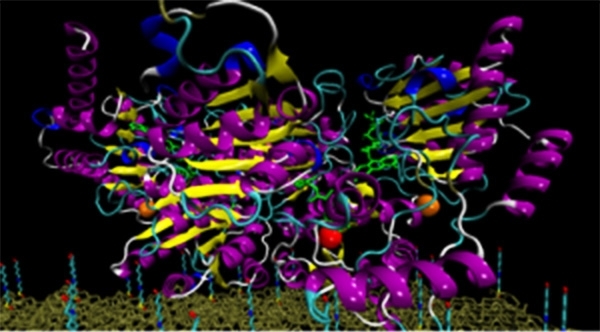

Representation of an enzyme (upper part of image) fixed to the tip of an atomic force microscope capturing herbicide molecules on a surface (lower part of image) (image: GNN/UFSCar)

A nanobiosensor developed at a Brazilian university is being tested for use in detecting target molecules typical of nervous system diseases.

A nanobiosensor developed at a Brazilian university is being tested for use in detecting target molecules typical of nervous system diseases.

Representation of an enzyme (upper part of image) fixed to the tip of an atomic force microscope capturing herbicide molecules on a surface (lower part of image) (image: GNN/UFSCar)

By José Tadeu Arantes

Agência FAPESP – The early diagnosis of certain types of cancer, as well as nervous system diseases such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica, may soon be facilitated by the use of a new detection device: a nanometric sensor capable of identifying biomarkers of these pathological conditions.

The nanobiosensor was developed at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), Sorocaba, in partnership with the São Paulo Federal Institute of Education, Science & Technology (IFSP), Itapetininga, São Paulo State, Brazil. It was originally designed to detect herbicides, heavy metals and other pollutants. An article about the nanobiosensor has just been published as a cover feature by IEEE Sensors Journal.

“It’s a highly sensitive device, which we developed in collaboration with Alberto Luís Dario Moreau, a professor at IFSP. We were able to increase sensitivity dramatically by going down to the nanometric scale,” said physicist Fábio de Lima Leite, a professor at UFSCar and the coordinator of the research group.

The nanobiosensor consists of a silicon nitride (Si3N4) or silicon (Si) nanoprobe with a molecular-scale elastic constant and a nanotip coupled to an enzyme, protein or other molecule.

When this molecule touches a target of interest, such as an antibody or antigen, the probe bends as the two molecules adhere. The deflection is detected and measured by the device, enabling scientists to identify the target.

“We started by detecting herbicides and heavy metals,” Leite told Agência FAPESP. “Now we’re testing the device for use in detecting target molecules typical of nervous system diseases, in partnership with colleagues at leading centers of research on demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system, such as Doralina Guimarães Brum Souza at UNESP Botucatu, Paulo Diniz da Gama at PUC Sorocaba, and Charles Peter Tilbery at Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo.”

He began the research five years ago with a grant from FAPESP under its Young Investigators Grants program, continuing after that as the coordinator of UFSCar’s Nanoneurobiophysics Research Group (GNN).

The migration from herbicide detection to antibody detection was motivated mainly by the difficulty of diagnosing demyelinating diseases, cancer and other chronic diseases before they have advanced beyond an initial stage.

The criteria for establishing a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica are clinical (supplemented by MRI scans), and patients do not always present with a characteristic clinical picture. More precise diagnosis entails ruling out several other diseases.

“The development of nanodevices will be of assistance in identifying these diseases and reducing the chances of false diagnosis,” Leite said.

Biomarkers

The procedure can be as simple as placing a drop of the patient’s cerebrospinal fluid on a glass slide and observing its interaction with the nanobiosensor.

“If the interaction is low, we’ll be able to rule out multiple sclerosis with great confidence,” Leite said. “High interaction will indicate that the person is very likely to have the disease.” In this case, further testing would be required to exclude the possibility of a false positive.

This simplicity is confined to the general principle, however. In practice, the device will be more complicated to operate because of its sensitivity, requiring a highly controlled environment shielded from vibration and contamination.

“Different nervous system diseases have highly similar symptoms. Multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica are just two examples. Even specialists experience difficulties or take a long time to diagnose them. Our technique would provide a differential diagnostic tool,” Leite said.

Leite’s research team for this project includes three graduate students, all with scholarships from FAPESP: Pâmela Soto Garcia, Jéssica Cristiane Magalhães Ierich, and Adriano Moraes Amarante.

The next step for the group, according to Leite, is to research biomarkers for these diseases that have not been completely mapped, including antibodies and antigens, among others.

“Our group has begun tests for the detection of head and neck cancer, in partnership with André Lopes Carvalho at the Barretos Cancer Hospital and Osvaldo Novais de Oliveira Jr. at the São Carlos Physics Institute,” Leite said. “The experiments, conducted by postdoc scholar Nadja Karolina Leonel Wiziack, use the nanobiosensors we developed and an electronic device developed by Professor Oliveira Jr.’s group.”

The article “A Nanobiosensor Based on 4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate Dioxygenase Enzyme for Mesotrione Detection” by Fábio de Lima Leite et al. can by read at http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=6960059.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.