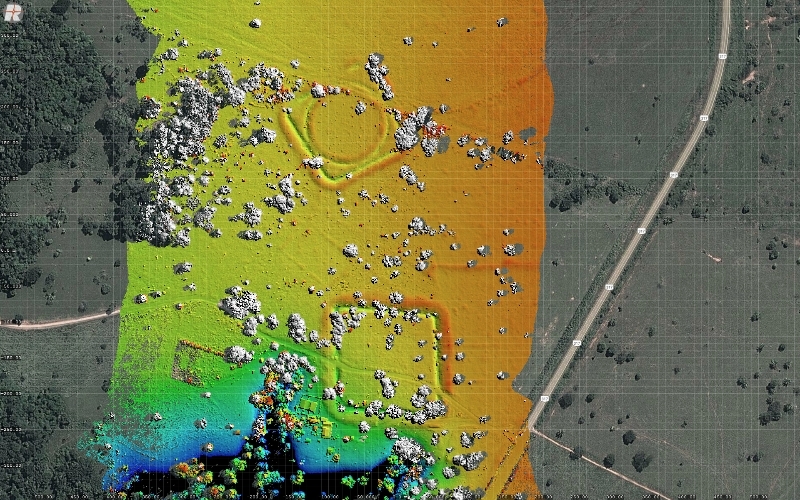

Huge geometric earthworks built by pre-Columbian people are thought to reflect agroforestry (photo: aerial view of the Jacó Sá site, showing geoglyphs / Salman Kahn)

Huge geometric earthworks built by pre-Columbian people are thought to reflect agroforestry.

Huge geometric earthworks built by pre-Columbian people are thought to reflect agroforestry.

Huge geometric earthworks built by pre-Columbian people are thought to reflect agroforestry (photo: aerial view of the Jacó Sá site, showing geoglyphs / Salman Kahn)

By Peter Moon | Agência FAPESP – In the last 30 years, with the expansion of cattle ranching, deforestation in the east of Acre State in Brazil has revealed hundreds of massive geometric earthworks built by pre-Columbian peoples.

The ditched enclosures, technically termed geoglyphs, demonstrate beyond doubt that the region was inhabited thousands of years ago and that the forest cover was partially cleared in that era to make way for agricultural land use. British archeologist Jennifer Watling, currently supported by FAPESP with a postdoctoral scholarship, received her PhD from the University of Exeter, UK, for research on the environmental impact of prehistoric settlers in the region due to the earthworks that they built.

She studied two excavated and dated geoglyph sites: Jacó Sá and Fazenda Colorada. The findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and immediately drew international attention, with news coverage by The New York Times, among many other newspapers and websites.

The Jacó Sá archeological site is reached from Rio Branco, the capital of Acre, by taking the BR 317 highway toward Boca do Acre in Amazonas State. It takes about an hour to drive the 50 km to Jacó Sá. On the way, you can see pastures with Nelore cattle where there used to be primary Amazon rainforest. Remnants of the biome are still visible on both sides of the road in the far distance.

This entire portion of the far west of Acre was covered by primary forest until the 1980s and has since been cleared for cattle ranching. Half the region’s forest cover has been lost.

Ironically, if it were not for the expansion of human settlement in Acre, the more than 450 prehistoric geoglyphs catalogued so far would have remained hidden under forest cover. Many others evidently still are. There are geoglyphs all the way along the Acre, Iquiri and Abunã river valleys between Rio Branco and Xapuri, as well as north of Rio Branco toward Amazonas State.

Neither the shape nor the size of the geoglyphs can be seen from the ground, but they are visible from aircraft flying at 500 m. They can be circular, square or rectangular; concentric circles or circles inside huge squares are frequent.

Their dimensions are colossal, with diameters ranging from 50 m to 350 m. At ground level, the geoglyphs are huge ditches measuring 11 m across and 4 m deep. The immense amount of soil that must have been removed for their construction is striking, indicating that the population size must have been considerable.

The Jacó Sá site has two geoglyphs, both square shaped and about 100 m in length on each side. One has a perfect circle inside the square. Satellite images of these geoglyphs can be found on Google Maps at 9°57′38"S 67°29′51”W.

Watling wanted to discover what type of plant cover existed in the area at the time that the geoglyphs were built. Before the area was cleared, the cover was mainly bamboo forest.

The team set out to answer a number of questions, such as “Was bamboo forest also dominant before the geoglyphs? What was the extent of the environmental impact associated with geoglyph construction?”

Other questions included: “Was the area covered by forest before the arrival of the people who built the geoglyphs, or was it originally savanna? If it was forested, for how long did the cleared areas remain open? What happened to the vegetation once the geoglyphs were abandoned? Did previously cleared areas undergo forest regeneration?”

Forest management

Watling is now carrying out postdoctoral research under the supervision of Eduardo Góes Neves, an archeologist affiliated with the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Archeology & Ethnology (MAE-USP).

In 2011-12, she spent six months working on the archeological digs in Acre, using paleobotany to search for answers. Her findings at Jacó Sá and Fazenda Colorada showed that the bamboo forest ecosystem has been there for at least 6,000 years, which suggests that the bamboo was not introduced by Amerindians, but was instead part of the original landscape.

Human settlement of the area dates from at least 4,400 years ago. The presence of charcoal, especially since 4,000 years before the present (BP), implies that forest clearing and/or management by Amerindians intensified over time.

The main increase in charcoal coincides with the period during which the geoglyphs were built, between 2,100 and 2,200 years BP. Despite the relative ease with which bamboo forest can be cleared (compared with laborious mahogany and Brazil nut tree felling, for example), Watling found no evidence that sizeable clearings were created for geoglyph construction and use.

According to her, this means that the geoglyphs were not built in an area deforested by clear cutting. “On the contrary, they were surrounded by closed-canopy forest. The local vegetation was never kept completely open during the pre-Columbian period. This finding is consistent with archeological evidence that the geoglyphs were used on a sporadic basis, rather than continually inhabited,” Watling said.

“The digs haven’t brought to light a significant number of artifacts, which suggests the geoglyphs were not places of permanent habitation. The Indians didn’t live there.”

Another conclusion is that the geoglyphs were not built in untouched forest that was cleared. The paleobotanic data analyzed by Watling suggest that they were built on previously occupied land in anthropogenic forest that had been fundamentally altered by human activities over thousands of years.

This makes sense now that the region is known to have been inhabited for 4,000 years. In other words, its inhabitants spent 2,000 years managing the forest before the geoglyphs were built. Research on other geoglyphs has shown that the people who built these huge structures grew corn and squash.

According to Watling, forest clearing by fire between 4,000 and 3,500 years BP was followed by a significant increase in the number of palm trees in the forest composition.

No natural explanation exists for this increase in palms: the climate in the region was (and still is) wet and hence favorable to colonization by tall trees forming a dense canopy. Instead, palm proliferation correlates with an overall increase in human land use, as documented by the charcoal data.

Palm trees have many uses. Their fruit is food, their trunks can be used as pillars and beams for longhouses, and their leaves can serve as thatch roofs. According to Watling, this suggests that the first inhabitants of the region cleared some forest and then allowed the proliferation of only the plant species that they found useful. In other words, prehistoric and ancient settlers used primitive forest management techniques for thousands of years.

The absence of charcoal only 500 m away from the geoglyphs implies that the surrounding forest was not cleared. “This suggests the geoglyphs were not designed to be visible at a distance, but to be hidden from view, which is an unexpected finding,” Watling said.

Nazca

The geoglyphs studied by Watling and colleagues from Brazil and the UK were abandoned about 650 years ago, before Europeans came to the Americas. According to the researchers, concordant dates associate the beginning of palm decline with the period of geoglyph abandonment.

The geoglyphs are striking in the beauty and precision of their outlines. Who built these structures? What techniques did they use to achieve such perfect forms?

The first image that comes to mind is of the Nazca Lines, a vast series of giant animal figures and other shapes “drawn” in Peru’s Nazca desert. They were discovered in 1927 and dated to about 3,000 years ago. Seen from the ground, they appear to be endless lines that disappear over the horizon.

Only from above, at altitudes of least 1,500 m, do their shapes begin to make sense. The best-known figures include a hummingbird, a bee and a monkey. These and other Nazca Lines were made famous in the 1970s by Swiss author Erich von Daniken’s book Chariots of the Gods? (English translation published 1969), which sold millions of copies and was made into a documentary film with the same title.

Von Daniken claimed that certain civilizations, such as the Aztec, were visited by some form of intelligent extraterrestrial life and that this explained why the Nazca geoglyphs made sense only from a great height.

Anthropologists disagree, however, explaining that the Amerindians who created these works of art thousands of years ago in Nazca intended to appease the gods and persuade them to make rain. The geoglyphs in Acre are 1,000 km northeast of the Nazca desert, and a lack of rain is not a problem in tropical Acre.

Watling’s postdoctoral research is also focusing on the impact of an indigenous settlement on the forest, in this case at Teotônio, a dig in the Upper Madeira River region of Rondônia, another state in northwestern Brazil. “Teotônio has some of the oldest datings in prehistoric Amazonia. It’s been occupied for at least 5,000 years,” she said.

The article “Impact of pre-Columbian 'geoglyph' builders on Amazonian forests” (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614359114) by Jennifer Watling, José Iriarte, Francis E. Mayle, Denise Schaan, Luiz C. R. Pessenda, Neil J. Loader, F. Alayne Street-Perrott, Ruth E. Dickau, Antonia Damasceno and Alceu Ranzi, published in PNAS, can be read by subscribers at: pnas.org/content/114/8/1868.abstract.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.