Uýra Sodoma, a biologist, visual artist, and ecology master’s degree holder, spoke at the seminar on “Amazonia,” narrated from both a traditional and scientific perspective (photo: Heitor Shimizu/Agência FAPESP)

Researchers, institution leaders, and representatives of indigenous communities discuss the importance of natural history museums and their role in the 21st century at a symposium during FAPESP Week France.

Researchers, institution leaders, and representatives of indigenous communities discuss the importance of natural history museums and their role in the 21st century at a symposium during FAPESP Week France.

Uýra Sodoma, a biologist, visual artist, and ecology master’s degree holder, spoke at the seminar on “Amazonia,” narrated from both a traditional and scientific perspective (photo: Heitor Shimizu/Agência FAPESP)

By Heitor Shimizu, from Paris | Agência FAPESP – The France-Brazil Museology Seminar, held on June 12th and 13th in Paris, brought together researchers, institutional leaders, and representatives of indigenous communities to discuss the importance of natural history museums and their role in the 21st century.

The event was organized by the National Museum of Natural History (MNHN) in partnership with FAPESP and the University of São Paulo (USP). It was part of the program for FAPESP Week France 2025.

“Natural history museums date back to the 17th century in Europe, when plants, animals, and artifacts from other continents were collected around the world and sent to European centers to stock the so-called ‘cabinets of curiosities,’ which were highly prized by the nobility. Some of these cabinets became the basis for what would become large collections, such as those of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris and the British Museum in London. This period, from the 17th to the 20th century, was particularly marked by European domination of the world, later followed by the neocolonial expansion of other powers,” said Eduardo Neves, Director of the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at the University of São Paulo (MAE-USP).

Eduardo Neves (MAE-USP): museums can contribute to the inclusion of scientific knowledge within a broader spectrum of knowledge (photo: Heitor Shimizu/Agência FAPESP)

“By bringing together archaeological, anthropological, geological, zoological, and botanical collections, museums can promote a more holistic understanding of the ‘natural’ world and humanity’s place in it. This integration encourages collaboration between disciplines, allowing researchers to address complex issues that require knowledge from different fields – such as understanding biodiversity loss, tracking interactions between humans and the environment, or studying the Earth’s geological and ecological transformations. In addition, this approach allows for the incorporation of other perspectives beyond those derived exclusively from scientific research,” said Neves.

He argues that this multidisciplinary and multicultural approach not only aligns with the interconnected realities of the 21st century, but also repositions natural history museums as vital spaces for research, education, and dialogue with the public.

“Through their own transformation, museums can contribute to the emergence of new discourses and narratives that insert scientific knowledge not only into cultural and historical perspectives but also into a broader spectrum of knowledge, based on other categories and experiences beyond those defined by the scientific system,” said Neves.

Horizontal dialogues

Uýra Sodoma, a biologist, visual artist, and arts educator, spoke at the seminar on “Amazonia, narrated from a perspective that’s both traditional and scientific, with the aim of reoccupying a more dignified, truer, and more current place in the eyes of worlds that still perceive us as they did five centuries ago.”

Uýra, who has a master’s degree in ecology, explained that her work addresses biodiversity from “a perspective of this place called Amazonia, mixing science with art. Our work, as indigenous contemporary artists, is to create debates that are relevant to the present time – a time that’s never existed before. We’re insisting on dialogue as indigenous people, using art as a path, insisting on important dialogues, using art as a good trap to capture the curious, as Jaider Esbell, a Makuxi indigenous artist and a reference in contemporary art, used to say.”

“Indigenous people from worlds that have never been heard, always violated, use art, beauty, magic, and all their knowledge to capture the curiosity of people who approach this art saying, ‘How cool! How beautiful!’ But there’s a lack of dialogue, a lack of conversation, which is what we need to have between the indigenous worlds and the Western worlds,” said Uýra, showing a photo from a book in her presentation with the caption “Theodor Koch-Grünberg writing down stories from an indigenous person on his trip from 1911 to 1913.” The German ethnologist is identified, but the other person is not. He is simply “an indigenous person.”

“When we look at images like these, with one person’s name and the other unnamed, we understand that this should be described as a dialogue because there are two people facing each other. But we know that, for centuries, there were no real horizontal dialogues with respect, without interest in the extraction, in the exploitation of knowledge, skills, artifacts, minerals, flora, fauna – or even heads, as in the Weltmuseum in Vienna, which displays a human head from the Munduruku people,” she said.

“Today, we have the opportunity to create a dialogue in which no one is above anyone else, in which one side doesn’t steal everything the other has. A dialogue in which we understand that difference no longer needs to be a reason for violence. It’s in difference that we must build the dialogues of our time. It’s in real respect, in listening, in co-authorship,” said Uýra.

Knowledge deposits

“Museums in general, but here in our case natural history museums, are safe havens where scientific information is transmitted to society. This becomes even more important at this moment in our history, when the narrative – that is, who tells the story and how they tell it – often takes on more relevance than the scientific facts themselves or science itself,” said Luís Fábio Silveira, Deputy Director of the USP Museum of Zoology.

He argues that museums occupy a privileged position as spaces of public trust where people seek quality information, which is essential in times of scientific denialism and disputes over the role of science and scientists.

“Today, we’re in an unequal competition with cell phone screens. People want quick and easy information, often without the necessary depth, where the narrator matters more than the content conveyed,” said Silveira, displaying a symbolic image of a group of teenagers engrossed in their cell phones with their backs to Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch” at the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands.

Luís Fábio Silveira of the Museum of Zoology at USP warned of the decline in the collection of specimens for scientific collections (photo: Heitor Shimizu/Agência FAPESP)

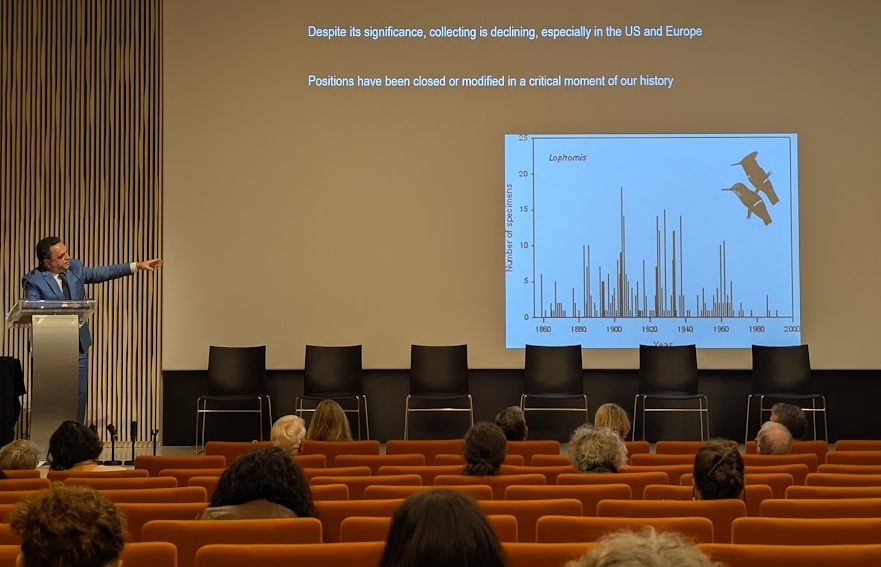

Silveira also warned about a concerning trend: the decline in the collection of specimens for scientific collections, particularly in countries in the Northern Hemisphere.

“Science fundamentally depends on museum collections. Bioengineering, medicine, ecology, and many other fields benefit from preserved specimens. However, we’ve seen a sharp decline in collections, particularly in North America and Europe. A clear example is hummingbirds: until the 1940s, thousands of specimens were collected regularly. Since the 1980s – and even more so since the 2000s – virtually no new specimens have been added to the world’s major collections,” he said.

This depletion of collections has been accompanied by institutional changes. “There’s been a significant reduction in the number of curators. Instead of scientists or specialists dedicated to maintaining and expanding collections, many museums have relied solely on technicians. This compromises the ability of these institutions to monitor and interpret changes in biodiversity, precisely at a time of global ecological crisis,” he said.

Silveira argues that natural history museums are more than just exhibition spaces. “They’re guardians of time. They bring together the planet’s biodiversity – botanical, microbiological, fungal, zoological – and preserve specimens that would otherwise disappear from the face of the Earth. It’s these collections that allow us to establish baselines for understanding current and future transformations. They’re living archives, essential for predicting what’s to come.”

“Artifacts and specimens kept in natural history museums have defied time. They’ve only reached us because they were preserved in these institutions. This is the irreplaceable role of museums – to withstand the test of time and enable us to understand and face the changes that mark our present and will shape our future,” he said.

For more news and information about FAPESP Week France, visit: fapesp.br/week/2025/france.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.