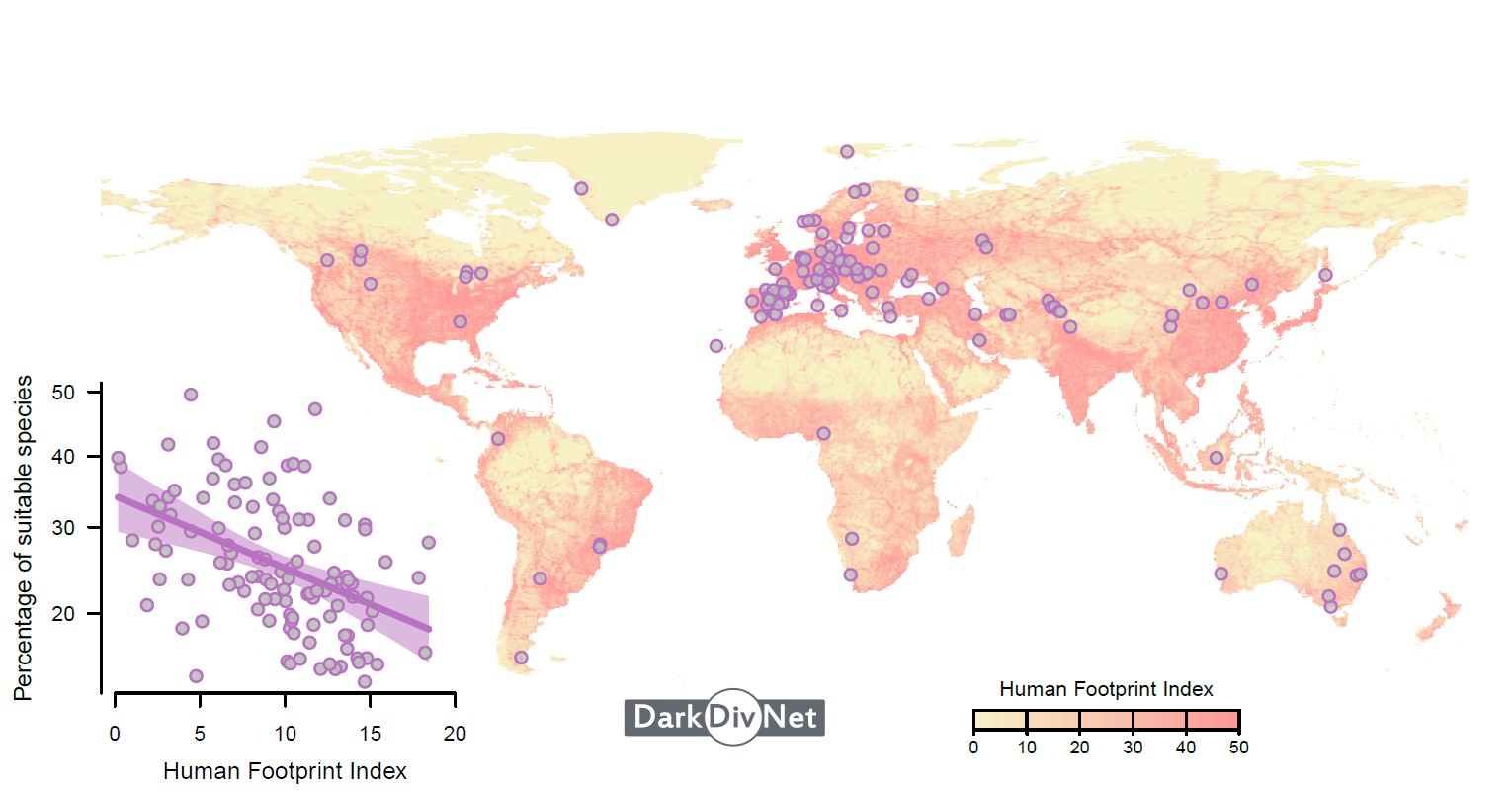

Map of the regions studied, scatterplot (credit: DarkDivNet)

A survey of 119 regions around the world investigated “missing diversity,” or native species that could be present in a given area but were absent. The results were published in the journal Nature.

A survey of 119 regions around the world investigated “missing diversity,” or native species that could be present in a given area but were absent. The results were published in the journal Nature.

Map of the regions studied, scatterplot (credit: DarkDivNet)

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – Natural vegetation often lacks many species that could be present but are not. This occurs mainly in regions heavily affected by human activity. A study published in the journal Nature conducted an exhaustive survey of this phenomenon in 119 regions around the world. The article reports on what experts call “dark diversity,” which can be understood as “missing diversity.”

Over 200 researchers from the international DarkDivNet collaboration participated in the study, investigating the presence or absence of plants in 5,500 locations. The research was coordinated by Professor Meelis Pärtel from the Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences at the University of Tartu in Estonia. It also involved Alessandra Fidelis and Mariana Dairel, among other Brazilians.

“In each location, local researchers recorded all plant species and identified the missing diversity, that is, native species that could live there but were absent. This allowed us to understand the potential plant diversity in the area and also to measure the impact of human activities on natural vegetation,” explains Fidelis, a professor at the Institute of Biosciences at the São Paulo State University’s (IB-UNESP) Rio Claro campus.

Area subjected to anthropic impact near the Itirapina Ecological Station in the state of São Paulo (photo: Mariana Dairel)

According to the study, ecosystems in regions with little human impact typically contain more than one-third of potentially suitable species. The absence of the remaining two-thirds is due to natural factors, such as limited dispersal. However, in regions heavily impacted by human activities, ecosystems contain only one-fifth of suitable species. “Traditional measures of biodiversity, such as simply counting the number of species present, don’t detect this impact, as the natural variation in biodiversity between regions and ecosystems hides the true extent of human influence,” say the study’s coordinators.

According to Professor Meelis Pärtel, the DarkDivNet collaboration began about seven years ago, in 2018. “We’d introduced the theory of dark diversity and developed methods to study it, but to make global comparisons, we needed consistent sampling across many regions. It seemed like an impossible task, but many colleagues from different continents joined us,” he says. Despite the difficulties arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and global economic and political crises, data were collected over the years, even without central funding.

Fidelis joined the study from the beginning, when a small DarkDivNet meeting was held at the International Association for Vegetation Science (IAVS) conference in Bozeman, United States, in 2018. “After that, several researchers joined the initiative, applying the same methodology in different locations around the world. Dr. Mariana Dairel, who was my doctoral student at the time, was excited about the idea and helped me collect the data. We decided to gather information in the Itirapina region, in the state of São Paulo, where the Itirapina Ecological and Experimental Stations are located. In this region, there’s both native Cerrado [Brazilian savanna-like biome] vegetation and anthropized areas with pine and eucalyptus plantations,” says the researcher.

He adds: “We know that human impact has had several consequences for ecosystems, affecting biodiversity. However, this study goes further: it shows how we’re losing not only the species that were there before, but also those that could potentially be in the area, thus affecting natural regeneration.”

Ecological footprint

The level of anthropogenic disturbance in each region was measured using the Human Footprint Index, which includes factors such as human population density, changes in land use (e.g., urbanization and agriculture), and infrastructure (e.g., roads and railways). The study found that plant diversity in a location is negatively affected by its “ecological footprint.” The higher the index, the lower the diversity. Anthropogenic influence can extend hundreds of kilometers from the point of origin.

“This result is alarming because it shows that human disturbances have a much broader impact than previously thought, even reaching nature reserves. Pollution, deforestation, littering, trampling, and fires caused by humans can exclude plants from their habitats and prevent recolonization. We also found that the negative influence of human activity was less pronounced when at least one-third of the surrounding area remained intact, which reinforces the global goal of protecting 30% of the Earth’s land area by 2030,” says Professor Pärtel. He emphasizes the importance of maintaining and improving the health of ecosystems beyond nature reserves and suggests using the concept of “missing diversity” as a practical tool for conservation and restoration activities.

The study’s authors attribute the impoverishment of vegetation to fragmentation, loss of connectivity, defaunation (loss of animal species, especially seed dispersers), disturbances such as fire and timber extraction, and eutrophication (a form of pollution that occurs when nutrients increase in bodies of water, such as rivers, lakes, and estuaries). The presence of at least 30% natural landscape was associated with mitigating these effects.

Alessandra Fidelis received support from FAPESP through the project “How Does Fire Season Affect Cerrado Vegetation?”. Mariana Dairel received a Ph.D. scholarship from FAPESP.

The article “Global impoverishment of natural vegetation revealed by dark diversity” can be accessed at www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-08814-5.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.