Sossina Haile of Caltech has developed a solar reactor supplied by cerium oxide plus zirconium (photo: California Institute of Technology)

Sossina Haile, of Caltech, has developed a solar reactor supplied by cerium oxide plus zirconium.

Sossina Haile, of Caltech, has developed a solar reactor supplied by cerium oxide plus zirconium.

Sossina Haile of Caltech has developed a solar reactor supplied by cerium oxide plus zirconium (photo: California Institute of Technology)

By José Tadeu Arantes

Agência FAPESP – Converting solar energy into fuel that can be stored and suitable for cars is already a reality, at least in the laboratory. The experiment, conducted by Professor Sossina Haile of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in the United States, shows the way to a new path for the production of sustainable energy – one of the greatest current challenges.

A professor of Materials Science and Chemical Engineering at Caltech, Haile presented a report on her experiment at the 6th International Conference on Electroceramics, held from November 9 to 13 in João Pessoa, Paraíba.

Sponsored by the Brazilian Society of Materials Research, FAPESP, National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and the Brazilian Federal Agency for the Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), the event was coordinated by Reginaldo Muccillo, a researcher at the Institute of Energy and Nuclear Research (IPEN); José Arana Varela, full professor at the Ararquara Campus of Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp - Araraquara) and FAPESP CEO; and José Antônio Eiras, associate professor at Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar).

“In order to convert the energy, we utilized ceramic material, cerium oxide (CeO2),” commented Haile behind the scenes at the conference. “When heated at high temperatures, it releases oxygen (O2) without losing its structure. This is pure thermodynamics: maintenance of the state of balance. When it is cooled, it once again absorbs oxygen. If the cooling occurs in the presence of water vapor (H2O) or carbon gas (CO2), the oxygen will be withdrawn from the molecules of one or the other of these substances and the reoxidation will result in the release of hydrogen (H2) in one case or carbon monoxide (CO) in the other, both with great potential as a fuel.”

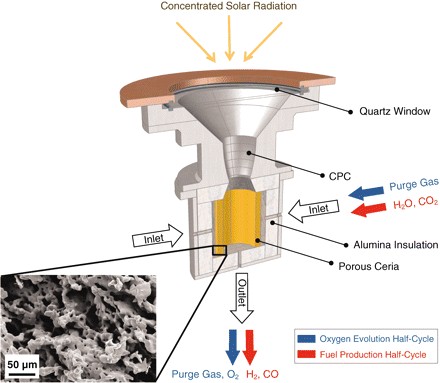

To heat the material, Haile and collaborators utilized a reactor that consisted, in general, of a thermally isolated cavity with a quartz crystal lid that concentrates solar radiation. A single and porous piece of cerium oxide was used to coat the internal cavity.

The oxygen released after heating flows through an exit on the bottom of the recipient. The gases (H2O or CO2) that cool the cerium oxide then enter the cavity, flowing in a radial direction to cross the pores in the material. Through the same exit door, hydrogen or carbon monoxide is ejected after reoxidation [see figure below].

“A specific question that we asked was how to modify the material to increase the efficiency of the process and operate at lower temperatures,” recalled Haile.

The question is very relevant from a technological point of view because reducing the oxide reduction temperature aids significantly in building the reactor. “We verified that by adding zirconium, it is possible to release oxygen at lower temperatures. Instead of operating at 1600 or 1500 degrees Celsius, it is possible to operate at 1450 or 1350 degrees, which is very advantageous.”

“Zirconium makes it possible to lower the temperature because it assists oxygen release from the structure from a thermodynamic point of view. On the other hand, the kinetics of reoxidation later is slower,” noted the researcher. For this reason, several tests were conducted to identify a desirable percentage of zirconium that would favor the temperature and kinetics. “We found that adding 10% to 20% zirconium made it possible to meet both expectations,” she affirmed.

Haile was born in Ethiopia in 1966. Her family was forced to abandon the country in the mid-1970s after a military coup that deposed Haile Selassie. She recalls that her father, a historian, was almost killed by the new faction. In the United States, Haile attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the University of California, Berkeley. Later, with fellowships from the Humboldt and Fulbright foundations, she developed her research at the Max Planck Institut für Festkörperforschung in Stuttgart, Germany.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.