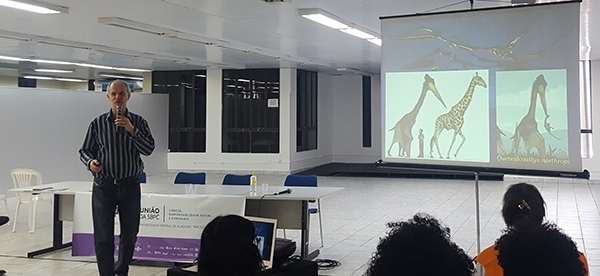

An area of Paraná State may soon become one of the only places apart from China and Argentina where fossilized embryos of extinct flying reptiles have been found, according to Brazilian paleontologist (photo: Elton Alisson / Agência FAPESP)

An area of Paraná State may soon become one of the only places apart from China and Argentina where fossilized embryos of extinct flying reptiles have been found, according to Brazilian paleontologist.

An area of Paraná State may soon become one of the only places apart from China and Argentina where fossilized embryos of extinct flying reptiles have been found, according to Brazilian paleontologist.

An area of Paraná State may soon become one of the only places apart from China and Argentina where fossilized embryos of extinct flying reptiles have been found, according to Brazilian paleontologist (photo: Elton Alisson / Agência FAPESP)

By Elton Alisson, in Maceió | Agência FAPESP – Cruzeiro do Oeste, a small town in Paraná State, Brazil, could soon join two regions of China and a region of Argentina as the only places where pterosaur eggs have ever been found.

One of the world’s leading experts on these prehistoric flying reptiles, which were distant relatives of the dinosaurs and became extinct at the same time, is Brazilian paleontologist Alexander Kellner, director of the National Museum, which is Brazil’s oldest scientific institution and one of the largest museums of natural history and anthropology in the Americas. It belongs to the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Kellner believes it is just a matter of time before pterosaur eggs are also found in the region of Cruzeiro do Oeste.

“It’s possible that pterosaur eggs will turn up there because we’ve already found many pterosaur fossils together in the area,” Kellner said during a presentation delivered on the third day of the 70th Meeting of the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC), held on July 22-28, 2018, at the Federal University of Alagoas (UFAL).

In 2014, Kellner and colleagues at the Paleontology Center (CENPALEO) of Universidade do Contestado in Mafra, Santa Catarina State, identified a group of 47 pterosaur fossils in Cruzeiro do Oeste. They decided it was a hitherto unknown species, which they named Caiuajara dobruskii. The species lived some 80 million years ago in southern Brazil, according to the researchers.

At the end of 2017, Kellner and Chinese colleagues unearthed the largest pterosaur egg find ever in the Gobi Desert, northwest China, with 215 eggs. Estimated to be 120 million years old, many were preserved in three dimensions.

Previous finds in China and Argentina, made in 2011, support the hypothesis that pterosaur embryos will also be discovered in Cruzeiro do Oeste, according to Kellner.

“So far, only three large accumulations of pterosaurs belonging to the same species have been found in the world: in the Hami region of Xinjiang in China, in Argentina, and in Cruzeiro do Oeste. Embryos have been found in China and Argentina. Not yet in Cruzeiro do Oeste, but it’s just a matter of time,” he said.

The pterosaur egg find in China gave researchers a better understanding of the pterosaur’s evolution. It was the first vertebrate to evolve powered flight and lived between 220 million and 66 million years ago. Powered flight has evolved only four times: first in insects, then in pterosaurs, birds and bats.

The eggs resembled those of lizards. The embryos had well-developed hind limbs, but their forelimbs were undeveloped, so the researchers concluded that when pterosaurs hatched they could walk but not fly and required some parental care until they became independent.

“This knowledge has been made possible by the find. Hitherto, we’ve always assumed pterosaurs could fly as soon as they hatched,” Kellner said.

The researchers also identified a female containing two eggs among the fossils found in China. The discovery showed the animal had two oviducts (tubes that transport eggs from the ovary to other organs of the reproductive system or directly to the exterior) instead of one, as in birds.

“Besides eggs, in China, we found hundreds of pterosaur bones that can be used together with the materials we discovered in Cruzeiro do Oeste to study the ontogenetic variations of these animals,” Kellner said. Ontogeny is the developmental history of an individual organism from the embryo.

Studying the pterosaur’s ontogenetic variations will enable paleontologists to expand their knowledge of the changes in the form of these animals, which were highly diversified throughout their long existence.

“This is important because when you find different animals with totally different structures, they may be from the same species but at different ontogenetic stages. We can reach this conclusion only if we find materials from the same population, such as those discovered in China and Cruzeiro do Oeste,” Kellner explained.

Preservation problems

Although pterosaur fossils have already been found on practically all continents, discoveries of well-preserved materials from these animals are rare. This is because many physical, chemical and geological processes are involved in fossil formation and affect the preservation of the material, Kellner explained.

“It’s extremely difficult for pterosaur fossils to be preserved, and that’s why finds are so rare,” he said. “For example, fossils have been found with wing spans of more than 5 meters and bones only 2 millimeters thick.”

Relatively well-preserved pterosaur fossils have been found in an area known as the Cambridge Greensand near Cambridge, England, and in Solnhofen, Germany. One of the best specimens was found in Brazil in the Araripe Basin, where the states of Ceará, Piauí and Pernambuco meet.

“The fossils found in the Araripe Basin are among the best in the world. Practically no discussion on general matters relating to pterosaurs can afford to ignore the material we found there,” Kellner said.

However, the optimal state in which the material found in the Araripe Basin was preserved does not mean the archeological site is protected. On one of his expeditions to the area for fieldwork, Kellner found the base of a pterosaur skull being used as a paperweight in a local bar.

“We had no prior knowledge of the internal structure of this pterosaur skull base, which is highly similar to that of birds such as owls,” Kellner said.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.