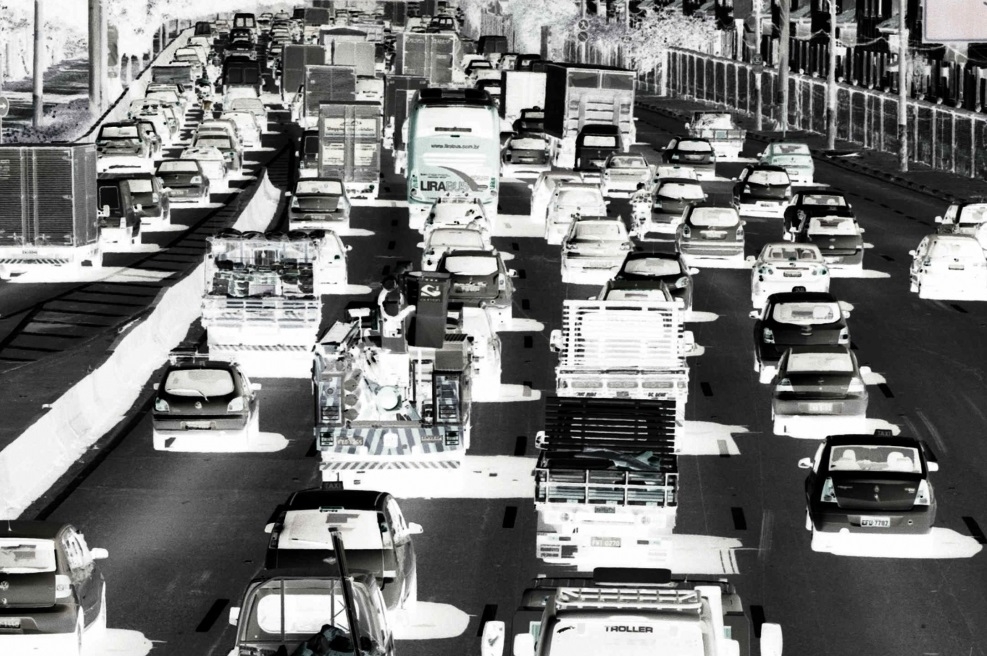

Most cars are licensed in São Paulo City, where the average is 1 car for just under every 2.2 inhabitants (photo: Léo Ramos/FAPESP)

People who live in metropolitan São Paulo take half an hour longer than necessary on average to commute between home and work. Eliminating this excess would add 2.83% to Brazil's GDP.

People who live in metropolitan São Paulo take half an hour longer than necessary on average to commute between home and work. Eliminating this excess would add 2.83% to Brazil's GDP.

Most cars are licensed in São Paulo City, where the average is 1 car for just under every 2.2 inhabitants (photo: Léo Ramos/FAPESP)

By José Tadeu Arantes

Agência FAPESP – How much does it cost you to be stuck in traffic in São Paulo? This question has now been answered with precision. “People who commute by car are spending 100 minutes per day on average in the city’s traffic between home and work,” says economist Eduardo Haddad, Full Professor of Economics at the University of São Paulo’s School of Economics, Administration & Accounting (FEA-USP). “Considering the structural characteristics of metropolitan São Paulo and the mobility patterns found in other Brazilian cities, this commute could be shortened by 30 minutes.”

“The resulting productivity gain would add 2.83% to Brazil’s gross domestic product (GDP), which reached R$5.5 trillion in 2014. In other words, it would add R$156.2 billion to our collective output, and this could translate into extra consumption, corresponding to R$97.6 billion, by the Brazilian population.” Haddad coordinated a research project entitled “Mobility, accessibility and productivity: note on the economic value of commuting time in metropolitan São Paulo”, supported by a regular grant from FAPESP for “Integrated modeling of economic metropolitan systems” and a research scholarship abroad on “Urban economic systems”.

“The main obstacles to obtaining this reduction in commute time and the resulting economic benefit are deep dependence on car use and the huge number of vehicles circulating in the metropolitan area,” Haddad told Agência FAPESP. “This vehicle fleet is too big for the existing traffic infrastructure.” The number of licensed cars totaled 8,357,762 in July 2015, according to the National Traffic Department (DENATRAN).

The population of metropolitan São Paulo totaled 21,090,791 in August 2015, according to IBGE, the national census bureau, so the region has 1 car for every 2.5 inhabitants. Most of these vehicles are licensed in the city proper, where the average is 1 car for just under every 2.2 inhabitants.

For the sake of comparison, it is worth noting that the population of New York City was estimated at 8,491,079 in 2014 by the Department of City Planning. This is almost the same as the number of cars in metropolitan São Paulo.

São Paulo City has 5,267,392 licensed cars, and the number licensed in the other cities of the metropolitan area totals 3,090,370. “The population of São Paulo City grew 6.6% in the past decade, while the number of passenger cars rose 48.2%. In the same period, the city’s traffic infrastructure remained practically unchanged in terms of streets, bridges and so on. The result is evidently drastic overcrowding. The number of passenger cars per square kilometer in the city rose from 3,765 in 2005 to 5,579 in 2015,” Haddad said.

Rush hours

Traffic gridlock is worst during the morning and evening rush hours, when most people are commuting. According to the latest census (IBGE, 2010), 6.36 million people were doing paid work in São Paulo City at the time, and almost 1 million of these lived outside the city. Meanwhile, 170,000 people who lived in the city earned their daily bread elsewhere.

“In most of the metropolitan area’s subregions, the supply of jobs is smaller than the active-age population,” Haddad said. “The main exception is the so-called expanded inner city, as the area between the expressways along the Tietê and Pinheiros rivers is known. With over 1 million surplus jobs, the expanded inner city is the main employment basin for the metropolitan area and hence the focal point for daily commuting. The streets linking the expanded center with other areas are congested and suffer from gridlock as a result.”

São Paulo City actually has a third rush hour: many workers use their lunch break to manage personal affairs, and automotive traffic increases significantly in the middle of the day because so many of them use a car for this purpose.

According to a 2014 report by the Toronto Region Board of Trade in Canada, the average daily commute time in São Paulo exceeds the averages for Tokyo, New York, London, Paris and Madrid but is slightly less than that in Shanghai. Mexico City ranks lowest on this score, with an average daily commute time of 142 minutes, but it is relevant to note that 4 million people commute from other Mexican cities every day to work in the nation’s capital, which is four times the number for São Paulo.

The research project coordinated by Haddad set out to quantify the economic impact of traffic congestion in metropolitan São Paulo. “We first established the structural characteristics of the metropolitan area, considering data such as the area of the territory, urbanized area, population size, income levels, house prices in the various subregions, number and density of jobs, average wage, etc.,” Haddad explained. “We then used this structure as a basis for estimating the average commute time we could consider ‘normal,’ which was about 70 minutes. The actual time was about half an hour longer than this predicted value, reaching some 100 minutes. In technical jargon, this difference is due to what is known as excessive mobility friction.”

Mobility friction

The next step consisted of calculating the effects of excessive mobility friction on worker productivity, with workers being defined as everyone who performs paid work outside the home, and estimating the benefit of its elimination in terms of productivity gains, GDP growth and additional consumer spending.

“We know longer commute times mean lower productivity because people tend to get to work later and leave earlier,” Haddad said. “Moreover, they’re already tired when they start work because of the effort expended to deal with heavy traffic.”

All this is fairly self-evident. However, another factor is less visible and may be even more important. “Shorter commute times lead to a denser labor market because there are more potential workers at a given distance from each workplace. This translates into one of the beneficial effects of clustering, known as agglomeration economies, meaning that people looking for work have more chances of finding the kind of job they prefer, and firms have more opportunities to hire the kind of people they need,” Haddad said.

Shorter commute times increase the choices of both workers and employers, assisting both sides of the labor market, and productivity trends up as a result.

“Our calculations show that shortening the average commute time by half an hour would increase productivity by 15.7% on average,” Haddad said. “The full range of productivity gains would be from 12.6% to 18.9%, in fact, depending on the distance between home and work. This higher productivity in turn would drive a national GDP increase of 2.83% and a corresponding rise in consumer spending propensity.

“São Paulo City would absorb about 50% of these benefits, with municipal GDP potentially expanding by 10.94%. The impact on the metropolitan area as a whole would be an increase of 12.89% in regional GDP and 18.53% in consumption by its inhabitants.”

Large-scale model integration

Haddad’s research project used a technique known as large-scale model integration. Three models were involved: a trip-demand model combining information on commuters’ origins and destinations with physical infrastructure variables (bus and subway lines, car routes, etc.); a productivity model correlating urban structure and worker characteristics with productivity; and a spatial computable general equilibrium model transforming productivity data into higher-order effects, such as growth in GDP and consumption.

“Our main datasets came from the 2010 census and an origin-destination survey conducted by the São Paulo Metro in 2007,” Haddad said. The survey data were updated for 2010, and at Agência FAPESP’s request, Haddad has now extrapolated the findings on the basis of numerical estimates for 2014 to produce a more current overview.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.