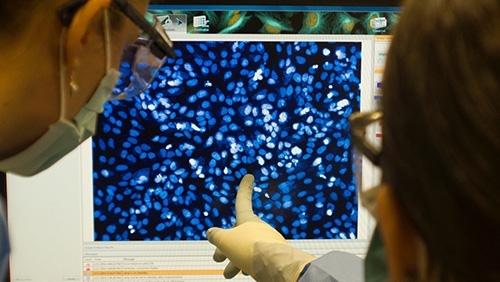

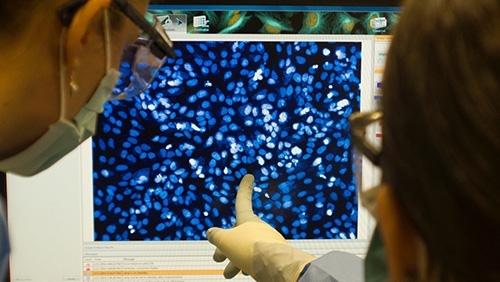

Researchers attending event say Brazil does high-level basic science in this field but lacks qualified professionals and experimental infrastructure (photo: CNPEM)

Researchers attending event say Brazil does high-level basic science in this field but lacks qualified professionals and experimental infrastructure.

Researchers attending event say Brazil does high-level basic science in this field but lacks qualified professionals and experimental infrastructure.

Researchers attending event say Brazil does high-level basic science in this field but lacks qualified professionals and experimental infrastructure (photo: CNPEM)

By Karina Toledo

Agência FAPESP – Brazil displays great potential for the discovery of new drugs to treat neglected diseases but must surmount formidable barriers, such as a shortage of professionals and experimental infrastructure, in medicinal chemistry.

This was the assessment of several Brazilian and foreign experts who spoke to Agência FAPESP during the São Paulo School of Advanced Science on Neglected Diseases Drug Discovery – Focus on Kinetoplastids (SPSAS-ND3), held in Campinas, São Paulo State, Brazil, on June 14-24.

Featuring 40 lecturers, the event was supported by FAPESP and attended by 87 students in the three main areas involved in drug discovery: chemistry; pharmacology and animal models; and parasitology and screening for new biologically active compounds.

“Medicinal chemistry needs to grow, and for this to happen, we must prepare new generations,” said Lucio Freitas Junior, a researcher at the National Bioscience Laboratory (LNBio) and a coordinator of SPSAS-ND3.

Eric Chatelain, Head of Drug Discovery at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), a Swiss-based non-profit drug research and development organization, said Brazil has good specialists in the target diseases and chemists capable of synthesizing molecules for testing but that its medicinal chemistry sector is underdeveloped.

“What’s missing is the expertise and infrastructure needed for drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics [DMPK] testing, which gives chemists crucial guidance in designing and perfecting new compounds. This is the biggest gap in Brazil,” Chatelain said. “Researchers succeed in finding hits [molecules with the biological activity of interest, such as killing a parasite] and often demonstrate activity in vivo, but they’re unable to obtain all the information required to optimize the molecule, so good compounds are wasted.”

In addition to designing the molecules that become drug candidates, medicinal chemists endeavor to understand how a substance interacts inside a biological model, which may be a cell, a laboratory animal or a human patient, said Ronaldo Pilli, a professor at the University of Campinas’s Chemistry Institute (IQ-UNICAMP), in the lecture that he delivered during the event.

To this end, medicinal chemists conduct administration, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) studies, usually in animals, to find out whether a compound that has been shown to kill a pathogen in initial screening has the other properties required for it to become a drug candidate.

“They have to see whether the compound is destroyed in the stomach or intestine, whether it’s totally metabolized in the liver, whether it’s able to reach the site of infection, whether it interacts with cells of other organs, and whether it displays any toxic activity, as well as evaluating the time that it takes to be excreted,” Pilli said. “After studying the solubility, chemical stability and metabolization of the original compound, the medicinal chemist may suggest that the organic synthesis chemist make structural modifications to the molecule to help to optimize its action.”

During the event, several specialists highlighted the importance of performing these pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics studies in the early stages of the drug discovery process.

According to Susan Charman, Director of the Center for Drug Candidate Optimization (CDCO) at the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Australia, the countries that have introduced this practice have significantly reduced the number of drug candidate failures in the clinical trial stage.

“Molecules that don’t have all the characteristics required to become drugs and the right profile to treat the target disease should be discarded as quickly as possible in order not to waste money,” said Gilles Courtemanche, Head of the Antimicrobials Unit at the Bioaster Technology Research Institute in France, in his lecture.

In Courtemanche’s view, the level of basic science in Brazil is good, but the country will not be able to make progress in drug discovery unless it strengthens medicinal chemistry and ADME. “That means training people, establishing laboratories and setting up specialized services,” he said.

According to Pilli, Brazilian universities do not have services qualified to perform ADME tests, and researchers often have to pay to have tests done elsewhere. “In academia, we see many compounds with good biological activity, and if an ADME service were available, we could do the tests and discard any compounds that weren’t genuinely interesting. However, we often have to evaluate a large number of compounds to choose the best, and if we have to pay for all the tests, the cost is extraordinary,” Pilli said.

The lack of specialized services to test the hits found by Brazilian researchers was also highlighted by Carlos Roque Duarte Correia, a professor at UNICAMP and a staff member of the Center for Research and Innovation in Biodiversity and Drug Discovery (CIBFar), which is one of the Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs) supported by FAPESP.

“Our labs have competent professionals who synthesize compounds, but we aren’t always able to find a professional for whom testing these molecules is a priority. Most of the time, these tests are performed by graduate students, so the work practically stops when they complete their master’s or PhD research,” Correia said. “The probability that a biologically active compound will have a future is tiny, but you have to try. It takes heavy investment; the awareness that this is necessary; and of course, participation by the pharmaceutical industry because no research agency could fund these studies alone.”

For Pilli, demand from the pharmaceutical industry for trained professionals is fundamental. Without it, Brazil will not be able to strengthen its medicinal chemistry sector.

Synergies

The drug discovery process is extremely multidisciplinary, involving professionals in a range of areas and subareas, from biology to chemistry to pharmaceutical sciences. The importance of integrating and coordinating the work done by each of these professionals was another difficulty highlighted by speakers at the Campinas event.

“There are many people in Brazil with the will and capacity to do the right thing,” Courtemanche. “However, there are no organizations enabling everyone to move in the same direction.”

For Freitas Junior, one possible solution would be to establish a national consortium, bringing all of the research groups who are working on the discovery of drugs for neglected diseases under one umbrella to leverage potential synergies with a common leadership.

“What happens today in the Brazilian academic environment is that individual researchers are trying to do everything on their own, from compound screening to pharmacokinetics testing and trials in animals. If the drug discovery process is to be competitive, however, all these different areas must work together, with each one bringing its expertise into the pool,” Freitas Junior said.

“We have good drug discovery initiatives here at LNBio, and several are ongoing at the National Science & Technology Institutes [INCTs], as well as FAPESP’s Thematic Projects and RIDCs. However, these people don’t talk to each other. We need to create a virtual network for exchanges of results, technology, expertise, and maybe even molecules and assays.”

Interaction among specialties

Freitas Junior said the São Paulo Advanced School that he coordinated at LNBio was structured to encourage interaction among scientists who were working in the various areas involved in drug discovery and to help them to understand the peculiarities of each specialty.

The students attending were divided into eight groups and participated in practical classes in which they learned cutting-edge techniques in compound synthesis and screening, molecule optimization, and pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics trials, among others. Part of the equipment used was brought to Brazil especially for demonstration during the event.

“We tried to demolish barriers so that everyone could put themselves in other people’s shoes and build an all-round understanding of how drug discovery is done. Brazil has much to gain in terms of qualifying its human resources, as do many developing countries with a heavy burden of neglected diseases,” Freitas Junior said.

The attendees at SPSAS-ND3 included students from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Iran, Morocco, Nigeria and Pakistan, as well as students from several Latin American and European countries, like Chiara Borsari, a 26-year-old Italian who is pursuing a PhD at the University of Modena & Reggio Emilia. “Besides learning about parasitology, I’m also finding out about several techniques that will enable me to get better and faster results in chemical synthesis,” she said.

Celestin Nzanzu Mudogo, 35, highlighted the prospects for new collaborations made possible by his participation in the event. Born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, he is currently pursuing a PhD in molecular parasitology at the University of Tübingen in Germany. “It’s good to bring together people from different areas to share problems and find joint solutions for these diseases,” he said.

Bianca Zingales, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Chemistry Institute (IQ-USP), said these students will help improve local working conditions when they return to their countries of origin.

“The professors attending this event represent the world’s leading researchers dedicated to the discovery of new drugs for neglected diseases,” Zingales said. “The techniques presented are the most advanced available. I hope the students understand the need to collaborate with more developed laboratories so that they’re able to put everything they’ve learned during the course into practice.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.