A kit developed at the Butantan Institute detects three categories of Escherichia coli bacteria, which is responsible for 30%-40% of cases of an illness that kills 1.5 million children every year

A kit developed at the Butantan Institute detects three categories of Escherichia coli bacteria, which is responsible for 30%-40% of cases of an illness that kills 1.5 million children every year

A kit developed at the Butantan Institute detects three categories of Escherichia coli bacteria, which is responsible for 30%-40% of cases of an illness that kills 1.5 million children every year

A kit developed at the Butantan Institute detects three categories of Escherichia coli bacteria, which is responsible for 30%-40% of cases of an illness that kills 1.5 million children every year

By Karina Toledo

Agência FAPESP – A kit similar to the pregnancy tests sold in pharmacies has been developed by the Butantan Institute to help diagnose the causes of acute diarrhea, an illness that kills 1.5 million children under the age of 5 every year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

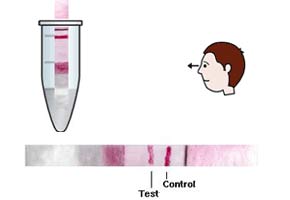

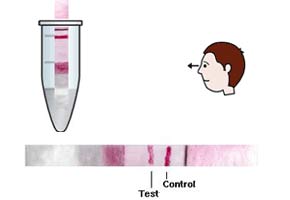

The test can detect three categories of Escherichia coli, the bacteria responsible for 30%-40% of cases of acute diarrhea in developing countries. A paper tape is placed into a previously prepared feces sample, and within 15 minutes, red lines indicate whether one of three types of the bacterium is present.

“There are three types of E. coli that can cause diarrhea, each with different virulent and epidemiological characteristics,” explained Roxane Maria Fontes Piazza, the researcher who coordinated the FAPESP-funded project entitled “Immunodiagnosis of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli."

The test covers two categories considered endemic in Brazil – enteropathogenic (EPEC) and enterotoxigenic (ETEC) diarrhea. It also detects E. coli, which produces the Shiga toxin (STEC). Although this toxin is rare within Brazil, it is a concern to health organizations because it can lead to serious forms of the infection that cause hemorrhagic colitis and kidney failure.

“There is another category very common in Brazil that isn’t detected, the enteroaggregative (EAEC). This is because it doesn’t produce a target protein that allows it to be identified in this type of test,” explained Piazza.

For 13 years, Piazza has been coordinating FAPESP-funded research projects aiming to improve the diagnosis of E. coli infections. The first projects obtained antibodies of the proteins or toxins produced by these three categories of bacteria. Next, the antibodies were tested through other diagnostic methodsvalidate these methods.

“When we had obtained all the antibodies, we decided to standardize the kit so we could make the immunochromatographic test. This method is faster, easier to perform and is not expensive. It can be used in any clinical laboratory,” said Piazza.

The study resulted in de Letícia Barboza Rocha’s dDoctorate, which she earned with a FAPESP fellowship.

How it works

The kit is composed of a tape measuring 6 cm long and 0.5 centimeters wide. The tape is made of three types of paper bonded to a plastic base.

“On one end, there is a highly absorbent cellulose fiber that pulls in the sample and carries it to the part of the tape that has the reagents. Next, the tape has fiberglass to which small gold particles are attached, called colloidal gold. The antibodies are attached to spherical particles, which are just 20 nanometers in diameter,” explained Rocha.

The bacterial antigens, when present, are absorbed by the cellulose fiber and, bond with the antibodies that adhere to the colloidal gold. They continue along the tape until they reach a nitrocellulose membrane, where the test results appear.

“There are many lines on this membrane, and what determines the category of the E. coli present in the sample is the region in which the lines appear on the tape. The reaction is considered positive when both the test and control lines are colored,” said Rocha.

The gold’s function is to make the lines visible. To guarantee the method’s efficacy, however, the tape should not be placed directly in the feces.

Some types of E. coli produce very small quantities of toxins that would not be detected by the exam. “The fecal sample has to be placed in a liquid culture overnight so the bacteria will multiply. Then the tape is placed in the liquid,” said Rocha.

The kit is intended for use in hospitals and clinical laboratories to accelerate detection of the bacteria, which will help health professionals take preventive measures so as to avoid the spread of outbreaks and to adopt adequate therapeutic actions.

According to Piazza, in the usual clinical routine doctor would not request tests or make a diagnosis based only on an analysis of symptoms. “Only when the case is more persistent or when the Shiga toxin-producing bacteria are suspected do they send a sample to a high-quality lab for analysis. The other labs use old and imprecise methods,” he said.

Although the kit has already been produced, the method still needs to be validated. Piazza estimates that the process will take about two years. “Before placing it on the market, we have to patent it and analyze commercial questions such as shelf life,” he explained.

Until this validation occurs, Piazza is coordinating a new research project, also financed by FAPESP, which aims to make large-scale antibody production feasible.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.