Study leads to treatment for myocarditis induced by Chagas disease

Scientists describe the role of immune system cells in chronic inflammation in a study published in the PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases journal.

Study leads to treatment for myocarditis induced by Chagas disease

Scientists describe the role of immune system cells in chronic inflammation in a study published in the PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases journal.

Scientists describe the role of immune system cells in chronic inflammation in a study published in the PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases journal

By Karina Toledo

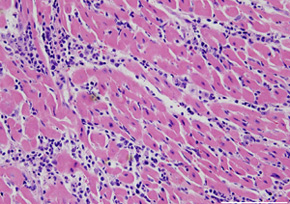

Agência FAPESP – One of the most serious side effects of Chagas disease is the cardiovascular disease that results from chronic inflammation of the heart muscle—myocarditis—and slowly destroys the organ. A recently concluded study at the Universidade de São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine (FMRP-USP) has led to better understanding of the immune system’s participation in this process, which could lead to new treatments.

According to the

results published in December’s

PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, two types of lymphocytes—regulatory T cells (Treg) and T helper 17 cells (Th17)—are primarily responsible for moderating the intensity of the attack from the parasite that causes the illness,

Trypanosoma cruzi.

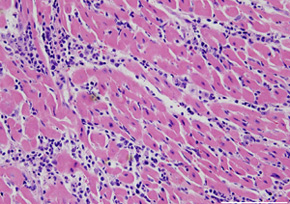

When the numbers of these lymphocytes are reduced in the host organism, the T. cruzi attack is more intense, such that the inflammatory response of the immune system is also greater, thus placing greater strain on the heart. Carriers with high numbers of Treg and Th17 cells in circulation have better prognoses and fewer symptoms in the chronic phase of the disease.

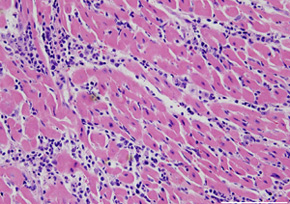

“In mice infected with

T. cruzi, we showed that if the function of these cells is inhibited, the animal dies because of myocarditis. However when the activity of these cells is increased, the result is also bad, as the organism cannot control the spread of the parasite. These cells are necessary but in the right numbers,” explained João Santana Silva, professor at FMRP-USP and coordinator of the

FAPESP-funded study.

In a later phase of the study, based on the analysis of blood samples from Chagas disease patients, the scientists found a clear relationship in humans between the number of Treg and Th17 cells in circulation and the severity of myocarditis.

“Based on this knowledge, it is possible to predict which asymptomatic patients are most likely to develop cardiovascular disease. The discovery also opens pathways [for] the development of medicines able to increase the production of Treg and Th17 cells and modulate the immune response,” he said.

Chagas disease is the main cause of myocarditis. According to Fiocruz’s data, there are an estimated 20 million infected patients in Latin America. Between 25% and 35% of them are expected to develop cardiovascular alterations.

Silva says that, in the past, it was believed that there was no need to treat asymptomatic Chagas disease patients because the main drug used against the parasite (benznidazole) causes harmful side effects and is not recommended in most cases. In addition, the benefits of treatment were not well defined.

Recent studies, however, show that all Chagas carriers develop, albeit very slowly, cardiovascular disease. “The speed of the degenerative effect depends on the production of Treg and Th17 cells,” explained Silva.

These cells, along with the other lymphocytes, are produced in the bone marrow and comprise the white blood cells. “Until…recently, only two types of T helper cells were known: Th1 and Th2. Recently, many other types [have been] discovered, the most important of which [are] Treg and Th17. When this Thematic Project began, we knew very little about the role of these recently discovered cells,” said Silva.

The researcher explained that after becoming activated through contact with the pathogen, the T helper cells produce a series of mediators that activate other types of leukocytes and induce a specific immune response against the antigen.

"Th17 cells are involved in autoimmune diseases such as arthritis and diabetes. That is why it was believed that their presence in the organism was related [to] a bad prognosis. [However,] in our research, we found that during infection [with] T. cruzi and leishmaniasis, [they were] benign. [Th17 cells] work together with Treg [cells] to break the damaging immune response,” affirmed Silva.

The production of Treg and Th17 cells can be influenced by genetic factors, previous illness, diet and the intestinal flora, explained Silva. In the case of Chagas disease, interaction with the parasite is also a determining factor. “We saw in mice that some lines of the parasite stimulate [a higher] production of these cells…. This [production was] determined right at the [onset] of the infection,” he said.

Parallel studies

Until the search for a drug able to modulate Treg and Th17 cell production begins, the FMRP researchers are working together with the USP São Carlos Chemistry Institute to develop new medications that are able to kill T. cruzi in a more efficient manner and with fewer side effects than benznidazole.

“One of the medications being tested has a molecule of ruthenium, [which] releases nitric oxide—the same substance produced by the cells to kill the parasite—together with benznidazole. Tests carried out on mice showed that it was able to kill T. cruzi [at] a dose 1,000 times smaller than…benznidazole [alone],” said Silva.

According to the researcher, the advantage of the candidate medication is its slow and directed release of active compositions, which reduces the side effects.

At the same time, Silva’s team is also investigating the role of Treg and Th17 cells in some types of cancers and infectious diseases, such as leishmaniasis.

In analyzing biopsies from carriers of cutaneous leishmaniasis, which is caused by the protozoan Leishmania braziliensis, the scientists found Treg and Th17 cells in skin lesions.

“We used to believe that patients developed the lesions because of a lack of Treg and Th17 cells, but we can see [that] they are present and very active. If they weren not, the lesions would be much larger,” Silva reported.

In experiments on mice infected with L. braziliensis in the ear region, the scientists blocked the action of Treg and Th17 cells. The illness worsened to such a point that some animals lost their ears.

The group is currently investigating the role of these lymphocytes in infections by Leishmania chagasi, which causes a more serious version of the disease known as visceral leishmaniasis.

“In the case of leishmaniasis, it is also possible to consider treatment with cytokines (molecules produced by defense cells) to stimulate the immune systems of those with the disease,” affirmed Silva.