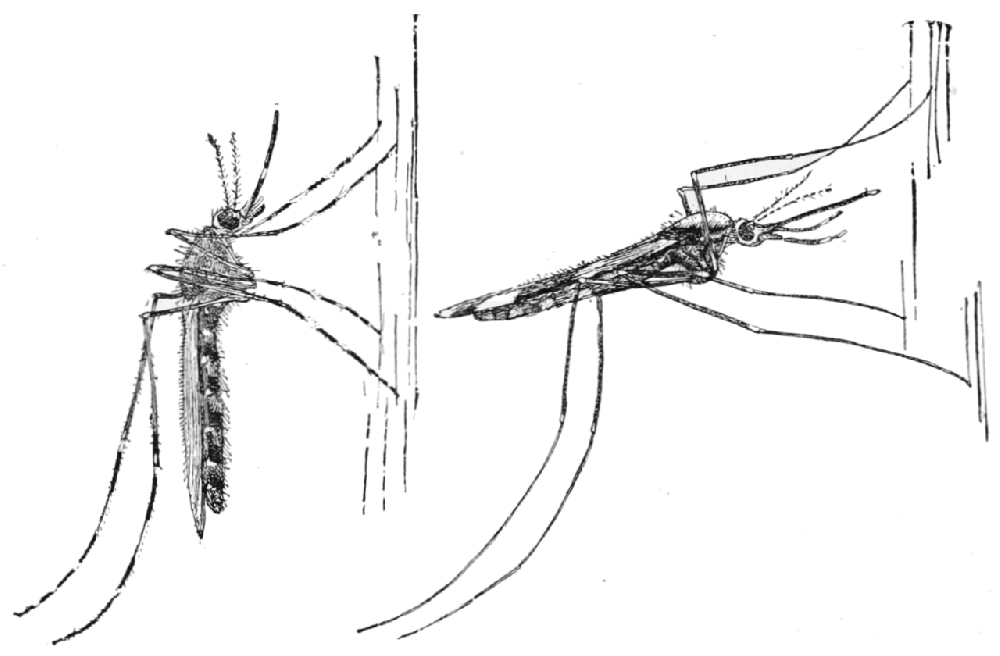

Using GPS data from smartphones, new tool promises to identify disease hotspots and help stop transmission (image: Culex / Wikimedia Commons)

Using GPS data from smartphones, new tool promises to identify disease hotspots and help stop transmission.

Using GPS data from smartphones, new tool promises to identify disease hotspots and help stop transmission.

Using GPS data from smartphones, new tool promises to identify disease hotspots and help stop transmission (image: Culex / Wikimedia Commons)

Agência FAPESP – Helder Nakaya, a researcher in the Department of Clinical & Toxicological Analysis at the University of São Paulo’s School of Pharmaceutical Sciences (FCF-USP), has designed an application to map tropical disease hotspots by aggregating data on cases of dengue, malaria and Zika, among others. The software will locate symptomatic cases, act as an aid for health workers, and contribute to a reduction in the incidence and transmission of these diseases.

The application will work as follows. Symptomatic patients diagnosed with Zika, dengue, tuberculosis, leishmaniasis, chikungunya, parvovirus and malaria at reference hospitals will voluntarily provide their smartphone’s location history, making it possible to map where they have been in the preceding two-week period. The program will use these datasets to list and correlate the points in common visited by the volunteers, thus identifying hotspots.

The app to be based on this information will show disease hotspots in the participating cities, and health workers will go to these places to collect blood samples to identify asymptomatic cases. Measures can be taken more quickly to contain transmission if this information is available.

According to Nakaya, a co-principal investigator at the Center for Research on Inflammatory Diseases (CRID), one of FAPESP’s Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs), smartphone GPS systems have a high level of precision, corresponding to a radius of about 1 m. This resolution ensures the quality of the project. “The difference compared with existing apps involving photographs sent by users to register mosquito breeding grounds is the accuracy of the data. We’re doing a lot of tests to ensure the information is as precise as possible,” he says.

He guarantees that there will be no risks to privacy, as location histories will consist only of coordinates, and no contact details or photographs will be stored in the database. “One of the challenges of our project is people’s distrust when we ask for location history. We’re taking every possible precaution to make sure we have no access to email addresses, photos or even names,” he says.

The following cities will receive the initial map of hotspots to test the app: São Paulo, Recife, Manaus, Goiânia, João Pessoa, Belém, Campinas, Salvador, Aracaju, São João Del Rey, Ribeirão Preto, Belo Horizonte, São José do Rio Preto and Porto Velho.

The mapping of malaria transmission hotspots in Manaus is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation via Grand Challenges Explorations (GCE), an international program that awards grants of US$100,000 in support of innovation to solve key global health and development problems. If the project is successful, Nakaya can apply for an addition grant of R$1 million to extend the app’s scope even farther.

The project is currently in the testing stage. Nakaya has put up a website that is running a pilot to test the use of GPS data from cellphones and to recruit health researchers, students and nurses. Volunteers will be contacted to be told about next steps, with a strong emphasis on privacy and data confidentiality.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.