An antibody developed in a USP study stimulates the immune system to combat paracoccidioidomycosis, an illness common in rural areas that mainly affects the lungs

An antibody developed in a USP study stimulates the immune system to combat paracoccidioidomycosis, an illness common in rural areas that mainly affects the lungs

An antibody developed in a USP study stimulates the immune system to combat paracoccidioidomycosis, an illness common in rural areas that mainly affects the lungs

An antibody developed in a USP study stimulates the immune system to combat paracoccidioidomycosis, an illness common in rural areas that mainly affects the lungs

By Karina Toledo

Agência FAPESP – Researchers at the Universidade de São Paulo School of Pharmaceutical Sciences (FCF-USP) have tested a new vaccination strategy against a little-known but potentially incapacitating illness called paracoccidioidomycosis.

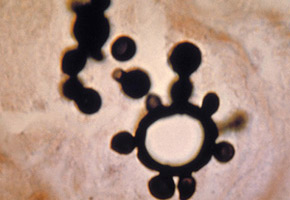

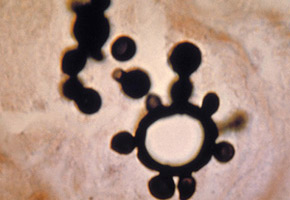

Caused by the fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, which is commonly found in rural areas, the illness causes a chronic inflammatory process and leads to the formation of fibrosis in affected tissues.

Because its main form of contagion is by inhalation, the most common long-term effect of the disease is chronic obstructive lung disease. However, the fungus can also affect the skin, mouth, larynx, spleen and liver, aside from infiltrating bones, joints and the central nervous system.

“Existing treatment is slow, oftentimes requires hospitalization and causes significant collateral effects. Because of this, we chose a vaccine treatment that stimulates the immune system to combat the disease. However, we are also testing the vaccine in a prophylactic protocol to see if it is able to prevent infection,” said Suelen Silvana dos Santos, whose doctoral studies are being overseen by FCF-USP professor Sandro Rogério de Almeida with FAPESP funding.

It is estimated that 10 million people are infected with P. brasiliensis in Latin America, mostly in Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela and Colombia. Of these, only 2% develop the disease, usually in association with poor nutrition, alcoholism, smoking or pre-existing illnesses.

When the mycosis manifests itself, however, it becomes a public health concern, as mortality rates are high, and those who survive are oftentimes unable to work.

“Research has shown an incidence of three cases for each 100,000 inhabitants. However, I believe that this number is underestimated because reporting cases is not required,” said the researcher.

According to Santos, 90% of the cases are caused by the chronic form of paracoccidioidomycosis, which takes years to develop and show clinical symptoms. However, the illness may also manifest itself in an acute form, which is more aggressive and mostly affects young people.

The main drug used today in the more serious phase of the illness is the antibiotic amphotericin B, which is highly toxic and requires long periods of hospitalization. After release, the patient must be monitored for the evaluation of liver and kidney function in addition to additional treatment to prevent relapses.

“This is why we bet on a therapeutic vaccine. The strategy is to direct an antigen of the fungus to dendritic cells to initiate a specific immune response within the organism against P. brasiliensis,” explained Santos.

Directed response

Dendritic cells are key parts of the immune system. After phagocytosing antigens, they migrate to the lymphatic organs and present the invaders to T cells, which are responsible for the adaptive immunological response that is specific for each disease.

When the antigen is presented to the T cells, an immunological memory is created that prevents new infections once the illness has been suppressed.

“If we manage to send the antigen directly to the dendritic cells, we can avoid setting off an overblown, undirected immune response, which could destroy the tissue cells affected by the fungus,” affirmed Santos.

To do this, the researchers developed an antibody called anti-DEC205, which was only able to bind to receptors on dendritic cells. One of the fungal peptides, called P10, was fused to this antibody.

“P10 is an amino acid sequence taken from the fungus’ main glycoprotein, gp43. It works as an antigen—in other words, it induces a specific immunological response to the fungus,” explained Santos.

Both gp43 and P10 were discovered in a series of studies being carried out since the 1980s under the direction of Luiz Rodolpho Travassos, a retired professor at the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), with FAPESP funding.

During his doctoral studies, USP Biomedical Sciences Institute (ICB-USP) professor Carlos Pelleschi Taborda—who collaborated on Santos’ study—tested the immunization power of P10 in mice, with encouraging results.

To develop the fusion of anti-DEC205 to P10, Santos collaborated with Silvia Beatriz Boscardin, who is also from ICB-USP.

Boscardin, who brought the technology to produce antibodies fused with antigens to Brazil, is currently testing the same strategy to develop vaccines against malaria and other infectious diseases.

“During a ten-day immunization protocol, we compared the immune response induced by isolated P10, anti-DEC205/P10, and a control antibody that was incapable of binding to dendritic cell receptors because of a mutation,” told Santos.

The objective was to activate the T cells that produce interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), a pro-inflammatory cytokine important for combatting the fungus. The response using the directed strategy was two times greater than when the antigen was administered alone. Administration of the control antibody had basal results, as expected.

“We used 200 times less peptide with anti-DEC 205 than isolated P10, and the immune response was still greater. This shows that the immunization strategy is promising,” said Santos.

However, the researcher said that it was necessary to add a substance to anti-DEC 205/P10 to stimulate the maturation of the dendritic cells. “When the guidance is performed without this stimulus, the dendritic cells become tolerant. Normally, maturation is stimulated by the disease’s inflammatory process, but in the case of the vaccine, it was necessary to stimulate the cells,” he explained.

The data were presented at the 18th Congress of the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology (ISHAM), which was held in Germany in June. The poster won an award in the “Basic Mycology” category.

“We still don’t have the results of the therapeutic protocol. The animals have been infected, but as the disease takes time to develop, the work will take more time to be completed,” said Santos.

The research also involved collaboration with Karen Spadari Ferreira from the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP) and Master’s degree candidate Eline Rampazo from ICB-USP.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.