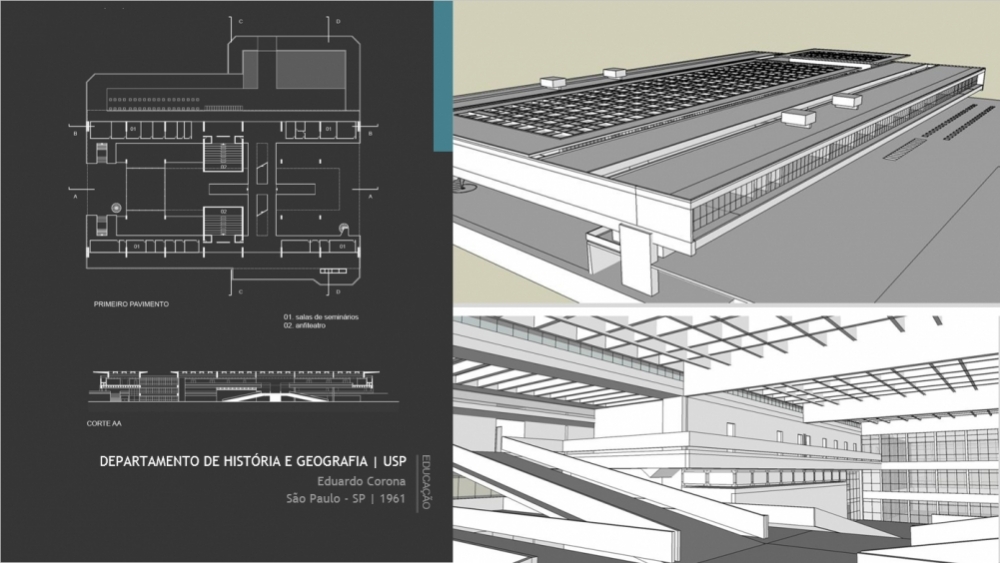

Floor plan and elevations for the History & Geography building at the University of São Paulo, designed by Eduardo Corona in 1961 (image: presentation document for project "Diffusion of Modern Architecture in Brazil")

The 1959-1963 Carvalho Pinto Administration Action Plan promoted the construction of over 1,000 public buildings and amenities.

The 1959-1963 Carvalho Pinto Administration Action Plan promoted the construction of over 1,000 public buildings and amenities.

Floor plan and elevations for the History & Geography building at the University of São Paulo, designed by Eduardo Corona in 1961 (image: presentation document for project "Diffusion of Modern Architecture in Brazil")

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – The inauguration of Brasília on April 21, 1960, associated Brazil with modernity. It was the culmination of a reinvention of the urban landscape that gathered momentum in the 1940s and 1950s.

In São Paulo State, however, public buildings remained out of step with the new trend until 1959. The Department of Public Works (DOP), subordinated to the state government, had produced eclectic designs for a long period. Meanwhile, the powerful Department of Agriculture, which was in charge of its own buildings, preferred neocolonial architecture as well as eclecticism.

The situation changed significantly under Carlos Alberto de Carvalho Pinto (1910-1987), who governed São Paulo State from January 31, 1959, to January 31, 1963. He presided over the construction of more than 1,000 new public buildings with modern architectural designs, as well as the refurbishment and extension of existing buildings.

“Many of the buildings begun in the period are paradigmatic works of modernist architecture, such as the School of Architecture & Urbanism at the University of São Paulo (USP), and the Departments of History and Geography,” said architect Miguel Antonio Buzzar, a professor at USP’s São Carlos Institute of Architecture & Urbanism (IAU-USP), in an interview with Agência FAPESP.

Buzzar was principal investigator for the project “The diffusion of modern architecture in Brazil: the architectural heritage created by the 1959-1963 Carvalho Pinto Administration Action Plan (PAGE)”, supported by FAPESP. The project involved more than 20 researchers, including Monica Camargo Junqueira and Maria Tereza Regina Leme de Barros Cordido.

“During the project, we inventoried 602 buildings out of an estimated 1,000 or more, surveying 511 of them in considerable detail,” Buzzar said.

This building boom gave rise to what is known as the “São Paulo school of architecture”, giving prominence to the names of João Batista Vilanova Artigas (1915-1985), Paulo Archias Mendes da Rocha (b. 1928), Carlos Millan (1927-1964), and many others. It was an outcome of the State Government Action Plan, known locally by the acronym PAGE. The plan was drafted, approved and implemented by the Carvalho Pinto administration.

“PAGE wasn’t just about buildings,” Buzzar said. “It also called for bridges and other infrastructure, including water supply networks, sewerage, electricity and roads throughout São Paulo State, creating a public service network. We identified PAGE-related public works in 265 municipalities all over the state.”

Hydropower and the university’s first campus

The state government built colleges, schools, courthouses, health centers, farm co-ops, etc., and construction of the Urubupungá hydroelectric power plant began thanks to PAGE, which also called for extensions or improvements to the Limoeiro, Euclides da Cunha, Barra Bonita, Jurumirim, Bariri, Graminha and Xavantes hydro developments.

However, the plan’s impact was wider and more lasting than can be measured in cubic meters of concrete and bricks. For example, it launched the construction of USP’s Armando Sales de Oliveira Campus in the state capital, which was essential for the transformation of the rudiments of a higher education institution into a genuine university. It was also responsible for making FAPESP, which had been on the drawing board since 1947, a reality.

“A fund for the construction of the Armando de Salles Oliveira Campus (FCCUASO) was set up under PAGE. This was later renamed FUNDUSP and is now known as USP’s Physical Facilities Office (SEF),” Buzzar said. “In fact, the action plan established several funds for different purposes, including the State School Building Fund (FECE), later converted into CONESP and more recently into the School Development Fund (FDE).”

PAGE was the Carvalho Pinto administration’s response to an acute economic crisis. Instead of the public spending cuts required by the most conservative economists, the plan followed the formula recommended by John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) to address the Great Depression in the United States: Keynes called for government spending on a massive program of public works, which would create jobs, expand demand, rebuild consumer confidence and reinvigorate the economy.

“The state government had a cash pile in the shape of its pension fund, IPESP [Instituto de Previdência do Estado de São Paulo], so it was able to finance all the public works called for by PAGE without issuing more debt. More than 160 architects were hired to design buildings for the action plan,” Buzzar said.

A passage from the plan clearly reflects the underlying Keynesian approach, he noted: “improvements in community welfare derive from investment in sectors not subject to automatic market mechanisms, such as education, culture, research, healthcare, social work, justice, law enforcement, and sewerage.”

Economics & Humanism

In addition to Keynesianism, another school of thought was even more influential in contributing to the ideas that underpinned PAGE: the Catholic renewal led by Louis-Joseph Lebret (1897-1966), a French Dominican philosopher priest. “PAGE was inspired by Lebret’s Economics & Humanism movement, which was a major influence on the education of young Catholic militants in Brazil and on its Christian Democrats,” Buzzar said.

After working for a long time with fishing communities in Brittany, northern France, Lebret launched the Economics & Humanism movement in the 1940s as a sort of third way between capitalism and socialism. He later visited some 60 countries, including Brazil, where he lived and worked for several years. Together with a group of followers he led research on living conditions in the poor neighborhoods of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte and Recife, training professionals to work with local government. Later, he played a key role in the Second Vatican Council and took part in the drafting of the constitution Gaudium et spes (“Joy and Hope”) and the encyclical Populorum progressio (“On the Development of Peoples”), issued by Pope Paul VI (1897-1978).

Carvalho Pinto was a conservative from a well-established family. His ancestors were big coffee planters in São Paulo State, and his great-uncle Francisco de Paula Rodrigues Alves was President of Brazil from 1902 to 1906. Nevertheless, as a Christian Democrat, he was deeply interested in Lebret’s ideas, and he appointed Plínio de Arruda Sampaio (1930-2014), another Christian Democrat and a Catholic militant, to head the drafting and manage the implementation of PAGE. At that time, Sampaio, who was to have an important political career in later years, including a far-left presidential bid in 2010, was an enthusiast follower of Lebret and of Economics & Humanism.

“Plínio brought the state government and modernist architects together,” Buzzar recalled. “One of the tenets of Lebret’s humanist economics was that public amenities such as schools, hospitals, health centers, etc. should be used to promote social reforms. And Sampaio saw the formal qualities of modernist architecture as a symbolic representation of this principle. Some of the key features of the architecture of the period are large free spans and no walls around buildings, so they were open to their surroundings to allow free access by the general public. They were designed to be genuinely public facilities and to form a continuum with the external public space rather than being cut off from it. Some buildings surrounded public squares, which invited active life to come inside. Not all buildings produced under the action plan were like this, but this was the paradigm for the buildings considered most representative of the architecture typical of PAGE.”

Sampaio organized an agreement with the Institute of Brazilian Architects (IAB), whose leaders then included João Batista Vilanova Artigas. The new buildings and other public amenities were designed by firms of architects and mostly built by small firms rather than major contractors, which were only to become linchpins of Brazil’s economic structure under the military-civilian dictatorship. To avoid cronyism and to level the playing field, budgets and contracts were debated and voted on in fully minuted meetings held at the IAB. “There was an unofficial alliance between the government and the architects affiliated with the IAB,” Buzzar said. “It wasn’t clearly formulated, but it enabled a substantial proportion of these architects to put into practice their ideals regarding the social function of architecture. This is what the São Paulo school was all about.”

As well as Artigas, Mendes da Rocha and Millan, a large group of modernist architects designed amenities and buildings for PAGE, including Abrahão Sanovicz, David Libeskind, Eduardo Corona, Eduardo Kneese de Mello, Icaro Castro Mello, Joaquim Guedes, José Maria Gandolfo, Maurício Nogueira Lima, Pedro Paulo de Melo Saraiva, Rino Levi, Salvador Candia, Ubirajara Gilioli and Victor Reif.

“One of the goals set by PAGE was completion of the Armando Sales de Oliveira Campus, where there were then only a few buildings,” Buzzar said. “Many new buildings were begun under the Carvalho Pinto administration, especially the School of Architecture & Urbanism (FAU) designed by Artigas, the History and Geography building designed by Corona, and the CRUSP residential building designed by Kneese de Mello. But these are only some of the iconic buildings of the period. In our study we selected 163 buildings across the state for their architectural importance. They represent the plurality of modernist languages then in use and are worthy of conservation.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.