Researchers achieve effective action against Leishmania by treating infected organs with a drug originally used against parasitic diseases in animals.

Researchers achieve effective action against Leishmania by treating infected organs with a drug originally used against parasitic diseases in animals.

Researchers achieve effective action against Leishmania by treating infected organs with a drug originally used against parasitic diseases in animals.

Researchers achieve effective action against Leishmania by treating infected organs with a drug originally used against parasitic diseases in animals.

By Fábio de Castro

Agência FAPESP – A study performed by researchers at the Instituto Adolfo Lutz in São Paulo found that a medication used in veterinary medicine to treat certain parasitic diseases proved highly effective in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in animal models.

The study, the results of which will soon be published in the journal Experimental Parasitology, showed that buparvaquone showed effectiveness similar to that of the standard medication used to treat leishmaniasis, but with a dose that was 150 times smaller.

According to the study’s coordinator, André Gustavo Tempone of the Instituto Adolfo Lutz, it was already known that buparvaquone is one of the most active medications against Leishmania in vitro, but its action in live disease models had never been reported.

“There is great expectation that these results will lead to future testing in humans, as the medication has already shown to be very effective in in vitro tests. But in animal models, its action was very limited, as there was one catch: the drug did not reach the animal’s liver and the spleen, which is where Leishmania infection occurs,” Tempone told Agência FAPESP.

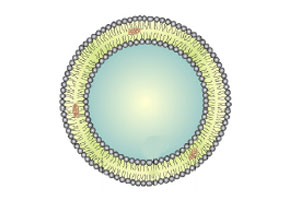

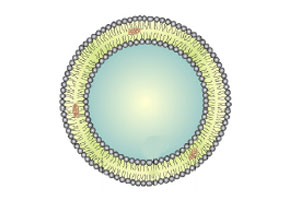

To address this issue, the researchers used liposomes, which are spherical vesicles used to direct the medication toward the infected cell in a precise manner. “With the liposomal carrier, we were able to show for the first time that it is possible to use the medication to treat visceral leishmaniasis,” Tempone said.

The study was conducted as part of the FAPESP-funded project titled “Therapeutic combinations for visceral leishmaniasis: the antileishmanial potential of calcium channel blockers and the use of liposomal nanoformulations,” which was part of the Regular Research Support program that ended in July of 2011.

The study is also part of FAPESP fellow Sandra Reimão’s doctoral research. Tempone is Reimão’s advisor, and in addition to these two, other authors contributing to the article were researchers Fábio Colombo and Vera Pereira-Chioccola, who are also from the Instituto Adolfo Lutz Parasitology Department.

Tempone currently coordinates the FAPESP-funded project “From trypanosomes to Leishmania: novel drug candidates for the treatment of neglected parasitic diseases,” which is part of the FAPESP-King's College London scientific cooperation agreement.

A simpler formula

According to Tempone, the new study is especially important because it examines ways of adapting already existing medications.

“This type of study—known as piggy-back chemotherapy—is important, even though it does not seek new drugs, because the public health system can place medications on the market more quickly. As we are looking at a drug that is already in use, we do not have to go through toxicity testing, for example. We can develop the new application from a more advanced starting point,” he explained.

He says that buparvaquone is a drug used in veterinary medicine, especially in Europe, to treat a parasite infection. Its anti-leishmaniasis action was revealed for the first time in a study published in 1992.

Testing at the time, however, was performed on visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania donovani, which is a predominant parasite in such countries as India. In Brazil, the predominant parasite is Leishmania chagasi.

“This drug was followed for many years by researchers in parasitology who attempted to utilize it, as it was highly efficient in vitro. What was different about our work is that we managed to make the drug work in animal models with the help of the liposomes,” said Tempone.

The researchers used conventional liposomes—not nanoliposomes—so that the formulation would be simpler. “We thought of the industry’s needs and how it could produce the drug in the future. That is why we were sure to create the simplest formulation possible so as to facilitate production,” he said.

The formulation they used included the use of a modified phospholipid that is more efficiently directed toward the host cells, which, in leishmaniasis, are the macrophages present in the animal’s liver and spleen.

“We used Leishmania chagasi-infected hamster models. The liposomal formulation carried the drug to the animals’ liver and spleen and showed that it can reduce the parasite levels in the spleen by 89% and in the liver by 67%. Most importantly, however, is the fact that to achieve the same effectiveness as Glucantime (meglumine atnimoniate), the standard drug used in leishmaniasis treatment, we only needed to use a dose that was 150 times smaller.”

Thanks to real-time PCR technology, the researchers were able to use molecular biology as a tool in the laboratory. “By using real-time PCR, we managed to quantify the action of a drug in an animal model precisely. This has made our studies on new medications easier,” said Tempone.

From this point forward, the researchers will work on new studies with animal models to define the best means of administration, correct dosage and the ideal time period for treatment. “We will also investigate the details of the dynamics and liposomal biodistribution of the medication in animal models,” he said.

The article “Effectiveness of liposomal buparvaquone in an experimental hamster model of Leishmania (L.) infantum chagasi” (doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2012.01.010) by Juliana Reimão and others can be read by Experimental Parasitology subscribers at www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014489412000276.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.