Image: Future Cow

Future Cow uses precision fermentation to create dairy ingredients in a sustainable way; the startup, supported by FAPESP, was selected to participate in VivaTech, one of Europe’s largest innovation events.

Future Cow uses precision fermentation to create dairy ingredients in a sustainable way; the startup, supported by FAPESP, was selected to participate in VivaTech, one of Europe’s largest innovation events.

Image: Future Cow

By Roseli Andrion | Agência FAPESP – With finite natural resources and a growing demand for food, the world must find ways to overcome this challenge. One proposal comes from a Brazilian startup that will produce milk proteins without the need for cows. The company has the support of FAPESP’s Innovative Research in Small Businesses program (PIPE).

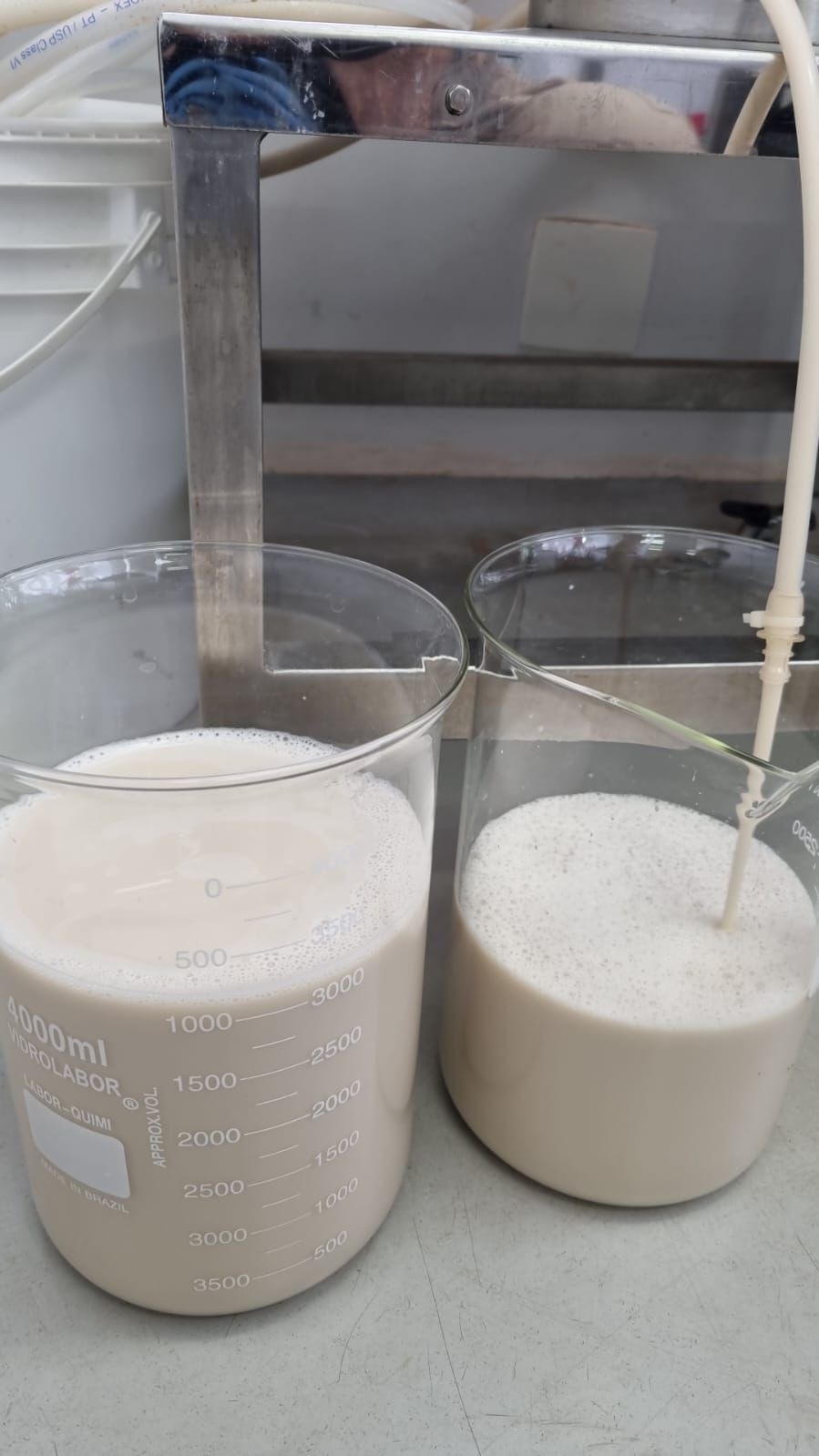

Founded in 2023, Future Cow wants to transform the dairy market by using precision fermentation, a process that combines high technology, sustainability, and production efficiency. “Our mission is to make milk without a cow,” summarizes Leonardo Vieira, the company’s co-founder and CEO. “Precision fermentation is a technology similar to that used in the production of beer or wine.”

The entrepreneur explains that the technology involves identifying the genetic sequence in the animal’s DNA that provides instructions for producing the milk protein. The sequence is then copied and encoded in a host, which can be a fungus, yeast, or bacterium. The host then multiplies in a fermentation tank with a calorie source for nutrition.

The result is a liquid that, after being filtered and dried, is transformed into the initially programmed milk proteins. “These proteins serve as ingredients for the food and dairy industry, which can recombine the product to create various derivatives,” he explains.

The foodtech will use yeast as hosts to initially produce casein and whey protein, two of the main proteins found in milk. Casein is widely used in cheese and yogurt production, while whey is rich in protein and highly valued in the food supplement market.

There are also other proteins in milk, each with specific applications. “One of them is lactoferrin, which is extremely difficult to produce using traditional methods,” says Vieira. “It takes 10,000 liters of milk to obtain just one kilo of this ingredient.”

From the laboratory to the market

Future Cow began operating in the Supera Technology Park in Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo state. There, it produced the first grams of milk protein using precision fermentation. It was then selected to take part in the DeepTech Acceleration Program (PACE) of the Brazilian Center for Research in Energy and Materials (CNPEM) in Campinas.

It is now testing the scaling of the process, which is a critical stage for biotech companies. “Ninety-five percent of biotechs fail when they leave a bench environment and go to a pilot plant or other relevant environment,” recalls Vieira. “We’re very optimistic that, with the support of the CNPEM and the available infrastructure, we’ll achieve the scale-up we need for the next stage.”

The startup does not intend to replace animal milk entirely; rather, it wants to create complementary solutions for the industry. “When precision fermentation began, it was all very black or white: the product is either animal or it isn’t animal. Now, we see more hybrid models,” he observes.

According to Vieira, executives from large dairies claim to already purchase all the available milk on the market. “They can’t increase production by 20 or 30 percent with just the traditional raw material,” he says. “If they can mix our ingredient with the animal product to create a hybrid product and increase the scale, it’ll be a significant gain,” he says.

Another relevant aspect is the decarbonization agenda of large companies. “Even if precision fermentation doesn’t fully replace animal milk, a 10 or 20 percent reduction in the carbon footprint of large corporations in the food sector would already represent a considerable environmental impact.”

Brazilian potential

The sector for alternative proteins produced by precision fermentation is still in its early stages, but startups specializing in the segment are already emerging around the world. “Each one follows a different technological route. There’s variation in the type of host [fungus, yeast, or bacteria] and in the target proteins,” details Vieira.

The entrepreneur points out that Brazil is in a privileged strategic position to lead the global market. “Brazil is the only country in the world that has an abundance of water, sugar, and renewable energy, which are the three essential inputs for fermentation. It’s a unique opportunity for the country,” he points out. “With these characteristics, Brazil can take the lead in a strategic industry for the future of global food.”

Future Cow’s technical and economic analyses show that producing milk proteins on a 300,000-liter scale will be less expensive than traditional production methods. He points out that, when precision fermentation reaches an industrial scale with lower costs, it will disrupt the market. “If Brazil only focuses on traditional agriculture at that point, we’ll be left behind.”

The researcher cites New Zealand as an example. The country has characteristics similar to Brazil’s, and a significant portion of its gross domestic product (GDP) comes from milk exports. “They’ve already realized that the sector is going to change and are moving to avoid being left behind,” he comments. “I’ve been trying to alert the Brazilian government authorities to this potential.”

Future prospects

Future Cow already has a functional strain and is now looking to increase production yields. “The more the strain produces, the more the unit price falls. So we’re optimizing the fermentation processes.” The expectation is that the product will be ready and available for sale by the end of 2026.

Since the product is an ingredient, the company will not sell directly to the end consumer but rather will act as a supplier to the food industry. This approach could facilitate the startup’s entry into the market. “As an ingredient, our product can be incorporated into existing products without facing a high entry barrier.”

The startup will initially market the proteins it has already developed before expanding to other varieties. “Only after the first commercialization will we develop other proteins,” says the entrepreneur.

The company is preparing to take part in VivaTech, an innovation fair that will be held in Paris, France, in June. “The technology already exists in other countries and at VivaTech we’ll be able to show that Brazil has it too,” says Vieira. “We can win over investors who realize that we can manufacture in Brazil and export to other locations. This kind of exposure abroad is uncommon for Brazilian companies.”

At the meeting, Future Cow aims to connect with the innovation ecosystem, raise awareness of the development of the technology in Brazil, and attract potential corporate partners. “We want to demonstrate that we’re developing alternative proteins and, with this, attract multinationals from the dairy sector to be our clients.”

Scientific entrepreneurship

One aspect that Vieira highlights is the combination of skills at Future Cow: while he brings experience in business and entrepreneurship, his partner, Rosana Goldbeck, has a Ph.D. in food engineering from the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and has already studied meat cultivation in Brazil. “This mix is an important differentiator, as it brings together someone who understands business and someone who understands the technology.”

According to Vieira, this is one of the main barriers preventing more innovations from Brazilian universities that become commercial products. “Brazil produces a lot of science, has many scientific articles, but most of them don’t become businesses,” he laments. “There need to be more connections between the academic environment and entrepreneurship in Brazil.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.