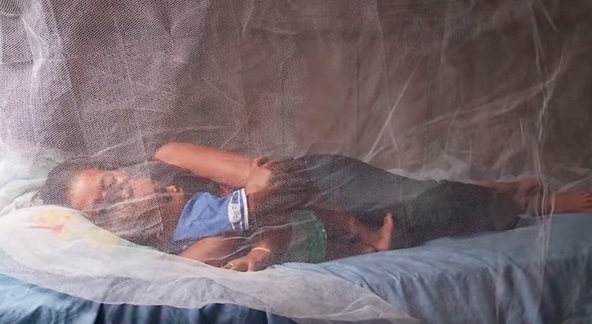

Research priorities were discussed by Keith Carter, senior advisor at PAHO-WHO, and other experts during the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences on Malaria Eradication (photo: WHO Key facts about Malaria)

Research priorities were discussed by Keith Carter, senior advisor at PAHO-WHO, and other experts during the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences on Malaria Eradication.

Research priorities were discussed by Keith Carter, senior advisor at PAHO-WHO, and other experts during the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences on Malaria Eradication.

Research priorities were discussed by Keith Carter, senior advisor at PAHO-WHO, and other experts during the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences on Malaria Eradication (photo: WHO Key facts about Malaria)

By Karina Toledo

Agência FAPESP – Brazil has been one of the leaders of the fight against malaria in the Americas and is approaching elimination of the disease, which kills about half a million people a year worldwide, most of them children under five, said Keith Carter, senior advisor on malaria and other communicable diseases at the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), linked to the World Health Organization (WHO), in his opening words to the São Paulo School of Advanced Sciences on Malaria Eradication.

Supported by FAPESP, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, PAHO and the Brazilian Ministry of Education’s Office for Faculty Development (CAPES), the event was attended by 104 students and young researchers from 42 countries. It took place at the University of São Paulo’s School of Public Health (FSP-USP) in Brazil from September 22 to October 2.

“Brazil has succeeded in significantly reducing malaria transmission in its territory and sets the world an outstanding example. Of course, there are still hurdles to surpass, especially in frontier areas,” Carter told Agência FAPESP. “In Venezuela, for example, it’s a bigger challenge than anywhere else in the Americas, and the number of cases is growing year by year.”

In his presentation to the event, Carter recalled that malaria, which is transmitted through the bites of Anopheles mosquitoes, occurred essentially throughout the world in the early twentieth century. The first global campaign to eradicate malaria was held in the mid-1950s, only a few years after the WHO was established.

The basis of the campaign was the controversial pesticide DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane). The idea was to spray all homes in all countries with DDT to reduce the density of the vector mosquito population sufficiently to break the chain of transmission.

The program eliminated the disease in Europe and North America while reducing the number of cases in other regions, but effective eradication was not as fast as expected. Moreover, consolidation and maintenance proved costly and time-consuming.

“In the mid-sixties, we began to face a shortage of funds to continue with these efforts,” Carter said. “In the next two decades, the problem was forgotten, and the number of cases started to rise again.”

According to Marcia Castro, a Brazilian-born professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in the United States, there were several reasons for the failure of that initiative.

“First of all, coverage was not complete, and the mosquito is no respecter of geographic boundaries,” she said. “If you treat one area but not all, it comes back after a time. For example, sub-Saharan Africa was left out of the initiative, and even today most cases occur in that region. Access to homes was hindered in many places by bad or no roads and a lack of well-organized health professionals.”

Another reason is the mosquito’s steadily growing resistance to DDT over the years, so that vector density could not be reduced far enough to interrupt transmission. Achievement of this goal was made even more difficult by the fact that not all patients received treatment and thus continued to serve as carriers of the parasite that causes malaria.

Eradication of research

According to Castro, the WHO’s initiative not only failed to eradicate malaria but also had a disastrous side effect: it eradicated research on the disease and training of health workers to combat malaria practically everywhere in the world.

“They thought DDT alone would solve the problem and it wouldn’t be necessary to train people or invest in a search for new control strategies and new drugs,” she said. “They overlooked the importance of studying the ecology of endemic regions and the biology of the parasite and vector mosquito.”

Efforts were not resumed until the 1990s, Castro continued, when many countries realized malaria was not just a public health issue but also an obstacle to economic development. Additionally, this was a time when globalization was at the forefront of policymakers’ concerns.

“The focus in the nineties was on controlling the number of cases so that malaria would cease to be such a dramatic health hazard,” she said. “There was no more talk of eradication, i.e., zero cases worldwide, or elimination, i.e., zero cases in a given region. A combination of measures was used, including early diagnosis and treatment, as well as vector control.”

Two steps ahead

However, experts say daunting challenges remain if malaria is at least to be kept under control, and this will only be possible through investment in research.

“The best antimalarial drug we have today is artemisinin, and there are already cases of resistance to it in Southeast Asia, where it’s been intensely used. We don’t know for sure if resistance to artemisinin has reached Africa. We’re very concerned about this possibility because no antimalarials as powerful as artemisinin are available,” Castro said.

In addition to new drugs to treat the disease, she continued, new products are needed to treat mosquito nets and spray houses because the mosquito is now resistant to widely used insecticides.

“The mosquito appears to be always two steps ahead of us,” Castro said. “It adapts both in terms of developing resistance and in behavioral terms. Books about malaria say Anopheles reproduces only in clean water, but larvae have been found in polluted water. The books say it bites indoors at night, but in the Amazon it’s begun attacking in the open at two peak times, in the early evening and early morning, when people are returning home and leaving for work.”

For Carter, anthropological research should also be conducted to understand how people live and behave in endemic areas, how they use medication, and what they do when sick.

“This kind of information is important to guide public health strategies,” she said. “We also need to understand how climate change will affect the longevity of the mosquito in various regions.”

Experts say new diagnostic methods are also needed to identify asymptomatic carriers of the parasite, as well as methods capable of diagnosing the latent form of malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax, the most prevalent species of the parasite in the Brazilian Amazon. Vivax malaria is characterized by periodic relapses, which may occur months after primary infection.

Training leaders

According to Marcelo Urbano Ferreira, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Biomedical Science Institute (IB-USP) and lead organizer of the course offered by FAPESP’s São Paulo School of Advanced Science program (SPSAS), this was the region’s first edition of “Science of Eradication: Malaria”, organized since 2012 by three global malaria research leaders: the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal, Spain), Harvard University (USA), and the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH, Switzerland).

“Originally, it was an advanced training course for health service managers or senior researchers in the area,” Ferreira said. “We adapted it for the SPSAS target audience, which includes undergraduate and graduate students as well as young researchers, some of whom are involved in malaria control programs.”

In addition to academic excellence, the selection of the 104 participants focused on assuring the presence of representatives from endemic countries, especially those that already have malaria eradication or elimination programs, such as Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Ethiopia and South Africa.

“We achieved a good balance between laboratory researchers and scholars who are also public health professionals, as well as a suitable mix of people involved in the five areas covered by the course: malaria biology and epidemiology, vector control, immunology and vaccines, treatment and new drugs, and Plasmodium biology,” Ferreira said.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.