Brain coral (Mussismilia hispida), whose skeleton is composed of calcium carbonate, retains carbon in mineralized form, which helps to mitigate the greenhouse effect (photo: Guilherme Henrique Pereira Filho/LABECMar/UNIFESP Archive)

A single species found in the Alcatrazes Archipelago, brain coral, produces around 170 tons of calcium carbonate annually. This represents the retention of approximately 20 tons of carbon in mineral form, which can last for centuries or millennia. A study by the Federal University of São Paulo highlights the potential ecosystem services provided by subtropical corals.

A single species found in the Alcatrazes Archipelago, brain coral, produces around 170 tons of calcium carbonate annually. This represents the retention of approximately 20 tons of carbon in mineral form, which can last for centuries or millennia. A study by the Federal University of São Paulo highlights the potential ecosystem services provided by subtropical corals.

Brain coral (Mussismilia hispida), whose skeleton is composed of calcium carbonate, retains carbon in mineralized form, which helps to mitigate the greenhouse effect (photo: Guilherme Henrique Pereira Filho/LABECMar/UNIFESP Archive)

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – The population of one species of coral in the main island of the Alcatrazes Archipelago Wildlife Refuge (REVIS), located off the northern coast of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, retains about 20 tons of carbon per year. This amount is equivalent to the carbon emissions from burning 324,000 liters of gasoline. These results come from a study published in the journal Marine Environmental Research by researchers supported by FAPESP at the Institute of Marine Science of the Federal University of São Paulo (IMar-UNIFESP) in Santos.

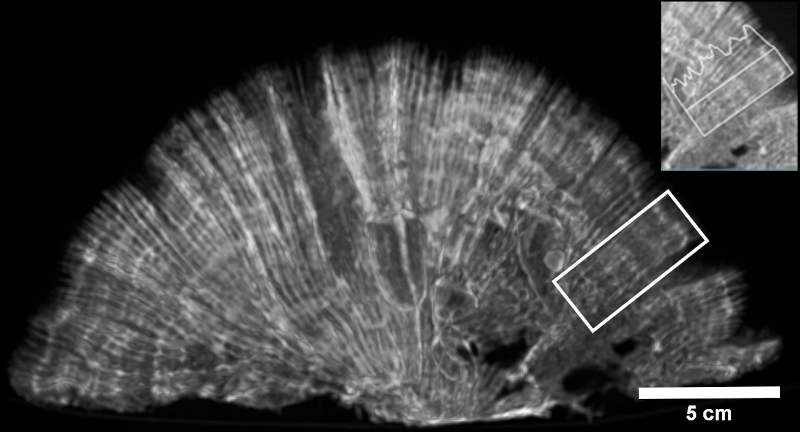

The authors analyzed specimens of brain coral (Mussismilia hispida), whose skeleton is mainly composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Using computed tomography images, the researchers calculated the annual growth rate of the colonies. They then estimated the production of 170 tons of CaCO3 per year.

Calcium carbonate is composed of the elements calcium, oxygen, and carbon. The latter is also found bound to oxygen, forming carbon dioxide (CO2), which contributes to the greenhouse effect when released into the atmosphere as a result of the burning of fossil fuels.

“We wanted to understand the growth of brain coral, but it’s very difficult to cut the skeleton in a way that allows this measurement to be made. So we did CT scans, in which it’s possible to observe the so-called annual growth bands. With this data, accumulated between 2018 and 2023, it was possible to estimate the production of calcium carbonate and, consequently, how much carbon they store and prevent from being released into the atmosphere each year,” says Luiz de Souza Oliveira, first author of the study. Oliveira conducted the study as part of his master’s degree in the Graduate Program in Biodiversity and Marine Ecology at UNIFESP.

Tomography images allow the growth of brain coral to be estimated through growth bands, which represent one year of life (photo: Guilherme Henrique Pereira Filho/LABECMar/UNIFESP Archive)

However, to determine the total calcium carbonate production of all brain coral colonies in the archipelago, the researchers first needed to determine the area occupied by the species on the seabed. This is where Mônica Andrade da Silva, a co-author of the study, comes in. As part of her master’s degree at the same institution, she conducted this study using sonographic techniques to map the seabed with a scholarship from FAPESP.

“The growth rate of the corals was higher than we expected, similar to that of corals in tropical regions. This was a surprise because subtropical corals are considered marginal, living at the limit of their optimal conditions in this part of the South Atlantic and, in theory, they should grow less,” explains Guilherme Henrique Pereira Filho, coordinator of the Marine Ecology and Conservation Laboratory (LABECMar) at IMar-UNIFESP. He supervised the study and recently had a new project approved by FAPESP to study another type of formation on the São Paulo coast.

Tropical coral reefs, such as those in Abrolhos and Fernando de Noronha, have similar calcium carbonate production rates to those found in the area studied by the authors. However, it is not yet known why the corals in Alcatrazes do not accumulate to form reefs around the islands.

One hypothesis is that the corals arrived in the subtropical region relatively recently, between 2,000 and 3,000 years ago, and therefore have not had enough time to form larger structures. Another possible explanation is the higher incidence of storms in the region, which destroy coral colonies periodically and prevent large accumulations that could form reefs.

Sources or sinks?

The study reveals that carbon sequestration may be another important ecosystem service provided by the Alcatrazes Archipelago Wildlife Refuge, as the marine conservation unit is called. The most well-known is the protection of species, many of which are valuable for fishing.

Calculating the carbon captured in Alcatrazes is a first step toward understanding the role of subtropical coral reefs in the global carbon balance. Tropical corals, which are more exposed to light and warmer waters, can emit more carbon than they absorb due to the high respiration rate of the organisms living there.

However, the fact that they do not form large reefs and that their rocky portions are largely covered by macroalgae that absorb CO₂ through photosynthesis may cause subtropical environments, such as Alcatrazes, to be greenhouse gas sinks, absorbing more carbon than they emit.

Additionally, corals store carbon in a mineralized form that can last for centuries or millennia. This contrasts with the organic carbon generated by photosynthesis, which is quickly reintegrated into the atmosphere through the respiration of living beings and the decomposition of organic matter.

The work of the UNIFESP group also shows that, in addition to corals, calcium carbonate is present in large quantities in the sediments of the main island of Alcatrazes. The residue from the breakdown of both coral skeletons and the structures of other organisms, such as mollusk shells, is deposited on the seabed and can remain there for centuries or even millennia.

The Alcatrazes Archipelago is a protected marine area that contributes to species conservation and potentially to carbon capture (photo: Leo Francini)

“Society tends to value an area like Alcatrazes mostly for what it’s protecting from fishing. However, this environment may be providing another essential service in a context where tons of carbon are emitted every day through the burning of fossil fuels,” says Pereira Filho.

The study is part of the Alcatrazes Sea Project, a partnership between UNIFESP, the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio, linked to the Ministry of the Environment), and Petrobras.

The article “Calcium carbonate production by the massive coral Mussismilia hispida in subtropical reefs of the Southwestern Atlantic” can be read at www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0141113625002752.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.