Saber-toothed cats of the genus Smilodon devouring their prey. A loss of diversity occurred due to fewer herbivores to prey on, which led to extinction (Illustration: Felipe Capoccia/UNICAMP)

Cross-referencing climate data and fossils from around 15 million years ago shows that the decline in prey availability may have played a role in the extinction of these felines. Another study cites competition with elephants and an increase in predators as factors that reduced the once diverse antilocaprids to a single species today.

Cross-referencing climate data and fossils from around 15 million years ago shows that the decline in prey availability may have played a role in the extinction of these felines. Another study cites competition with elephants and an increase in predators as factors that reduced the once diverse antilocaprids to a single species today.

Saber-toothed cats of the genus Smilodon devouring their prey. A loss of diversity occurred due to fewer herbivores to prey on, which led to extinction (Illustration: Felipe Capoccia/UNICAMP)

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – In two new studies supported by FAPESP, researchers at the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, have shed light on how interactions between predators and prey influenced the extinction of saber-toothed tigers and the demise of the diverse antilocaprid species, which are now reduced to a single species: the American antelope.

In the first study, published in the Journal of Evolutionary Biology, the researchers used fossil databases, body size estimates, and data on climate variation in North America and Eurasia over the last 20 million years.

This allowed them to trace the evolutionary history and interactions that may have influenced the extinction of saber-toothed tigers. These felids are characterized by their elongated canines, suggesting that they were specialized predators of large animals.

“One of the hypotheses that’s received the most attention in the literature was that the end of saber-toothed tigers could be linked to the extinction of megafauna at the end of the Pleistocene, which occurred between 50,000 and 11,000 years ago. These large animals became extinct due to climate change and human actions, and as a result, the predators were left without their main prey,” says João Nascimento, the lead author of the studies, which were conducted during his PhD at the Institute of Biology (IB-UNICAMP) with a scholarship from FAPESP.

“However, we found that the process began millions of years earlier. Throughout the group’s history, there have been several different species of saber-toothed cats. Our study shows that the extinctions of some of them, throughout the group’s history, generally occurred at times when prey diversity was lower,” he explains.

In the other study, published in the journal Evolution, the authors observed a correlation in the opposite direction. The increase in predator diversity caused a decline in the species diversity of a group of herbivores known as antilocaprids.

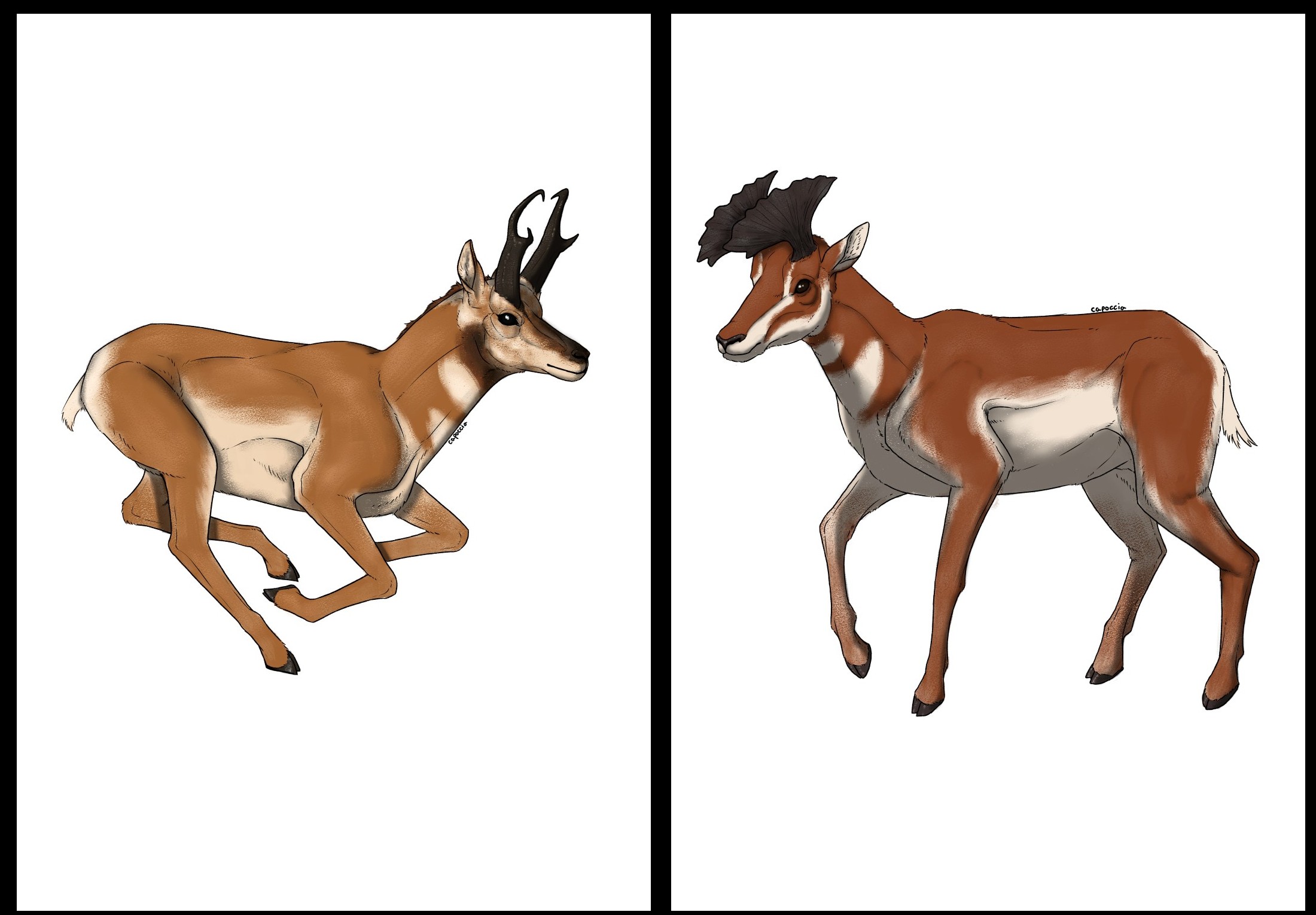

Antilocaprids were once diverse animals in North America. Today, they are represented by a single species: the American bison (Antilocapra americana), one of the fastest herbivores in the world. One of the two subfamilies, Merycodontinae, became extinct about six million years ago. This coincided with the emergence of proboscids, the group of modern elephants that competed with the Merycodontinae for forest environments.

The other subfamily, Antilocaprinae, began to decline about six million years ago, which coincided with an increase in felid diversity. One example is the American cheetah (Miracinonyx), which, like the African cheetah, was adapted for high-speed pursuit.

Studies by other research groups suggest that predation by this species is one evolutionary explanation for the high speed of American antelopes. This study supports that hypothesis by showing that felid diversity may have impacted the past extinction of antilocaprids.

In a previous study, the researchers pointed to the gigantism of herbivores in the Iberian Peninsula as a factor that contributed to the extinction of predators 15 million years ago. This time, the studies cover much larger territories on a continental scale (read more at agencia.fapesp.br/53910).

“The great contribution of this set of studies is precisely to present the idea that the interaction between predators and prey can have an effect on large evolutionary patterns. This had been debated for decades, but there was no really robust set of results to support this hypothesis,” says Mathias Pires, a professor at IB-UNICAMP who supervised the study.

Antilocaprinae (left) have been reduced to a single living species, while Merycodontinae (right) are completely extinct (Illustration: Felipe Capoccia/UNICAMP)

Macroevolution

Both the current and previous studies were only possible due to the substantial amount of data on fossil records from North America and Eurasia, which includes information on body size and diet. These databases are available online for free and allow a variety of estimates to be made.

Armed with the data, the researchers traced the evolutionary history of several groups of large animals. This enabled them to estimate the probable timing of their emergence and extinction, as well as which species coexisted and interacted during the same period.

For example, saber-toothed cats appeared 12 million years ago in North America and 14 million years ago in Eurasia. At their peak, eight species coexisted. Their diversity remained stable until six million years ago, when it began to decline, eventually stabilizing at five species. They became extinct in the Holocene era, which began 11,700 years ago.

The period during which saber-toothed cats declined in diversity coincided with changes that made the climate more arid. This expansion of open environments increased the number of ruminant animals that feed on grasses. Meanwhile, leaf-eating animals lost the forests that provided their food and shelter.

“Our study did not find a direct relationship between this event and the reduction in saber-toothed cats, but these changes in the environment had an indirect impact on the extinctions of different saber-toothed species by reducing the availability of prey,” Pires says.

One group that was adversely affected by these changes was the Merycodontinae. This subfamily of antilocaprids was folivorous and dependent on forests. Eventually, they became extinct. Meanwhile, the grazing antilocaprids – most of the Antilocaprinae at the time – prospered for longer, but they too declined with the increase in felid diversity.

“We’re showing how an increase in predators can reduce the availability of prey, which in turn reduces the abundance of predators, and how this can manifest on an evolutionary scale. It’s a warning about how we may be altering the future with the extinctions we’re causing now,” Pires concludes.

The article “Variation in prey availability over time shaped the extinction dynamics of sabre-toothed cats” can be read at academic.oup.com/jeb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/jeb/voaf043/8115575.

The study “Open ecosystems expansion, competition, and predation shaped the evolution of Antilocapridae” is available to subscribers at academic.oup.com/evolut/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/evolut/qpaf091/8124702.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.