An international research group produced high-resolution charts of a canyon with a depth of up to 3,000 m in Ireland to help understand global climate change (photo: University College Cork)

An international research group produced high-resolution charts of a canyon with a depth of up to 3,000 m in Ireland to help understand global climate change.

An international research group produced high-resolution charts of a canyon with a depth of up to 3,000 m in Ireland to help understand global climate change.

An international research group produced high-resolution charts of a canyon with a depth of up to 3,000 m in Ireland to help understand global climate change (photo: University College Cork)

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – On August 10, 2018, the RV Celtic Explorer, an Irish research vessel, returned to Galway Harbor on the west coast of the Republic of Ireland with unique high-resolution charts of a deep-sea canyon.

The expedition was part of an international project whose participants included Luis Americo Conti, a researcher at the University of São Paulo’s School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities (EACH-USP) in Brazil. One of the goals of this project was to achieve a better understanding of the role of cold-water corals in capturing carbon from the atmosphere.

“The corals live at the top of the canyon, and as they die, their fragments fall to the ocean bed. The carbon they absorbed during their lifetime remains in the debris and is eventually transferred to sedimentary deposits,” said Conti, whose study was supported by FAPESP.

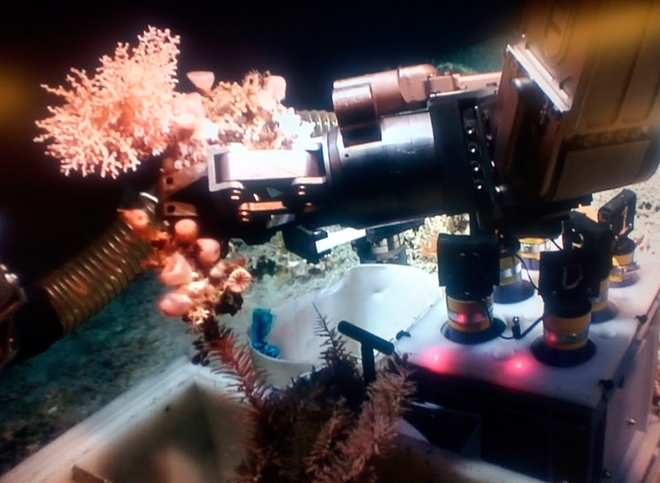

The two-week expedition mapped the entire area of the Porcupine Bank Canyon in Ireland, which totals 1,800 square kilometers, an area larger than São Paulo City, using high-resolution sonar and a remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV).

Although the canyon’s depth reaches 3,000 m, the Holland I ROV dove to approximately 2,000 m, where the most recent coral rubble is located.

“The samples collected by the ROV will be used to analyze the dynamics of this phenomenon over the past 10,000 years and may give us clues to understand current climate change,” Conti told Agência FAPESP.

In addition to taking cores of coral-rich sediment from the bed of the canyon, the ROV brought back samples of live coral from the walls and top of the canyon. These samples will be analyzed by biologists, who will attempt to identify the species that inhabit the area and their kinship to species found in other regions.

The ROV also collected video recordings of coral colonies to complement the sonar mapping survey performed by the research vessel. As a result, the researchers will be able to establish correlations between the topographic charts of the canyon and the areas colonized by corals.

“This is a vast submarine canyon system, with near-vertical 700 m cliffs in places and going as deep as 3,000 m. You could stack ten Eiffel Towers on top of each other in there,” said expedition leader Aaron Lim, a researcher at University College Cork’s School of Biological, Earth & Environmental Sciences (BEES-UCC) in Ireland.

Stored carbon

Unlike warm-water corals, which obtain nutrients by symbiosis with microscopic algae (zooxanthellae) that live in their tissues, cold-water corals such as those in the Porcupine Bank Canyon depend on dead plankton sinking from the surface.

“In deep waters such as these, there’s not enough light for algal photosynthesis and there are insufficient nutrients. Canyons are ideal because the marine currents are more intense in them and they transport lots of organic matter, which is filtered by the coral,” Conti said.

“The corals get their carbon from dead plankton raining down from the ocean surface, so ultimately from our atmosphere,” said BEES-UCC Professor Andy Wheeler, who is affiliated with the Irish Center for Research in Applied Geosciences (iCRAG).

“Rising CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere are causing extreme weather. Oceans absorb this CO2, and canyons are a rapid route for pumping it into the deep ocean where it’s safely stored away.”

Analysis of the cores and other samples should enable researchers to determine whether atmospheric levels of CO2 influence the growth and death of coral colonies. The canyon was stable at the time of the survey, but violent events periodically rip up and erode the seabed.

“They’re called pulse events,” Conti said. “In some places, such as Norway, avalanches of dead coral occur in submarine canyons. In others, there are slower but constant movements.”

Conti’s goals also included learning about more advanced mapping techniques to use them in research projects in Brazil.

“The Brazilian continental shelf is being more thoroughly explored. The Alpha Crucis, one of the University of São Paulo’s research vessels [purchased with FAPESP’s support], has appropriate equipment for submarine mapping. This isn’t a lot, but it’s a good start. The discovery of corals at the mouth of the Amazon River was also an important achievement.”

However, more detailed mapping projects are required, according to Conti, including a systematic topographical survey of the Brazilian seabed.

“Ireland carried out a major seabed survey approximately 15 years ago. It was thanks to this operation that they discovered this canyon, which has now been chosen for detailed research as a natural laboratory,” he said. “Without something like that, we’ll be two steps behind.”

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.