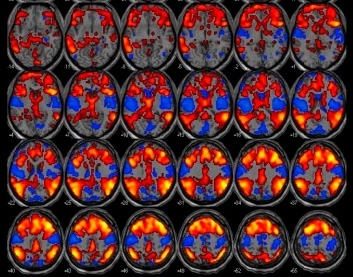

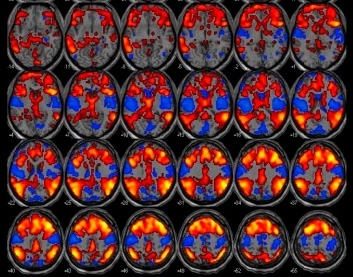

When an epileptic discharge occurs, the researchers use fMRI to identify the brain areas and neural circuits that are activated (image: release)

Collaboration between Brazilian and British researchers involves the simultaneous use of EEG and fMRI to study brain activity.

Collaboration between Brazilian and British researchers involves the simultaneous use of EEG and fMRI to study brain activity.

When an epileptic discharge occurs, the researchers use fMRI to identify the brain areas and neural circuits that are activated (image: release)

By Karina Toledo

Agência FAPESP – What is the relationship between sleep patterns and epilepsy? Researchers in Brazil and the United Kingdom are trying to answer this question using electroencephalography (EEG) combined with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

They expect their findings to help improve the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of epilepsy.

The scientists involved are affiliated with the Universities of Campinas (UNICAMP) and São Paulo (USP) in Brazil and Nottingham and Birmingham in the UK. Their research collaboration is being conducted under the aegis of the Brazilian Research Institute for Neuroscience and Neurotechnology (BRAINN), one of the Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers (RICDs) supported by FAPESP, and FAPESP’s Program of Interinstitutional Cooperation to Support Brain Research (CINAPCE). The research is also funded through a project selected in a call for proposals issued under a cooperation agreement between FAPESP and the two UK universities.

“Our focus is generalized epilepsy, which used to be called idiopathic or primary epilepsy. In these cases, seizures often occur during sleep, and especially during the transition between sleep and wakefulness. Episodes are also typically associated with lack of sleep,” said Fernando Cendes, a researcher at UNICAMP and coordinator of BRAINN.

In generalized epilepsy, seizures appear to start in all parts of the brain simultaneously and have no identifiable onset. This form of the disease is believed to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Patients have no cognitive impairment or visible structural brain abnormalities, which may exist only at the molecular level. Seizures are the main symptom, resulting from sudden alterations in the brain’s electrical activity.

“An EEG can detect epileptiform interictal discharges, which show up as abnormal acute waves known as spike-slow wave complexes. These are characteristic of generalized epilepsy and may serve as markers,” Cendes said.

Sleep patterns

When an epileptic discharge occurs, the researchers use fMRI to identify the areas of the brain that are activated and the neural circuits involved.

“Functional MRI tracks the blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) signal,” Cendes said. “Oxygen levels rise in active brain regions, and the BOLD signal changes accordingly. We can also study how the physiological patterns displayed by an EEG change when the patient is asleep, awake, and resting with eyes open or closed. By submitting people with epilepsy and healthy volunteers to these tests, we can compare the results and analyze the differences.”

Volunteers sleep inside an fMRI scanner while being connected to an EEG recording system by electrodes. The examination is limited to the initial stages of sleep because it lasts only an hour. “This is enough time to cover the transition from wakefulness to sleep,” Cendes said. “In that time it’s possible to observe wave and brain activation patterns, analyzing the normal rhythms of patients with epilepsy and healthy volunteers.”

Part of the study is led by Cendes at UNICAMP’s general hospital (Hospital das Clínicas), and part is being conducted at Birmingham University Imaging Center (BUIC) under its director, Andrew Bagshaw. In both cases the researchers use 3-Tesla scanners so that the data can be compared.

“We observe what happens in the sleeping brain and compare each individual’s sleep patterns with the patterns of their brain activity while awake,” Bagshaw said. “I’m interested in finding out what the brain should be doing during sleep. We can use these methods to explore how the involved processes are affected by epilepsy and enrich our understanding of both phenomena.”

“We’ve applied these tests to some 25 people to date,” Cendes said. “The data are currently being analyzed. It will probably be necessary to collect more data, since the degree of alteration was very small. Whenever we see weak signals, we need a larger number of observations in order to be sure they’re not isolated events.”

The significance of the collaboration with UK researchers, according to Cendes, resides in the opportunity to develop new MRI acquisition techniques that permit more sensitive assessments of the brain alterations involved in epilepsy. “With minor adaptations, these techniques can be used to study other brain diseases such as depression, dementia and schizophrenia,” he said.

“I’ve been particularly interested in Professor Cendes’s work at UNICAMP for some time,” Bagshaw said. “He uses imaging methods to determine both the type and the severity of epilepsy cases in his patients so as to have a basis on which to plan treatment. Although he’s responsible for a relatively large number of patients, Cendes has used these new approaches to create personalized treatments for the individuals under his care.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.