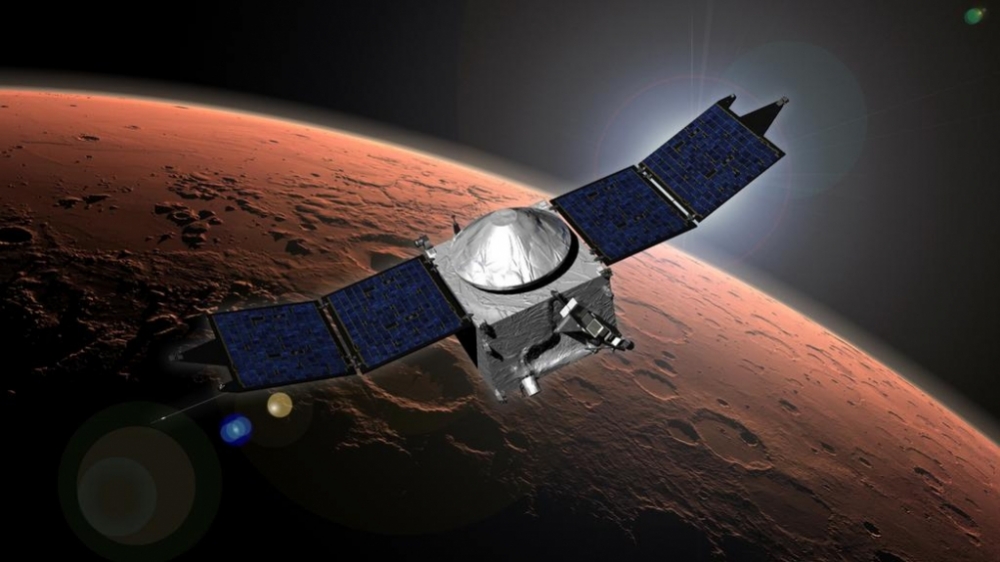

Planets with high atmospheric chemical disequilibrium are expected to be the principal targets for space missions, say members of the space agency’s Astrobiology Institute at a meeting in Brazil (image of the MAVEN space probe: NASA)

Planets with high atmospheric chemical disequilibrium are expected to be the principal targets for space missions, say members of the space agency's Astrobiology Institute at a meeting in Brazil.

Planets with high atmospheric chemical disequilibrium are expected to be the principal targets for space missions, say members of the space agency's Astrobiology Institute at a meeting in Brazil.

Planets with high atmospheric chemical disequilibrium are expected to be the principal targets for space missions, say members of the space agency’s Astrobiology Institute at a meeting in Brazil (image of the MAVEN space probe: NASA)

By Elton Alisson

Agência FAPESP – On September 21, 2014, the space probe MAVEN [Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution], operated by the U.S. space agency NASA, successfully entered Mars’ orbit for a special scientific mission: to understand how the atmosphere and climate of the red planet change over time.

Two days later, on September 23, the Indian space agency (ISRO) announced that its satellite Mangalyaan is also orbiting Mars to try to measure the presence of methane in the planet’s atmosphere.

The measurements being carried out by the two probes for the next 6-12 months are eagerly awaited by an international group of researchers, which includes Brazilians, dedicated to studying the origin and evolution of life on Earth and other planets. This group focuses on thermodynamics, disequilibrium and evolution (TDE) at NASA’s Astrobiology Institute.

Members of the group, established in 2010, met for the first time in Brazil on September 24-25, 2014 on the occasion of the 7th International Workshop on Thermodynamics, Disequilibrium and Evolution at the Brazilian Center for Research in Energy and Materials (CNPEM) in Campinas.

“Our group’s goal is to try to fill in the gaps between researchers who work on experimental theoretical aspects regarding the origin of life and astronomers in the field of remote sensing who plan space missions in order to define targets of the search for extraterrestrial life,” said Eugenio Simoncini, post-doctoral fellow at the Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory of the National Astrophysics Institute (INAF) in Italy and TDE vice president, at the event’s opening session.

According to Simoncini, the search for planets that are suited to harboring life should be directed towards those that present high atmospheric chemical disequilibrium, as is the case for Mars.

Atmospheric chemical disequilibrium, one of the conditions required for the existence of life on a planet, is characterized by the simultaneous presence of different quantities of reagent gases such as oxygen, hydrogen and methane in the planetary atmosphere, Simoncini explained.

“It’s important to study this state of atmospheric chemical disequilibrium because of the potential role it plays in detecting life on other planets,” he said.

More than 1,000 extra-solar planets have already been discovered. “We need to reduce the selection of planets that are [potentially] inhabited to those that present high chemical disequilibrium related to no other process such as photosynthesis but life,” Simoncini said during a lecture at the event.

Chemical traces

On September 24, 2014, in an article published in the journal Nature, an international group of astronomers announced that, for the first time, they had detected steam in the atmosphere of the extra-solar planet HAT-P-11b, which is similar in size to the planet Neptune.

This was not the first time chemical evidence related to life was found. In 2005, the Mars Express Probe of the European Space Station (ESA) detected the presence of methane on the Martian surface. The discovery caused great fanfare in the astronomic community because on Earth, methane is mainly produced by biological processes such as the decomposition of organic matter. The presence of methane on Mars could be a sign that gas-producing organisms live on the planet.

The expectations of this discovery suffered a setback, however, after NASA’s Curiosity probe revealed in September 2013 that the amount of methane gas in Mars’ atmosphere is much less than originally thought.

Now, with the entry of the MAVEN and Mangalyaan probes in Mars’ orbit, additional data about the composition and history of the planet’s atmosphere and how these have influenced conditions for the existence of life are expected to be obtained.

“The existence of methane on Mars could indicate the presence of life or an active geological process,” said Douglas Galante, a researcher at the National Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNLS) of the CNPEM and member of the TDE.

“Somehow, this chemical disequilibrium on Mars that we are studying in the TDE shows that despite appearing dry, the planet is in some way alive, perhaps not with life as we know it but with active geological processes,” he said.

The TDE researchers have long been developing a methodology to calculate and compare the chemical disequilibrium on planets in an effort to identify evidence of life in the Universe.

Based on a computer modeling system for astrophysical simulations developed by Italian astronomers, this group of scientists is conducting thermodynamic analyses (of the causes and effects of temperature, pressure and volume changes in a system) to assess how life affects the geochemical processes on Earth and verifying whether other planetary atmospheres are inhabitable or present similar chemical disequilibria.

“All knowledge based on experimental and observational data about how life on Earth came about and evolved can be adapted so that we can look for life on other planets, like Mars,” Galante said. “It does us no good to send space probes to a planet if we don’t know which indicators, molecules and chemical disequilibria they need to find.”

Brazilian astrobiology

The meeting in Campinas was the seventh meeting held by the astrobiology research group. Previous meetings have taken place in Europe and the United States, and the next is expected to be held in Tokyo, Japan.

The idea to hold this meeting in Brazil was to add Brazilian researchers in the field to the TDE group and to strengthen ties with the NASA Astrobiology Institute, which began in December 2011 on the occasion of the São Paulo Advanced School of Astrobiology – Making Connections Spasa2011.

Promoted under the scope of the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences (SPSAS) – a FAPESP funding mechanism, the event brought together 160 researchers, faculty members and students from Brazil and abroad.

“Through this latest event, we sought to recover and strengthen the interaction that began with the NASA Astrobiology Institute on the occasion of the São Paulo Advanced School of Astrobiology held three years ago with FAPESP support,” Galante said.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.