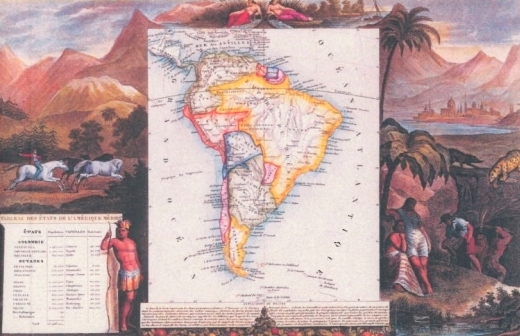

A new book investigates how the political experience of Spain's colonies in the Americas was elaborated by the leaders of the Brazilian independence process, inspiring concrete action (image: detail from the cover of A Independência do Brasil e a Experiência Hispano-Americana (1808-1822))

A new book investigates how the political experience of Spain's colonies in the Americas was elaborated by the leaders of the Brazilian independence process, inspiring concrete action.

A new book investigates how the political experience of Spain's colonies in the Americas was elaborated by the leaders of the Brazilian independence process, inspiring concrete action.

A new book investigates how the political experience of Spain's colonies in the Americas was elaborated by the leaders of the Brazilian independence process, inspiring concrete action (image: detail from the cover of A Independência do Brasil e a Experiência Hispano-Americana (1808-1822))

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – For many years, Brazilian independence was presented as a sort of counterpoint to the emancipation movements that took place in Spanish America. Many historians have argued that Spain’s colonies in the region won independence with violence, whereas Brazilian independence was bloodless and conserved both the positive and negative aspects of the Portuguese colonial heritage. A new book challenges this consensus.

A Independência do Brasil e a Experiência Hispano-Americana (1808-1822), written by João Paulo Pimenta, professor of history at the University of São Paulo (USP), was published in late 2015 with support from FAPESP.

“The book resulted from my doctoral thesis, ‘O Brasil e a América Espanhola, 1808-1822’, supervised by Professor István Jancsó (1938-2010) and was supported by FAPESP,” Pimenta told Agência FAPESP. “The book took more than ten years to publish. In the meantime, I updated the bibliography, included new sources and made a few minor corrections, but the central idea and all of its ramifications are unchanged.”

What is this central idea? “It’s that if many aspects of Brazilian independence were different, they were able to be different because the Brazilian process happened a bit later,” Pimenta said. “The gap of a few years explains the differences because the protagonists of Brazilian independence were able to learn from what happened in Spanish America. This learning curve was based on exchanges of information and the implementation of a border policy, which I set out to analyze.”

Pimenta examined three types of written material: articles and reports published in the press, diplomatic correspondence, and travelers’ accounts. In addition to Brazilian archives and documents available online, his research also took place in Spanish-speaking countries. “While completing my PhD, I spent three months in Buenos Aires and a month in Montevideo,” he said. “Since then, I’ve done stints as a visiting professor in Mexico, Spain, Chile, Uruguay and Ecuador. I was able to use this experience to reinforce my cross-border approach to the Brazilian process.”

The interest aroused in Brazil by news from Spanish America was an important factor in the independence process. “Public spaces in Portuguese America were steadily politicized from the end of the eighteenth century on. People who had always been indifferent to politics began taking an interest. With the arrival of the Portuguese Court in 1808, this interest was manifested mainly by the creation and circulation of newspapers, but also by rumor-mongering and a curiosity for new information. These phenomena spread more and more, involving various social groups. It wasn’t necessary for people to be able to read to participate. They could just listen and pass on rumors brought by merchant shippers, for example. The process was led by elite groups, but members of other classes also played key roles,” Pimenta said.

The Court, led first by Dom João (Prince Regent and then King of Portugal) and later by Dom Pedro as Emperor of Brazil, was evidently important to the reception and elaboration of information. Its ministers and secretaries read newspapers, ran informers, and had diplomatic representatives in several foreign cities. According to Pimenta, however, the flow of information was not confined to the Court. “Merchants and traders were also interested in what was going on in the rest of the world, especially Spanish America. They received and disseminated books, newspapers and rumors. Newspaper publishers and editors were even more active,” he said.

The Correio Braziliense, produced in London, England, by Hipólito José da Costa (1774-1823), was a major focus for Pimenta’s research. Circulating with repercussions in several of the world’s major cities, this periodical was published monthly with absolute regularity between 1808 and 1822, the period covered by Pimenta’s book between the Portuguese Court’s arrival in Brazil and Dom Pedro’s declaration of independence. Hipólito’s paper was critical of the Portuguese monarchy but from a reformist rather than a revolutionary standpoint. It backed independence only at the eleventh hour in 1822. According to Pimenta, its treatment of the Spanish Empire’s breakup was highly interesting and detailed.

Hipólito graduated in law, philosophy and mathematics from the University of Coimbra. He was sent on diplomatic missions to the US, Mexico and Great Britain. After being imprisoned in Lisbon, he escaped and eventually took refuge in London. He had become a freemason while in Philadelphia at the turn of the century, and freemasonry was as important as journalism to his story. Indeed, many freemasons played leading roles in the Brazilian independence process, including José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva and Joaquim Gonçalves Ledo, among others.

“Like various spaces of sociability at that time, freemasonry also elaborated Spanish America’s experience,” Pimenta said. “For example, Dom Pedro was initiated into freemasonry in August 1822 with the symbolic name Guatimozín, which was the Spanish chroniclers’ name for Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor. Many other masons took the names of Aztec or Inca chieftains, as well as more recent American personages. The idea was that America was emancipating itself from Europe and that some indigenous elements were positive. The people who led the Brazilian process were inspired by these elements, which they used to follow the example set by the rest of the continent.”

Historians who see a contrast between Brazilian independence and that of the Spanish colonies in the Americas have been influenced by the leaders of the Brazilian process, Pimenta added. They established the comparison in their own time, exalting the advantages of their own movement. “They stressed four points,” he said. “The first was what they saw as the peaceful nature of Brazilian independence, presented as an agreement among elite groups. The others were the preservation of the monarchy, territorial integrity and slavery. With a few secondary variations, these four topics structured practically the entire historiography of independence, defining the version that surpassed the boundaries of specialized literature to become common sense. This is the way the general public thinks of the independence process in Brazil.”

According to Pimenta, his book does not put forward a completely new interpretation. “That’s not my intention at all. These four characteristics did exist, but they were not alone. Reducing Brazilian independence to these four topics is a gross oversimplification in my view because what actually happened was a recreation of these elements rather than their simple preservation,” he said.

Knowledge and experience

Pimenta’s revisionism is basically a matter of emphasis, of putting the four elements mentioned into a broader interpretative context in which all the emancipatory movements of Iberian America are understood to be parts of one and the same process. “Historical experience doesn’t point to a disconnect between the independence of Portuguese America and the Spanish American processes: on the contrary, it points to a clear link. Despite the beliefs of the main protagonists, which defined the predominant view, the history of Brazil has never been isolated from the Latin American context,” he said.

The idea that the key actors in the Brazilian process elaborated on the Spanish American experience is central to the book. “In my view, knowledge and experience are key facets of any historical process,” Pimenta said. “So, when I researched in my source material, I tried not to confine my analysis simply to making an inventory of what was known. I also investigated how this knowledge was experienced by the different protagonists. In other words, how the information that came from Spanish America engendered concrete political action in Brazil. Knowledge often came after action, not necessarily before. For example, the need to resolve border problems was imposed by experience, but this experience required better knowledge of the neighboring territories, among which Rio de la Plata was the most important but not the only important one. It was a two-way street.”

A Spanish translation of A Independência do Brasil e a Experiência Hispano-Americana (1808-1822) is due to appear this year.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.