Sherry Turkle, a specialist in relations between technology and society at MIT, warns about the risk of hoping that robots and artificial intelligence products will resolve relationship problems or cure loneliness

Sherry Turkle, a specialist in relations between technology and society at MIT, warns about the risk of hoping that robots and artificial intelligence products will resolve relationship problems or cure loneliness.

Sherry Turkle, a specialist in relations between technology and society at MIT, warns about the risk of hoping that robots and artificial intelligence products will resolve relationship problems or cure loneliness.

Sherry Turkle, a specialist in relations between technology and society at MIT, warns about the risk of hoping that robots and artificial intelligence products will resolve relationship problems or cure loneliness

By Heitor Shimizu, from Boston

Agência FAPESP – “What are we talking about when we talk about robots?” asks Sherry Turkle of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), paraphrasing the famed short story “What we talk about when we talk about love,” by Raymond Carver (1938-1988), about the ups, downs, subtleties and uncertainties of love.

Turkle is a professor of Social Studies in Science and Technology and directs a research program at MIT about human relations with technology. The author of science best-sellers like The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit (1984) and Simulation and Its Discontents (2009) was one of the main attractions at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), held February 14 – 18 in Boston, Massachusetts, when she spoke to an audience of 1,200 people.

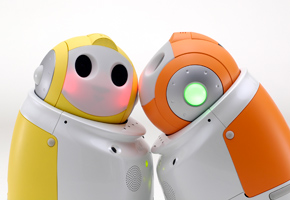

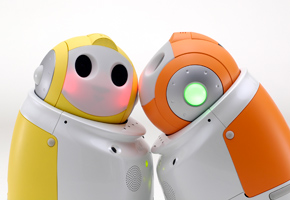

No longer a fixture of cinema, robots are found working in factory assembly lines, performing deep-water ocean explorations and engaging activities that would be dangerous to humans, such as working in volcanoes or nuclear plants with leaks. But Turkle is not at all interested in these types of machines; her focus is on robots projected for relationships with people.

“We are in what I call a ‘robotic moment.’ That is not because we have built robots worthy of our company, but because we are ready for their company,” said Turkle. This is a scenario that brings optimism, but also risks, according to the scientists.

Turkle cited Wired magazine, whose January cover story “celebrated how robots are replacing us.” These machines include robots in the form of toys, dolls, pets and nurses to care for the sick as well as products with artificial intelligence, not only in the traditional humanoid forms, but also those that are both imperceptible and omnipresent, like Siri, which is a feature of new iPhones and iPads that responds to users’ requests.

“The message of the report is a typical example of how the subject has been treated for decades. It is a two-part argument. In the first, the robots become more human in expanding relationship alternatives since we can now relate to them. In short, they are a ‘new species.’ The second part of the argument is that it does not matter what people do; if a robot can be put in that role, by definition, the role is not human. And this includes the task of talking to or taking care of a person, for example,” says Turkle.

“I lecture at MIT, where many people agree with this position. This means that some of my most brilliant colleagues have investigated the issue of robots as human company for years. One of my students even used the voice of his daughter for a robot doll he developed, My Real Baby, a success that is being marketed for its ability to teach socialization skills,” she explained.

“It was at MIT that I had of the idea of social robotics, through which researchers imagine robots as teachers, assistants and best friends for lonely people, whether young or old. In a study that I conducted on the topic, one of the interviewees stressed that he would prefer to have a robot take care of his elderly mother than to hire an unknown person. Another stated a preference for a robot over an untrusted babysitter,” she said.

Turkle posits that there are many ways that robots or artificial intelligence systems can or cannot be useful in day-to-day life, but she warns about the risk of being too dependent on the possibilities created by technology. Robots are machines, not substitutes for people.

“So, what are we talking about when we talk about robots? We are talking about our own fears and deceptions regarding others and ourselves. We are talking about a lack of community. Of our lack of time. People dream about robots that resolve their individual problems and their relationship difficulties,” says Turkle.

“But I see a different path. I hope that when talking about the mistake of imagining salvation through the company of robots, I can cast a shadow over this enchantment. Perhaps we can dedicate ourselves to the potential of robotic technology that can help us in different ways, or simply dedicate ourselves to developing this potential within ourselves. My main reservation with regard to artificial friends is very simple: if we spend time with them, we spend less time with each other, or with our parents, children or friends,” she said.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.