in the alternation of these two forms of leadership that social life is constituted,” explains Sztutman. “But there is not total dualism, because you do not find pure forms of these figures. Every war chief is a little bit of a xamã; every xamã is little bit of warrior. They are a combination of principles. The prophet is a great xamã. Someone that goes beyond the narrow definition of xamanism, focused solely on cures and witchcraft, which gives him political meaning, leading migrations to the ‘land without malice.’”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.