Study changes policy for treatment of systemic sclerosis

Patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplants should first undergo rigorous cardiac screening, say scientists from USP and Northwestern University.

Study changes policy for treatment of systemic sclerosis

Patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplants should first undergo rigorous cardiac screening, say scientists from USP and Northwestern University.

Patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplants should first undergo rigorous cardiac screening, say scientists from USP and Northwestern University

By Karina Toledo

Agência FAPESP – To better evaluate the risk of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in patients with systemic sclerosis, rigorous cardiac screening is necessary, say researchers from Brazil and the United States in

an article published in

The Lancet. The study’s results are expected to change the way the illness is treated around the world.

Also known as scleroderma, this progressive autoimmune illness affects connective tissue and may lead to vascular alterations and fibrosis of the skin and internal organs, as well as ulcers. The malady is relatively rare, affecting one in 50,000 people, but can be fatal if organs such as the lungs, heart or intestine are seriously damaged.

“Conventional treatment consists of monthly applications of a chemotherapy drug called cyclophosphamide, which is toxic to immune system cells, especially lymphocytes, which mediate disease,” said Maria Carolina Oliveira, one of the study’s authors and a researcher at the

Center for Cell-Based Therapy (CTC in Portuguese)—a

FAPESP Research, Innovation and Dissemination Center (CEPID) located at the Universidade de São Paulo Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine (FMRP-USP).

But according to Oliveira, this treatment only prevents progression of the illness in a small percentage of patients. In about one third of those suffering from systemic sclerosis, the disease worsens to the point of requiring the transplant, which is still considered to be an experimental treatment.

“The goal is to turn off the immune system function so that the immune system stops attacking the organism’s own cells. To do this, we apply aggressive chemotherapy with high doses of cyclophosphamide, together with another drug called antilymphocyte globulin,” explained Oliveira.

Before the procedure, stem cells from the patient’s own bone marrow are collected and frozen. After chemotherapy, this material is returned to the organism so that killer cell production restarts.

This sort of therapeutic approach has also been used for the treatment of some types of cancer, such as lymphoma, and other autoimmune illnesses, such as type 1 diabetes.

“The mortality rate normally associated with this sort of transplant is between 3% and 5%. But in those suffering from systemic sclerosis, the numbers are much higher, reaching 20% in some regions. One of the goals of our study was to discover the causes of this high mortality rate, and the results indicated that in many cases, it is related to heart problems,” said Oliveira.

Together with scientists from Northwestern University in the United States, the Ribeirão Preto team analyzed data from 90 patients who underwent transplants between 2002 and 2011, 31 of whom were treated in Brazil.

“In our retrospective analysis, we noted that two thirds of the patients had no cardiac abnormalities, and one third showed serious heart damage. We observed that the outcome of the transplants in this second group was much worse,” said Oliveira.

According to Oliveira, five patients died during the procedure—four of them because of heart problems. “Pulmonary function worsened in some patients for no apparent reason after the transplant. As the heart and lungs are interrelated, we believe that the cause was cardiac related,” she said.

Cyclophosphamide is a cardiotoxic drug, explained Oliveira. In addition, the procedure overtaxes the heart because of the use of large volumes of liquid. The association of the transplant and previous heart disease seems to increase risks during the procedure and result in deterioration of cardiopulmonary function post-transplant.

Follow-ups for five years after transplantation showed that the survival rate was 78% at five years (after eight relapse-related deaths), and relapse-free survival was 70% at five years.

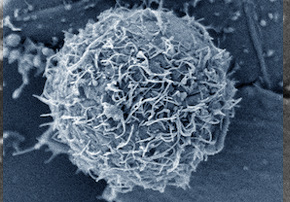

Julio Voltarelli

Based on the results of the study, the researchers proposed that rigorous cardiac screening, including echocardiograms, electrocardiograms, catheter and magnetic heart resonance, be adopted as a prerequisite for the treatment of systemic sclerosis with HSCT.

“Oftentimes, the problem goes unnoticed. The heart is already weakened, but the patient doesn’t have any symptoms,” affirmed Oliveira.

The researcher emphasized, however, that new studies are still necessary to determine exactly which level of heart damage should make the patient ineligible for transplantation.

“There is a safety limit. We are planning a prospective study—also in partnership with Northwestern and possibly centers in France and England—to examine patients and follow their progress so we can see how they evolve,” she said.

The January 28th online edition of The Lancet also ran a commentary on the study signed by three prominent British specialists in the field: John Snowden, Mohammed Akil and David Kiely.

“This is the most extensive study ever done on the effects of HSCT in patients with systemic sclerosis. The five-year follow-up period after transplant allows for definitive affirmation of the effectiveness of the procedure, as it showed 70% relapse-free survival after five years and significant improvement in measurements in specific organs,” highlighted the specialists.

“Due to the high prevalence of cardiac-related deaths related to the treatment and the possibility of hidden cardiopulmonary disease, the proposed complementary evaluation is the correct approach for increasing safety,” they added.

The printed version of the journal, to be released in February, is also expected to contain the obituary of researcher Julio Cesar Voltarelli, one of the study’s authors, who died in March 2012.

Voltarelli was coordinator of the FMRP-USP Hospital das Clínicas’ Immunogenetic Laboratory and Bone Marrow Transplant Unit. He led the HSCT study on the treatment of autoimmune diseases in Brazil.