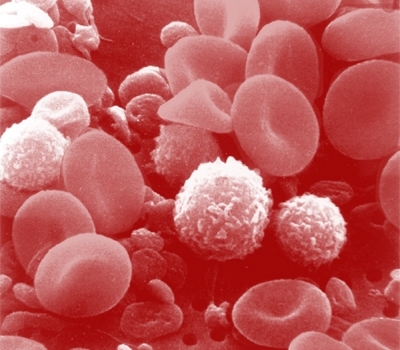

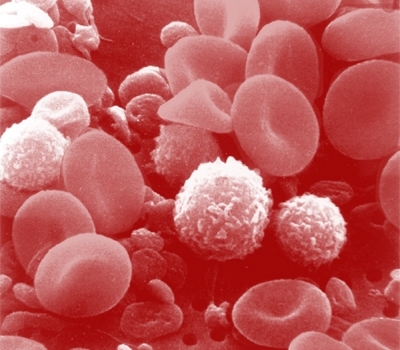

Approximately 0.5% of 40,000 donor blood samples collected in Rio de Janeiro and Recife during the 2012 dengue epidemic were contaminated. No severe cases were found among the subjects infected during transfusion (image: Bruce Wetzel & Harry Schaefer/ National Cancer Institute/ Wikimedia Commons)

Approximately 0.5% of 40,000 donor blood samples collected in Rio de Janeiro and Recife during the 2012 dengue epidemic were contaminated.

Approximately 0.5% of 40,000 donor blood samples collected in Rio de Janeiro and Recife during the 2012 dengue epidemic were contaminated.

Approximately 0.5% of 40,000 donor blood samples collected in Rio de Janeiro and Recife during the 2012 dengue epidemic were contaminated. No severe cases were found among the subjects infected during transfusion (image: Bruce Wetzel & Harry Schaefer/ National Cancer Institute/ Wikimedia Commons)

By Karina Toledo | Agência FAPESP – A study published in March in The Journal of Infectious Diseases shows that, on average, 0.51% of the people who went to two major Brazilian blood banks to donate blood during a dengue epidemic already carried dengue virus, although they displayed no symptoms of the disease during the procedure.

The study also shows that dengue was contracted by 37.5% of the patients who received contaminated blood and were susceptible to the virus because they had not been infected previously, although no severe cases were reported.

“Actually, when we compared the patients infected during transfusion with the control group who didn’t receive contaminated blood, there were no statistically significant differences in mortality or even the incidence of severe symptoms such as fever, nausea, bleeding or low platelet count. These symptoms are common to patients with dengue and transfused patients generally,” said Ester Sabino, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (FM-USP) and director of the same university’s Institute of Tropical Medicine (IMTSP) in Brazil.

The study, which was supported by FAPESP, was conducted in the cities of Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro State) and Recife (Pernambuco State) during the 2012 dengue epidemic. The same group of researchers plan to begin a similar study soon for Zika virus and chikungunya virus.

From February to June 2012, when serotype 4 dengue virus (DENV-4) circulated widely, everyone who gave blood at the Rio de Janeiro and Recife blood banks (Hemorio and Hemope) was invited to participate in the study by donating an extra sample for analysis in search of viral RNA. Samples were given by 39,134 donors. DENV-4 viremia was confirmed in 0.51% of the donations from subjects in Rio de Janeiro and 0.80% of those in Recife.

“In Recife there were weeks when as many as 2% of donations were infected with the virus,” Sabino said.

A total of 42 blood bags contaminated with DENV-4 were transfused to 35 recipients. Of these, 16 were identified as susceptible because they had no markers of recent infection by DENV-4. Six people were actually infected, resulting in a transfusion transmission rate of 37.5%.

Blood samples had also been taken from the recipients before transfusion to determine whether they acquired the virus during the procedure. The recipients were monitored for 30 days following transfusion to watch for any symptoms.

“The study shows that many cases of transfusion transmission occur during major outbreaks of dengue,” Sabino said. “Why had no one ever noticed? Possibly because the clinical impact is not significant.”

However, she added, the final number of contaminated patients was small, and the possibility that severe cases could be detected in a larger population cannot be ruled out.

According to the article, the first cases of dengue virus transmission by transfusion were documented in three recipients in Hong Kong, China, in 2002. Transmission to two recipients was reported in Singapore in 2008. Only one case of dengue hemorrhagic fever in a transfused patient has been identified to date (in Puerto Rico).

Pioneering study

The study was performed in partnership with Brian Custer and Michael Busch from the Blood Systems Research Institute (BSRI) in the United States and was also funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). It is the largest survey of dengue transmission by transfusion conducted anywhere in the world and the first to estimate the transmissibility rate in such cases.

For this reason, the study is highlighted in an editorial commentary in the same journal, written by José Eduardo Levi, Head of the Department of Molecular Biology at Fundação Pró-Sangue, São Paulo’s blood bank.

“Transmission was independent of the donor’s viral load, and, interestingly, all three components usually obtained from blood donations (plasma, red blood cells and platelets) were able to transmit DENV-4,” Levi writes.

Moreover, he says, it is “intriguing that a tiny volume of virus in mosquito saliva injected into the skin can be much more harmful than 200–300 ml of virus in a blood bag from a viremic donor. This suggests that the amount of virus is less important than the form in which it is presented to the immune system. It has been shown that the structure of the viral particle changes according to body temperature, which differs between mosquitoes and humans. In addition, mosquito saliva, the vehicle for the viral particles injected into the skin, has important immunomodulatory and antigenic properties that are absent from the transfusion transmission model.”

Levi also notes that the virus’s “initial replication in keratinocytes and Langerhans cells may provide access to the lymphoid tissue and bone marrow, sites where intense viral replication takes place.”

Preventive measures

The routine followed by Brazilian blood banks currently includes tests to detect AIDS/HIV, hepatitis C (HCV), hepatitis B (HBV), human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV), syphilis (Treponema pallidum bacterium) and Chagas disease (Trypanosoma cruzi protozoa).

According to Sabino, arboviruses such as those that cause dengue, Zika and chikungunya can currently be detected only by molecular tests such as PCR, which are more expensive than serological tests based on the detection of antibodies. There is no consistent evidence to date of a need to screen blood donors for the presence of dengue virus, she believes.

In his editorial, Levi says that, because transfusion-transmitted dengue can cause symptomatic disease, effective prevention measures should be adopted, at least for patients who may be more vulnerable to dengue infection.

The researchers also suggest that viral inactivation may be worth considering in the future to treat all blood donated for transfusion.

“With the popularization of sequencing methods, human beings have been shown to harbor a veritable virome in their bodies,” Sabino said. “Our plasma carries a great many different viruses. Some don’t cause any diseases, but we don’t yet know what others may cause. The viral inactivation techniques available today can be used only in platelets and plasma, not in red blood cells. In addition, they increase the cost of the procedure considerably.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.