Marine bioindicators help in environmental impact analyses

Study shows that the level of heavy metals in organisms living in marine sediment was slightly higher in submarine outfall than that found in seawater.

Marine bioindicators help in environmental impact analyses

Study shows that the level of heavy metals in organisms living in marine sediment was slightly higher in submarine outfall than that found in seawater.

Study shows that the level of heavy metals in organisms living in marine sediment was slightly higher in submarine outfall than that found in seawater

By Flora Serra

Agência FAPESP – Summer time: think vacations and trips to the beach. To determine which beaches are safe for swimming and which are polluted, environmental agencies perform hydrochemical analyses along the entire Brazilian coastline. And a study carried out at the Geosciences Institute in the Universidade de São Paulo (USP) School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities shows the importance of conducting a geochemical analysis of sediment and of studying marine bioindicators as part of environmental impact analyses when evaluating beach water quality.

The study, which was

funded by FAPESP, was coordinated by Professor Wânia Duleba and sought to evaluate the environmental quality of the water and sediment in distinct localities: the Araçá and Almirante Barroso Maritime Terminal (Tebar) submarine outfalls.

“These two regions are located in São Sebastião, on the São Paulo State coastline and receive sewage effluent. Araçá receives domestic sewage, and Tebar receives industrial, or petrochemical, sewage,” said Duleba.

The comparative study evaluated the influence of two types of effluents in the marine environment. The analyses went beyond the hydrochemical aspects of the sites.

The researchers determined the geochemical characteristics of the marine sediment (or sea floor) and analyzed how the biota (the set of living creatures at the site) reacts to the presence of different types of components in the water.

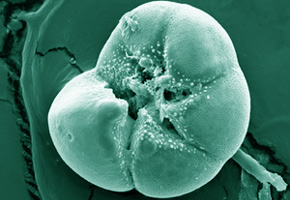

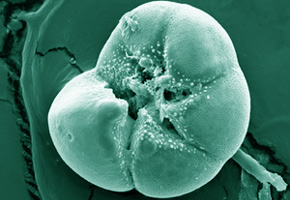

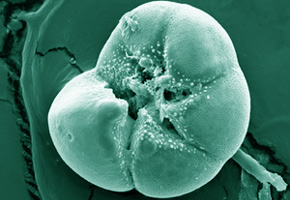

The living organism chosen to carry out the analysis was an opportunistic species of benthic foraminifera, Ammonia tepida. “This is a protozoan that has a limestone carapace and inhabits the sea floor, where it absorbs the chemical elements that are occasionally deposited in the ocean,” said Duleba.

Collection of the foraminifers was performed during different seasons of the years 2005, 2006 and 2007. Soon after, the still-living protozoans’ carapaces were chemically analyzed using mass spectrometry.

Duleba stresses the importance of carrying out analyses on living organisms. “Environmental studies in the past usually made observations of dead organisms. However, our study showed that they must be analyzed while still living because, when they die, they no longer reflect their state at the time of collection,” she said.

Metal in carapaces

The researchers also took into consideration soil gradation and geochemical analyses of the sediment obtained from the Geosciences Institute, as well as hydrochemical data from the water column provided by the São Paulo State Water Quality Authority (CETESB). They found a peak in copper contamination at the Tebar outfall during the second half of 2006.

“A strong presence of copper was found in the carapaces of the foraminifers collected during the period studied. In 2005/2006, the foraminifers were smaller in size, their numbers on the sea floor were small, and the biodiversity in the area was diminished, all of which indicate a possibly anomalous situation,” said Duleba.

The chemical elements found in the carapaces were determined by mass spectrometry at the University of Bremen in Germany and by X-ray fluorescence using the synchrotron light source at the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory in Campinas.

Duleba notes that the water at the evaluated marine site did not exceed the pollutant limits allowed by environmental agencies in the other periods analyzed. From the data, “we can’t draw a conclusion about whether the water column in São Sebastião, which is subject to intense spillage from the Araçá and Tebar outfalls, is contaminated,” she said.

However, when comparing the hydrochemical variations provided by CETESB with those from the sediment and its biota, the researchers found that the presence of some chemical components was greater in the foraminifers’ carapaces than in the water.

“In environmental impact studies, it’s not effective to analyze only the water in a marine region. The sediment must be considered, mainly the benthic biota at the site. Environmental agencies should pay attention to this factor,” affirmed Duleba.