The evolution of microorganisms comprises 85% of biological history, according to Andrew Knoll during the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences on Evolution

The evolution of microorganisms comprises 85% of biological history, according to Andrew Knoll during the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences on Evolution

The evolution of microorganisms comprises 85% of biological history, according to Andrew Knoll during the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences on Evolution

The evolution of microorganisms comprises 85% of biological history, according to Andrew Knoll during the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences on Evolution

By Karina Toledo

Agência FAPESP – “Imagine your favorite landscape but without any sort of plants or animals,” said Andrew Knoll, professor of Natural History at Harvard University, in explaining the state of Earth three billion years ago.

“The temperature was like a summer day in Rio de Janeiro, and there was practically zero oxygen. We would not have survived for more than three minutes on the planet,” Knoll affirmed. According to the scientist, the environment may have seemed sterile at first sight, but life was fully active. Microorganisms were already performing photosynthesis and fixing nitrogen from the atmosphere in the form of compounds that would be the nutrients for other living beings in the future.

Knoll was in Brazil to participate in the 1st São Paulo School of Advanced Science – Evolution (SPSAS-Evo), which was held on Ilhabela through August 31st. The event was part of the São Paulo School of Advanced Science (ESPCA), an FAPESP-funded program offering short courses in advanced research in different areas of study. It was also promoted by the universities of São Paulo (USP), Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP) and Estadual Paulista (UNESP).

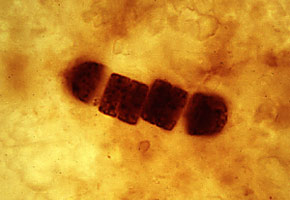

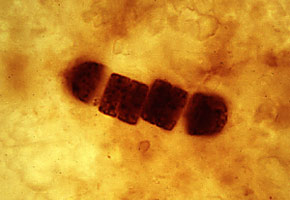

In his presentation, the researcher highlighted that 85% of the history of life on Earth is microbial. “When we think of the fossil record, we first think of dinosaurs. However, they only appeared 200 million years ago. Animals, in general, are 600 million years old at the most. However, the geological records show that Earth is 4.5 billion years old and only became a biological planet at least 3.5 billion years ago,” Knoll stated.

Through the chemical analysis of fossils and stones collected in western Australia and the southern part of Africa, Knoll and his team reconstructed the planet’s environmental history. “Then, we used physiology to connect this knowledge with the biological history,” Knoll told Agência FAPESP.

The large deposits of iron in the Earth’s subsoil are evidence that the planet’s first inhabitants used this element to breathe, together with sulfur and carbon. “The chemical composition of the sediments show that before 2.4 billion years ago, there was no oxygen in the atmosphere,” he explained.

The scenario began to change with the advent of cyanobacteria, the first group of microorganisms able to use sunlight, water and carbon dioxide (CO2) to photosynthesize and produce oxygen, thus enabling the formation of the ozone layer and allowing the appearance of eukaryotic organisms with their highly specialized ‘energy factories’ known as mitochondria.

“I always note to students that the Earth is not a silent platform upon which evolution occurs. Life influences the way the environment changes, and in turn, the environment influences the course of evolution,” said Knoll.

Primary producers

Another great watershed in biological history was the appearance of the angiosperms, the flowering, fruit-producing plants, affirmed professor Susana Magallón from the Universidade Nacional Autônoma de México’s Botany Department, who also participated in SPSAS-Evo.

“The angiosperms are the primary producers in an ecological chain. This means that they are the basis of all of the existing ecosystems in existence today. According to some theories, many animal species co-evolved with the angiosperms, including pollinating insects, birds and bats,” Magallón said.

In addition to this, added Magallón, recent studies suggest that even such ancient plant species as ferns began to diversify once again in response to the new habitats created by the angiosperms, thus giving rise to more modern subspecies.

“Angiosperms have a complex stem system capable of forming dense crowns and a variety of trees. This allows for much richer forests than those composed mostly of conifers, and different types of organisms prosper in the niches they find,” Magallón explained.

Magallón calculates that angiosperms began diversifying between 130 and 140 million years ago, an estimation based on the analysis of the fossil record and techniques known as molecular clocks.

“We measured the number of genetic differences between the current strains and their ancestral strains preserved in the fossil record. This allowed us to estimate the time that separates the species,” Magallón explained.

However, the evolution rate of each species must be known in order for these molecular clocks to be well calibrated. “Some groups undergo a molecular substitution every year, yet ten years can pass for other species. The time scale has to be homogenized to be able to make comparisons,” said Magallón.

During her presentation, Magallón spoke about how to evaluate the quality of fossil records to decide whether they can be used in the calibration of molecular clocks, a subject to which she has dedicated herself for the last ten years.

More recently, the researcher has been investigating the evolutionary processes behind the enormous diversity of plants found in the northern part of the neotropical ecozone, comprising southern Mexico, southern Florida and all of Central and South America.

“To this end, we compared the rate of species generation with the extinction rate. The evolutionary processes behind the diversity found in Mexico are undoubtedly different than those that occurred in the Amazon or the Brazilian Cerrado, and they are also less well known,” she evaluated.

Read more about SPSAS-Evo at: www.ib.usp.br/zoologia/evolution

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.