Studies conducted by Brazilian researchers and published in PLOS ONE and Scientific Reports also found compounds derived from Brazilian plants to be promising against hepatitis C (image: PLOS ONE)

Studies conducted by Brazilian researchers and published in PLOS ONE and Scientific Reports also found compounds derived from Brazilian plants to be promising against hepatitis C.

Studies conducted by Brazilian researchers and published in PLOS ONE and Scientific Reports also found compounds derived from Brazilian plants to be promising against hepatitis C.

Studies conducted by Brazilian researchers and published in PLOS ONE and Scientific Reports also found compounds derived from Brazilian plants to be promising against hepatitis C (image: PLOS ONE)

By Peter Moon | Agência FAPESP – Hepatitis C is the main cause of cirrhosis and hence of liver transplants in Brazil, according to the Ministry of Health. Some 50% of liver transplants in São Paulo State are performed on hepatitis B or C patients, according to the state’s health department. Hepatitis C patients alone account for 40% of all liver transplants in São Paulo.

In addition, the therapies available for treatment of hepatitis C patients are expensive, have adverse side effects, and entail viral resistance. Owing to all these issues, studies are needed to develop more efficient antiviral therapies against the disease.

Compounds isolated from animal venom have shown activity against some viruses, such as dengue, yellow fever and measles. Following this line of research, Brazilian scientists affiliated with São Paulo State University (UNESP), the Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU) and the University of São Paulo (USP) have published two articles in which they describe promising results for compounds that combat hepatitis C virus.

The first experiment, with results published in PLOS ONE, tested the antiviral properties of three compounds isolated from the venom of Crotalus durissus terrificus, the South American rattlesnake.

The research was conducted at UNESP’s Institute of Biosciences, Letters & Exact Sciences (IBILCE) in São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo State, by the Virology Group at the Genomic Studies Laboratory, led by Professor Paula Rahal, and at the Virology Laboratory of UFU’s Institute of Biomedical Sciences (ICBIM), led by Professor Ana Carolina Gomes Jardim. FAPESP provided funding of various types, as did the National Council for Scientific & Technological Development (CNPq), the Minas Gerais State Agency for Research and Development (FAPEMIG) and the Royal Society’s Newton Fund (UK).

The compounds from rattlesnake venom were isolated at the Toxicology Laboratory of USP’s School of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Ribeirão Preto, led by Professor Suely Vilela Sampaio.

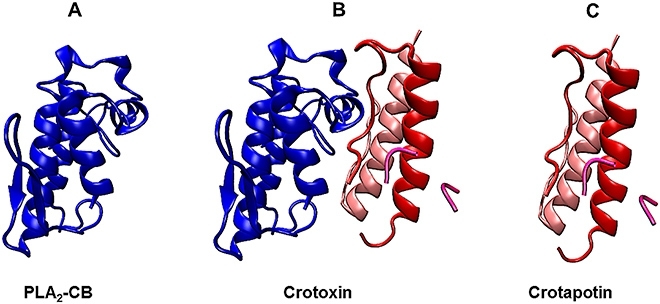

The compounds were phospholipase A2 (PLA2-CB) and crotapotin (CP). In snake venom, they are associated with each other as subunits of the crotoxin protein complex, which the researchers also tested.

In a series of in vitro experiments with cultured human cells, they tested the antiviral action of the two compounds, both separately and together in the protein complex. They observed the compounds’ effects on human cells (to help prevent infection by the virus) and directly on hepatitis C virus.

The hepatitis C virus’s genome consists of a single strand of RNA (ribonucleic acid), which is a simple chain of nucleotides encoding the proteins in the virus.

“This virus invades the human host cell to replicate, producing new viral particles. Inside the host cell, the virus produces a complementary strand of RNA, from which molecules of viral genome will emerge to constitute the new particles,” Gomes Jardim said.

“Our research showed that phospholipase can intercalate into double-stranded RNA, a virus replication intermediate, inhibiting the production of new viral particles. Intercalation reduced these by 86% compared with their production in the absence of phospholipase.”

When the same experiment was performed using crotoxin, production of viral particles fell 58%.

The second stage of the research consisted of verifying whether the compounds blocked the virus’s entry into cultured human cells. In this case, the results were even more satisfactory: phospholipase blocked 97% of viral cell entry, and crotoxin reduced viral infection by 85%.

Lastly they tested crotapotin, another compound isolated from the same rattlesnake’s venom. Crotapotin had no inhibitory effect on viral entry or replication but did affect another stage of the virus’s life cycle, reducing release of new viral particles from cells by 78%. Treatment with crotoxin achieved 50% inhibition of viral release.

According to the researchers, the results of the experiments show that phospholipase and crotapotin produced better results when used separately than together.

Brazilian flora

The second article on the action of chemical compounds against hepatitis C virus describes substances derived not from snake venom but from Brazilian flora. The study, also supported by FAPESP, CNPq, FAPEMIG and the Royal Society’s Newton Fund, was published in Scientific Reports.

The authors tested the antiviral potential of flavonoids from Pterogyne nitens, a tree known in Portuguese as amendoim-bravo. Flavonoids are compounds found in fruit, flowers, vegetables, honey and wine.

The flavonoids tested were sorbifolin and pedalitin. The research was conducted by Professor Luis Octávio Regasini at UNESP’s Green & Medicinal Chemistry Laboratory in São José do Rio Preto.

As with the compounds isolated from rattlesnake venom, the flavonoids were tested for antiviral action in human cells infected with hepatitis C virus and in uninfected cells.

“Sorbifolin blocked viral entry into human cells in 45% of cases, while pedalitin provided more promising results, blocking entry in 79% of cases. The experiment was performed with two genotypes of hepatitis C virus: genotype 2A, the standard type in all studies, and genotype 3, the second most prevalent in Brazil. In both cases, the antiviral action of the flavonoids was equivalent,” Gomes Jardim said.

At the other end of the viral life cycle, the flavonoids had no effect on viral particle replication and did not prevent their release from infected cells.

“The flavonoids from P. nitens are among some 200 tested compounds isolated from Brazilian plants or synthesized using natural structures by Professor Regasini,” Rahal explained.

“These two flavonoids were tested against hepatitis C virus because they’d been shown to have antiviral action in experiments with dengue virus.”

Dengue and hepatitis belong to the same virus family, called Flaviviridae.

The article “Multiple effects of toxins isolated from Crotalus durissus terrificus on the hepatitis C virus life cycle” (doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187857) by Jacqueline Farinha Shimizu, Carina Machado Pereira, Cintia Bittar, Mariana Nogueira Batista, Guilherme Rodrigues Fernandes Campos, Suely da Silva, Adélia Cristina Oliveira Cintra, Carsten Zothner, Mark Harris, Suely Vilela Sampaio, Victor Hugo Aquino, Paula Rahal and Ana Carolina Gomes Jardim can be read at: journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0187857.

The article “Flavonoids from Pterogyne nitens inhibit hepatitis C virus entry” (doi:10.1038/s41598-017-16336-y) by Jacqueline Farinha Shimizu, Caroline Sprengel Lima, Carina Machado Pereira, Cintia Bittar, Mariana Nogueira Batista, Ana Carolina Nazaré, Carlos Roberto Polaquini, Carsten Zothner, Mark Harris, Paula Rahal, Luis Octávio Regasini and Ana Carolina Gomes Jardim can be read at: nature.com/articles/s41598-017-16336-y.

In 2017, the researchers published an article in the Journal of General Virology describing the action of an alkaloid called Fac4 (a synthetic of dibenzoxazepine). This compound also displayed potential against hepatitis C virus, inhibiting viral replication by up to 92% in laboratory tests.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.