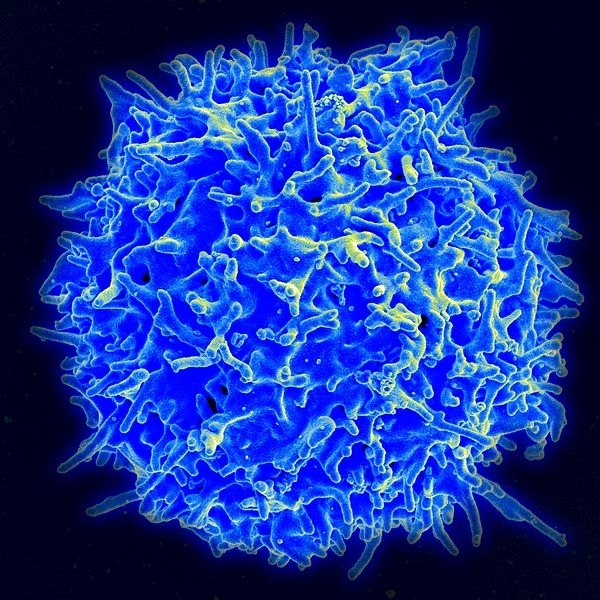

Researchers found differences in rates at which some immune cells proliferate (image: Wikimedia Commons)

Experiment shows that cryopreservation alters rate of apoptosis and lymphocyte proliferation in patients with this autoimmune disease.

Experiment shows that cryopreservation alters rate of apoptosis and lymphocyte proliferation in patients with this autoimmune disease.

Researchers found differences in rates at which some immune cells proliferate (image: Wikimedia Commons)

By Karina Toledo

Agência FAPESP – Deep-freezing samples of blood cells from volunteers for future analysis is common practice in clinical trials but may bias the results of studies in patients with lupus, according to an experiment performed at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) in Brazil.

When the researchers compared fresh and frozen blood samples from patients with this autoimmune disease, they found differences in the proliferation rate of TCD4 lymphocytes, which are cells of the immune system.

“Data in the scientific literature suggest that the lymphocytes of lupus patients are more fragile and display an increased tendency toward apoptosis, i.e., programmed cell death. Our hypothesis is that the weakest cells died during cryopreservation and that this introduced a positive selection bias. Only the strongest cells proliferated after thawing, which explains why the rate was higher than in fresh samples,” said Luis Eduardo Coelho Andrade, Head of UNIFESP’s Immunology & Rheumatology Laboratory.

With FAPESP’s support, Andrade is coordinating a project designed to investigate the functioning of TCD4 lymphocytes, and especially subtypes Th1, Th2, and Th17 and regulatory T cells (Tregs), in lupus patients.

Lupus, which has no known cause, is a chronic disease in which the immune system attacks healthy tissue. The most common targets are the skin, joints, kidneys and brain, but other organs may also be affected.

“There are protocols for freezing and thawing blood samples very slowly so as not to damage them,” Andrade said. “However, regardless of how much care is taken, the cells are full of water, and ice crystals form inside them. Some functions may be altered. We wanted to see how cryopreservation affects Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells and Tregs.”

Blood samples were taken from 20 lupus patients and 18 healthy volunteers paired by sex and age. Some of the samples from each group were frozen. The rest were used immediately in apoptosis and cell proliferation assays.

“Cryopreservation increased the rate of lymphocyte apoptosis in both healthy volunteers and lupus patients. However, the increase in apoptosis was far more evident in the cells of lupus patients,” Andrade said.

Curiously, while cryopreservation also increased the rate at which Th2 and Th17 cells and Tregs proliferated in lupus patients, Th1 cells in frozen blood samples from lupus patients proliferated at the same rate as Th1 cells in fresh blood. In the case of healthy volunteers, only Th1 cells proliferated at a higher rate as a result of cryopreservation.

“We believe that the lymphocytes, which are known to be weaker in lupus patients, died during freezing and that only the strongest cells remained in the samples when thawed. The fresh samples, however, contained both more viable cells and damaged cells that couldn’t proliferate,” Andrade said.

The results, which will soon be published in the journal Cryobiology, show that cryopreservation has a significant impact on blood cells and that this impact is different in the cells of people with and without lupus.

“This explains part of the controversy found in the literature on functional studies with cells from lupus patients,” Andrade said. “We know that some studies used fresh blood samples, while others used frozen samples.”

For Andrade, cryopreserved samples should not be used in research on lupus. “It may be that this positive selection bias is actually desired in a given experiment, but scientists must be aware of this factor when designing experiments,” he said.

Differences in serum

In another arm of UNIFESP’s project, experiments were performed to test a theory proposed in previous studies: that the blood serum of lupus patients contains factors that stimulate lymphocyte apoptosis.

“The number of circulating lymphocytes is often below normal in lupus patients,” Andrade said. “When you isolate these cells and start working with them in the lab, you find that they’re already degenerating and are sensitive to any procedure. Thus, we set out to understand why this happens.”

The researchers collected serum from 23 lupus patients and from the same number of healthy volunteers paired by sex and age.

“We created a pool of lupus serum and a pool of healthy serum. Then, we took lymphocytes from each individual and placed them in culture medium containing each type of serum to measure the rates of apoptosis,” Andrade said.

When undifferentiated TCD4 lymphocytes were incubated with serum from healthy individuals, the rate of apoptosis was 1.8%. When the cells were incubated with serum from lupus patients, the rate was 5.5%. This threefold increase was observed for lymphocytes from both lupus patients and healthy individuals.

However, in the case of lymphocytes differentiated into the subtypes Th1, Th2, and Th17 and into Tregs, the lupus serum did not increase the rate of apoptosis. “The results suggest that the blood serum of lupus patients contains some factor that induces lymphocyte apoptosis but doesn’t affect differentiated cells. Our next step is to identify the molecules in the serum that are responsible for this effect,” Andrade said.

Imbalance

In a third arm of the project, the group led by Andrade evaluated the distribution of the different types of lymphocytes in blood and urine samples from patients with lupus nephritis, one of the most serious manifestations of the disease, which potentially leads to kidney failure and death.

With the help of a flow cytometer, which differentiates between cell types present in solution based on immunofluorescence, the group measured the proportions of effector cells (Th1, Th2 and Th17), which stimulate inflammation, and regulatory cells (Tregs), which play an immunosuppressive role.

The results were described in articles published in the Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research and the Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology.

“Our analysis of the blood samples showed that the frequency of Tregs in lupus (1.4%) is similar to the normal frequency (1.1%). However, the ratio of effector T cells in lupus (10.8%) is higher than the normal ratio (6.1%). In other words, there is an imbalance in the ratio of effector cells to regulatory cells in lupus, which probably favors the autoimmune response observed in this disease,” Andrade said.

In addition to quantitative differences, the experiment showed higher expression of functional molecules by lupus patients’ effector lymphocytes, which were more active than those taken from healthy volunteers.

The researchers found that the higher the level of Th1 cells in the urine of patients with lupus nephritis was, the lower the level of Th1 cells in their blood. This inverse correlation was not observed in patients with other kinds of kidney disease. The researchers also found a strong tendency for the urine of lupus nephritis patients to have reduced Treg levels. According to Andrade, this finding can serve as a biomarker when measuring kidney tissue inflammation.

“The inflammatory process occurs not in blood but in kidney tissue, and the urine theoretically expresses what’s happening in the kidney,” he said. “Thus, if I observe a large infiltrate of Th1 cells in the kidney tissue, I’d expect to see a larger amount in the urine than in the peripheral blood. In contrast, when the inflammatory process is less intense in tissue, the proportion of Th1 cells in the blood will be higher.”

Currently, the group is standardizing an immunocytochemical test to observe the frequency of each lymphocyte subtype in tissue collected by kidney biopsy. Immunocytochemistry is a laboratory technique that uses antibodies to identify cells.

“We expect the results to reflect what we observed in urine,” Andrade said. “If so, we’ll be much more confident about this line of reasoning.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.