Obese and pre-diabetic mice that received the amino acid in water presented weight loss and improved glucose metabolism (image: Unicamp)

Obese and pre-diabetic mice that received the amino acid in water presented weight loss and improved glucose metabolism.

Obese and pre-diabetic mice that received the amino acid in water presented weight loss and improved glucose metabolism.

Obese and pre-diabetic mice that received the amino acid in water presented weight loss and improved glucose metabolism (image: Unicamp)

By Karina Toledo, in Caxambu

Agência FAPESP – After supplementing the water of obese mice with the amino acid taurine for two months, researchers at the University of Campinas (Unicamp) observed that the animals not only showed significant weight loss but also presented various benefits in terms of glycemia control. Data suggest that the treatment could protect the rodents from developing complications such as diabetes.

The results of the FAPESP-funded study, carried out at the Department of Structural and Functional Biology of the Institute of Biology (IB) at Unicamp, were presented by Prof. Everardo Magalhães Carneiro at the 29th Annual Meeting of the Federation of Experimental Biology Societies (FeSBE), held in August in Caxambu (MG).

“Taurine is an amino acid that is not incorporated into the proteins of the body and that seems to have an important role in cell signaling. Our data show that it regulates the intracellular production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or oxygenated water and this correlates with better action on the part of insulin in the peripheral tissues,” Carneiro said.

The researcher explained that taurine is naturally synthesized by the body, mainly in the liver cells and adipose tissue. It can also be obtained by ingesting foods such as meat, fish, seafood, and, to a lesser extent, vegetables.

“Taurine is highly concentrated in the alpha cells of the pancreas, playing a role that we are still trying to determine,” Carneiro said.

The researcher explained that alpha cells are responsible for secreting the hormone glucagon, whose function is to mobilize energy stored as glycogen in the liver during extended periods of fasting to prevent potentially fatal hypoglycemia. In addition, data in the literature indicate that the glucagon produced by alpha cells also stimulates its neighbors, the beta cells, to secrete insulin.

There are three main types of cells in the islets of Langerhans: alpha, beta and delta. Alpha cells stimulate beta cells to produce insulin, and beta cells inhibit glucagon secretion by alpha cells. Delta cells produce the hormone somatostatin, which is capable of inhibiting the secretion of both insulin and glucagon, depending on the circumstances.

“It appears that taurine somehow modulates this paracrine control [in which a hormone produced by a cell controls the activity of a neighboring cell] of insulin, leading to greater or lesser secretion of the hormone, depending on the case,” Carneiro explained.

In previous studies, the Unicamp researchers observed that in normal-weight mice, supplementation with 2% taurine in water increased the secretion of insulin by beta cells, causing the animal’s islets of Langerhans to be more responsive to glucose.

In vitro experiments conducted on the islets of the animals that received taurine supplementation revealed that the cells expressed increased amounts of the active form of the protein PDX-1, a critical transcription factor for insulin synthesis.

In addition, the researchers showed that the insulin receptors in the peripheral tissues of the animals became more activated after supplementation with taurine, advancing the capture of glucose in the muscle tissue and lowering the production of this sugar by the liver. The results were published in The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry.

“It appears that taurine – we still don’t know if directly or indirectly – induces the expression of certain proteins, such as phospholipase-C, PKA and PKC, in beta cells. This culminates in more secretion of insulin. We decided to investigate whether this would also occur in a model of diet-induced obesity,” Carneiro said.

Glycemic homeostasis

To induce obesity, mice were weaned to a diet of 31% pork fat. At approximately 3 or 4 months of age, the animals were already considered obese and pre-diabetic. In other words, they presented glucose intolerance (a delay in removing the nutrient from the blood vessels) and insulin resistance.

“As the adipose tissue increases, the demand for insulin increases, and the beta cells end up hypertrophied. However, the expanded adipose tissue produces inflammatory substances and small amounts of hormones that disrupt insulin’s bonds to its target cell receptors,” Carneiro said.

“Then, even as the body produces more insulin, its action becomes less efficient. This signals the pancreas to produce even more insulin, thus becoming a vicious cycle, leading to failure of the beta cells and consequently to diabetes,” he said.

In parallel, the researcher added, insulin resistance and the resulting difficulty in getting the nutrient inside cells results in further production of glucagon by the alpha cells, increasing the levels of blood glucose even more.

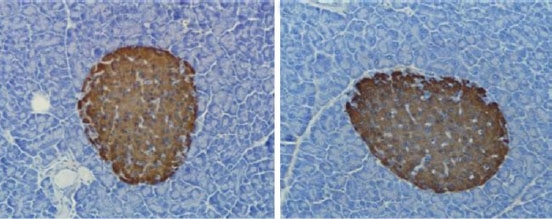

In the same study, some of the mice received supplementation with 5% taurine in water during treatment when fed a high-fat diet. After five months of treatment, analyses revealed that the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas of the animals had diminished in size, taking on a similar appearance as those in the non-obese control group. The levels of insulin secretion also decreased by 45%, accompanied by partial improvement in glucose intolerance and insulin resistance.

In addition to this, there was partial improvement, or 20% and 4% in the glucose and blood cholesterol levels, respectively. This improvement was associated with a 75% increase in the activity of an intermediate protein from the insulin signaling cascade in the liver, but not in the muscles. Some of the results were published in the journal Amino Acids.

Genetic obesity

The researchers then conducted the same experiment using a group of genetically obese mice. In this case, fat accumulation was caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes the hormone leptin in the adipose tissue.

“Leptin is an important hormone for controlling appetite. It acts on the hypothalamus and signals to the body that it is time to stop eating. In carriers of this mutation, the body does not produce leptin, which ends up leading to uncontrolled food ingestion,” Carneiro explained.

In this study protocol, the obese mice received 5% taurine supplementation in water for 60 days. Analyses showed a nearly 16% reduction in the weight of the treated group.

Glucose intolerance diminished by 35%, insulin resistance diminished by 30%, and hepatic glucose production decreased by 28%. However, these parameters were still significantly higher than in non-obese mice.

“Another interesting test that we did with the obese animals was a glucagon tolerance test, which consists of administering this hormone and observing how much glucose that the animal is able to mobilize in the liver. In the obese mice, hepatic glucose production was very high compared with production in the control group, or 94% higher. However, in the obese group treated with taurine, the percentage fell to 39%,” Carneiro said.

The researchers are currently studying the changes in the gene expression patterns of more than 11,000 genes in the hypothalamus induced by the interventions conducted during the experiments.

“Preliminary data indicate that taurine modulates the expression of various genes, thus causing the animal to better adapt in terms of food behavior, which reflects better glycemic control. It also appears to protect the cells of the hypothalamus against endoplasmic reticulum stress, which is a phenomenon involved in the death of several types of cells, including neurons,” Carneiro said.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.