Over 30 years of research on the indigenous tribe in Central Brazil is brought together in a study

Over 30 years of research on the indigenous tribe in Central Brazil is brought together in a study

Over 30 years of research on the indigenous tribe in Central Brazil is brought together in a study

Over 30 years of research on the indigenous tribe in Central Brazil is brought together in a study

By José Tadeu Arantes

Agência FAPESP – Understanding the other, those different from ourselves, is the eternal challenge of anthropologists. Aside from the scientific repertory, they must develop an intensely receptive attitude, a silent capacity for observation that enables them to see beyond the apparent surfaces of beings and phenomena to understand the connections underneath that give them meaning. Even more, in the words of the French anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu, the rules of a society cannot be explained verbally but are habits accumulated over uncountable generations.

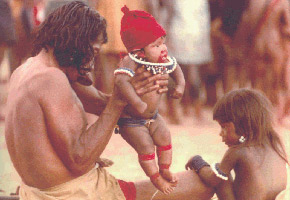

Vanessa Rosemary Lea’s book Riquezas Intangíveis de Pessoas Partíveis [Intangible Riches of Breakable People] is a testimonial to this challenge. With nearly 500 pages of dense text, Lea’s work is the fruit of over three decades of her immersion in the material and non-material universe of the Mebengokre people of Central Brazil. A Professor at the Philosophy and Human Sciences Institute at the da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (IFCH-UNICAMP), Lea received funding from FAPESP under its Research Support-Publications Program.

The Mebengokre, indigenous people of the Macro-je stock—which Lea does not refer to by the popular but prejudiced and racist name Kayapó, which literally means “like a monkey”—first caught the attention of the British scholar in 1971 when at the height of the Brazilian military dictatorship, they appeared in the media in protests against construction of the BR-080 highway, which crossed their ancestral lands. “I was attracted by their proud attitudes,” affirms Lea.

The research itself began in 1978 in the village of Kretire, Mato Grosso State. Throughout the following years, Lea visited and stayed in many villages, including a seven-month residence in Mebengokre territory between 1981 and 1982. At that time, she was symbolically adopted as a “daughter” by chief Ropni Metyktire, referred to in the media as Raoni. Altogether, the time the anthropologist spent living with her chosen people adds up to nearly two years.

Living on the frontier where the national territory is being incorporated by the hegemonic social order, the Mebengokre have been impacted by a number of controversial “developmentalist” initiatives: first, the aforementioned construction of the BR-080 highway; next, the Cachimbo military base, with subterranean installations for nuclear testing; later, the rapid expansion of soy farming; and today, construction of the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant.

Lea testifies to the proud resistance of this people and their complex assimilation of the values of the society surrounding them—with growing fascination and dependence in terms of industrialized goods (nekretex), to which their ancestors (mekukamare) had no access.

Dealing with insistent requests for “gifts” was one of the pieces of the complicated puzzle the anthropologist set out to assemble. “The relationship with goods, both material and immaterial, directed my research. It made me define, in short, my book as an archaeological study of the concept of wealth among the Mebengokre,” she said.

“I came to understand that the House (with a capital H) is a fundamental element in Mebengokre society. It should not be confused with mere habitation because while habitation is a physical institution, the House holds a status equivalent to a legal entity. Each House, which may be composed of one or some neighboring homes, occupies a fixed place in the circle that makes up the village, which is located according to the daily trajectory of the sun from east to west,” said Lea.

“Each House has a distinct collection of personal names and hereditary prerogatives consecrated by myths. Physical separation of its members in the case that some may move to other villages does not affect the notion that the person belongs to a certain House,” said Lea.

The researcher emphasizes that the women of each House are always uterine relatives. Additionally, House names and prerogatives are always passed along maternal lines. It is the uterine (female) and not agnatic (male) lineage that determines transmission.

“At the center of the village is the ngà, or ‘men’s house.’ In the past, a boy was taken out of his mother’s House at the age of 8 or 10 and taken to the ngà, where he would live until he was recognized as an adult when his first child was born and he went to live in his wife’s House. This has changed some, but today, a man only goes to his mother’s House or his wife’s House. If he separates from his wife, he has to leave her House,” said the anthropologist.

Another fundamental element related to the idea of House is the onomastic system or the structured set of names. Names are added to a child’s name as she grows and her inheritance becomes clear. There are “common names” and “beautiful names.” The difference is that the second type is confirmed ceremonially.

Names refer to the day-to-day lives of people, the elements, the flora, the fauna, rural products or new goods that are now being assimilated due to contact with the surrounding society. A large number of names designate physical or behavioral attributes, such as “tall,” “thin,” “crybaby” or “glutton.” However, apparent simplicity can be deceiving, as many names carry a number of meanings.

“Most people have from six to fifteen names. It’s considered indecent for an adult to have fewer than five. During my research in Kretire, there was a boy with thirty-two names. When the person dies, his set of names is disintegrated. This way, there are no two people with exactly the same name,” said Lea.

According to the researcher, this intangible wealth, which is constellated in the plethora of inheritable prerogatives, is so defining for the Mebengokre that when faced with the impact brought on by the impending construction of the Belo Monte Dam, a woman named Kena affirmed in 2011, “As long as we have our names, we won’t disappear.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.