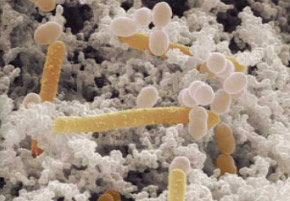

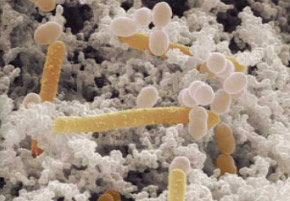

The benefits of the bacterium Bifidobacterium longum are evaluated by Brazilian researchers (photo: Mark Schell/University of Georgia)

The benefits of the bacterium Bifidobacterium longum are evaluated by Brazilian researchers.

The benefits of the bacterium Bifidobacterium longum are evaluated by Brazilian researchers.

The benefits of the bacterium Bifidobacterium longum are evaluated by Brazilian researchers (photo: Mark Schell/University of Georgia)

By Karina Toledo, Caxambu

Agência FAPESP – The results of a study conducted at Universidade de São Paulo (USP) indicate that the consumption of the probiotic Bifidobacterium longum could offer benefits for people suffering from asthma.

In experiments conducted in mice, treatment with the bacterium reduced the quantity of mucous in the lungs and the presence of inflammatory markers typical of this allergic disease that affects airways. Additionally, scientists observed a decrease in bronchial hyperactivity – the exaggerated contraction of the smooth muscles in the bronchioles that characterizes asthma.

The preliminary results of the FAPESP-funded study were presented during the 28th annual meeting of the Federation of Experimental Biology Societies (FeSBE), which was held from August 21 to 24 in Caxambu, Minas Gerais.

“Our hypothesis is that acetate, a short-chain fatty acid produced in large quantities by the species Bifidobacterium longum (BL), is responsible for reducing allergic inflammation,” said Caroline Marcantonio Ferreira, a researcher at the USP Institute of Biomedical Sciences and coordinator of the study.

According to Ferreira, probiotics are microorganisms that, when ingested live and in adequate quantities, can promote health benefits.

“The data in the scientific literature indicate that, to be defined as a probiotic, there must be between 107 and 109 colony forming units per gram or per milliliter. In very small quantities, the microorganisms cannot colonize the intestine and generate the benefits,” she stated.

Ferreira explained that the use of probiotics has been recommended since the 19th century. Some time ago, the objective was solely to promote local benefits, such as the regulation of the intestine and fighting chronic inflammatory disease.

“In the last five years, however, studies have begun to indicate the beneficial effects of probiotics in distant organs, such as the lung or the brain. Although there are studies showing that the intestinal microbiota influences this behavior, there are still several gaps, and these relationships must be better studied. We are attempting to discover the effect of probiotics on asthma,” she explained.

For the experiment, the animals were split into six groups. The first, considered a control group, received only a placebo and did not undergo a procedure for asthma induction.

In the second group, asthma was induced, and the animals were treated only with a placebo. The third group received treatment only with the BL probiotic. The fourth group only received treatment with another type of probiotic called Bifidobacterium adolescentis (BA), which also produces acetate but in lower quantities. The fifth group was treated with BL and underwent asthma induction. The sixth group was treated with BA and underwent asthma induction.

“The utilization of probiotic bacteria that produce different quantities of acetate allowed for the evaluation of the importance of this substance - and the quantity necessary - to prevent asthma,” said the researcher.

Treatment with the two types of probiotics began two weeks before the procedure that induced allergic inflammation similar to asthma in animals. The bacteria were administered directly through the esophagus through a method known as gavage.

“Mice do not naturally have asthma, but there are several ways to induce the disease to create an experimental model. We used the traditional method, which is to administer an egg protein known as ovalbumin, an allergen to rodents,” explained Ferreira.

At first, ovalbumin was systemically administered twice in an interval of 7 days to promote the sensitivity of the immunological system. After an interval of 14 to 21 days, the protein was again administered in the lung. “The defense cells, already heightened, acted quickly and triggered allergic inflammation at the site,” stated Ferreira.

During the allergy induction period, the treatment with probiotics continued. At the end of the experiment, the researchers compared various inflammatory markers in the different groups.

The analysis of the airways showed that 90% of the cells in the control group were macrophages. In the untreated asthmatic animals, between 60% and 70% of the cells found in the sample were eosinophils, which are considered asthma markers.

In the BL group, the proportion of eosinophils was reduced by half, falling to between 20% and 30% of cells. In the animals treated with BA, the scientists observed a smaller reduction of this marker, to between 40% and 45% of cells.

A sample of the pulmonary tissues was extracted for a histological analysis to measure the presence of mucous. The asthmatic group treated with BL presented similar results to the control group – which means that the probiotic almost completely inhibited mucous production. The group treated with BA showed results similar to the asthma-induced group treated with a placebo: 80% of the cells were covered in mucous.

Lastly, in a lung function test, the researchers observed that the BL treatment reduced bronchial hyper-reactivity. However, the treatment with BA did not change this parameter.

Modulating the biological system

In another experiment, the asthmatic animals were treated solely with acetate using two different protocols, and the results were even more promising than treatment with probiotics.

“In the first group, we administered acetate systemically through daily intraperitoneal injections. For the other group, the acetate was placed in water. Apparently, administration in water was even more efficient; because acetate is ingested every time the animal drinks the liquid, the level of acetate in the organism is maintained throughout the day. However, we need to repeat the experiment to confirm this with certainty,” said Ferreira.

The researcher’s hypothesis is that acetate acts through a receptor called GPR43, which is expressed in the dendritic cells of the immune system.

“When the receptor is activated in the cells, a process that is still not very well understood, the Th2 inflammatory response is inhibited in the airways,” she explained.

The next step, according to Ferreira, is to treat asthmatic mice with dead B. longum bacteria. The objective is to verify whether the benefit of the probiotic is related to a substance produced by the microorganism or whether the mere presence of the bacterium is capable of modulating the immune system.

“To definitively prove that the benefit is related to acetate, we would have to produce bacteria that are genetically modified not to produce this substance. This will be very great challenge,” said Ferreira.

The opposite could also be attempted if the relationship between acetate and lowered inflammation is proven,” Ferreira said. “We could genetically modify bacteria to produce more acetate, which in theory, would make the treatment more efficient. This is the approach for probiotic studies: discovering how they act and for which diseases they can offer benefits,” commented Ferreira.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.