Thanks to the limited iron found in the host liver, infection by the malaria parasite prevents the occurrence of a second, more severe infection, according to a study published in Nature Medicine with Brazilian participation

Thanks to the limited iron found in the host liver, infection by the malaria parasite prevents the occurrence of a second, more severe infection, according to a study published in Nature Medicine

Thanks to the limited iron found in the host liver, infection by the malaria parasite prevents the occurrence of a second, more severe infection, according to a study published in Nature Medicine

Thanks to the limited iron found in the host liver, infection by the malaria parasite prevents the occurrence of a second, more severe infection, according to a study published in Nature Medicine with Brazilian participation

By Fábio de Castro

Agência FAPESP – In malaria-endemic areas it is common for people to be bitten several times by the mosquito that transmits the disease. But thanks to iron regulating hormones in the host liver, the infection caused by the malaria parasite prevents the occurrence of a second infection.

That is the conclusion of a study realized by a group of international scientists, with Brazilian participation. The results of the study were published in the May edition of Nature Medicine.

According to the authors, the study could have an impact on global health policies that recommend iron supplements for anemic children. In malaria endemic areas, iron supplementation could cause superinfections.

The study was conducted that the Institute of Molecular Medicine (IMM) in Lisbon, Portugal, with the participation of scientists from Oxford University. Research was coordinated by Maria Mota, director of the IMM’s Malaria Unit, and had collaboration from Sabrina Epiphanio, from Universidade Federal de São Paulo’s (Unifesp) Biological Sciences Department.

Epiphanio collaborated with the study during her post-doctoral research, conducted from 2005 to 2008 at Mota’s laboratory in IMM. The first author of the study, Silvia Portugal – currently a researcher at the U.S. National Institutes of Health, worked for three years in Epiphanio’s laboratory at Unifesp as visiting researcher.

The Brazilian scientist is currently conducting a study on the respiratory syndrome associated with malaria, with FAPESP funding under the Young Investigators at Emerging Institutions program.

According to Epiphanio, who has worked with malaria-related topics for nine years, the study published by the international group is one of those rare projects that simultaneously examine the liver and blood phases of malaria, simulating the situation in an endemic area in which the victims can be bitten several times by transmitting insects.

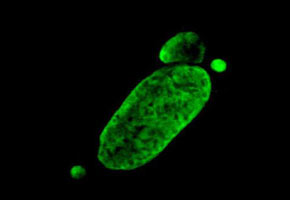

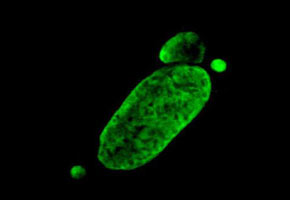

“We utilized models of malaria-infected mice for the blood phase and infected them a second time with the liver phase. When we measured the infection in the liver of the animals we saw that the response to the second infection was much lower than the first. This perhaps explains why not everyone who contracts the disease in endemic areas end up dying,” she tells Agência FAPESP.

The system functions as control mechanism. If the response to the second infection was as intense as the first, the host would have a superinfection, developing a more severe form of the disease, like cerebral malaria, a severe anemia or a respiratory syndrome. In these cases, the mortality index is much higher and the reversal of the clinical scenario becomes very difficult.

“Our first suspicion was that the protection afforded by the second infection would be related to an immune system response. But we conducted a series of experiments with lymphocyte-deficient insects and verified that this did not affect the phenotype: independently of the immune response, the impact of the second infection was always lower,” comments the researcher.

Iron supplementation

With the hypothesis of the immune response discarded, the group continued with the tests and discovered that the protection produced by the second infection was related to increased levels of hepcidin – a hormone produced by the liver that redistributes iron present in the organ to the rest of the organism.

“The parasite needs iron to develop and with the first infection, it removes iron from blood circulation, also reducing its abundance in the liver. In the second infection, the liver has very little available iron and the parasite cannot multiply, preventing a superinfection,” explains Sabrina Epiphanio.

The study shows that the greater the number of cells infected in circulation, the greater the concentration of hepcidin, which takes iron out of circulation, making hepatocytes iron-deficient and impeding superinfection.

“When we utilize drugs that block the production of hepcidin – both in vivo and in vitro – the phenotype was reverted, that is, the iron levels were maintained and the second infection was as severe at the first,” she explains.

The study’s main contribution, according Epiphanio, could be its impact on global public policy for iron supplementation in areas where there is high anemia incidence. In many cases, the areas are the same as malaria-endemic zones.

“Giving iron to anemic children in these regions could contribute to superinfection of malaria in endemic area. The literature shows that in Zanzibar, anemia prevention programs that had iron supplementation programs were followed by spikes in the indices of malaria,” says Epiphanio.

The article Host-mediated regulation of superinfection in malaria by Silvia Portugal et al, can be read by subscribers of Nature Medicine at: www.nature.com/nm/journal/v17/n6/full/nm.2368.html.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.