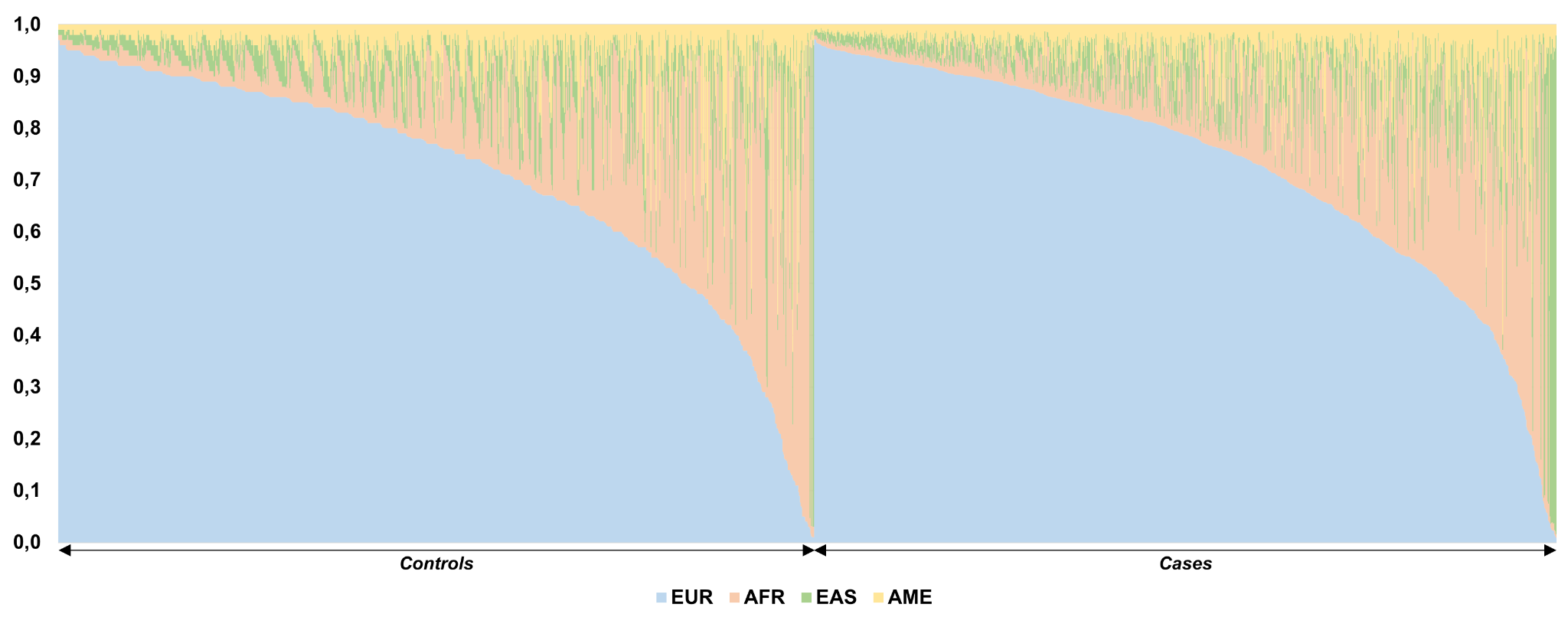

Genetic ancestry of cases (right) and controls (left), showing the proportion of the four populations for each individual (EUR – European; AFR – African; EAS – East Asian; and AME – Amerindian)/credit: Global Oncology

The disease is the third most common type of cancer in Brazil, excluding non-melanoma skin tumors. Between 5% and 10% of cases are hereditary.

The disease is the third most common type of cancer in Brazil, excluding non-melanoma skin tumors. Between 5% and 10% of cases are hereditary.

Genetic ancestry of cases (right) and controls (left), showing the proportion of the four populations for each individual (EUR – European; AFR – African; EAS – East Asian; and AME – Amerindian)/credit: Global Oncology

By Fernanda Bassette | Agência FAPESP – One of the largest Brazilian studies on colorectal cancer has revealed how genetic variations and genetic ancestry can influence the risk of developing the disease. The study, conducted by researchers at Hospital de Amor (formerly Hospital de Câncer de Barretos, in the interior of the state of São Paulo) and other institutions and funded by FAPESP, contributes to understanding the complex genetic reality of a highly mixed population such as Brazil’s. It was published in the journal Global Oncology.

Colorectal cancer is becoming increasingly common among young adults. According to the latest estimates from the National Cancer Institute (INCA), it is expected to affect around 46,000 Brazilians between 2023 and 2025. When excluding non-melanoma skin tumors, colorectal cancer ranks third among the most common types of cancer in the country. This is why researchers have focused their efforts on better understanding the factors that influence its development.

Approximately 5% to 10% of cases have a clear hereditary origin caused by germline mutations inherited from parents. The remaining 90% are considered sporadic and are mainly related to environmental factors and lifestyle, although genetic makeup also plays a role. Based on this, the researchers sought to determine whether individual genetics plays a role as a risk or protective factor in the development of the disease among these non-hereditary cases.

To reach their conclusions, the researchers analyzed 45 polymorphisms (genetic variants known as single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs]) reported in the scientific literature as being associated with the development of colorectal cancer. They sought to determine if these genome variants were also associated with the risk of colorectal cancer in Brazil. “The variants were previously identified in studies with European and Asian populations. We studied them specifically in our population,” says Rui Manuel Reis, scientific director of the Teaching and Research Institute at Hospital de Amor and author of the study.

The study involved 1,933 individuals, including 990 patients with colorectal cancer and 1,027 people with no history of the disease. In addition to genotyping the 45 genetic variants in the participants’ blood samples, the team also assessed their genetic ancestry using a panel of 46 informative markers that can accurately identify the proportion of European, African, Asian, and indigenous ancestry in each person.

“The IBGE [Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics] asks about skin color, but this is a very subjective criterion. We use much more objective and accurate markers to identify the proportion of ethnic ancestry of each person participating in the study,” Reis explains.

Variants that stand out

Of the 45 variants analyzed, nine showed a significant association with disease risk. Four of these variants maintained their relevance even after multivariate analyses were adjusted for clinical and epidemiological factors. Two variants were associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer, while two others were associated with a decreased risk, i.e., they showed a protective effect.

These variants are located in regions of the genome associated with the regulation of inflammatory processes and cell growth. “Our study demonstrated that these four markers, on their own, are independent of all other variables studied and alone contribute to the risk or protection of the disease,” says Reis. “It’s important to note that these aren’t somatic genetic mutations [which only affect the tumor], but rather normal genetic variations that contribute to our characteristics and make us unique, such as skin color. We’re born with them,” he says.

Role of ancestry

Another innovative finding of the study was to identify the role of genetic ancestry in the risk of developing the disease. The researchers found that individuals with lower proportions of African and Asian ancestry were at higher risk of developing colorectal cancer. This data reinforces the hypothesis that certain genetic components inherited from these populations may have a protective effect.

“We observed that the population with greater Asian or African genetic ancestry had a lower risk of colorectal cancer. This is something that’s already been observed in international studies, and our analysis confirmed that this pattern is also repeated in the Brazilian population,” Reis points out.

The researcher says the association may have multiple explanations. One possibility is that the genetic factor is intertwined with socioeconomic and cultural determinants. “It’s possible that people with Asian ancestry, for example, have different eating habits – more vegetables, more fish, less red meat – and this is a protective factor,” he says. “What we’re seeing may be a reflection not only of genetics, but of a set of factors,” he adds.

According to the researcher, the main difference in this study is the sample size – one of the largest ever used in a study of this type in Brazil – and the representativeness of the population analyzed. “Most previous studies were conducted with small groups, with limited statistical power. We worked with almost 2,000 people from all regions of Brazil, which ensures greater ethnic diversity,” he points out.

Personalization in the future

Reis also emphasizes the potential for applying the findings to personalized medicine. While the genetic variants identified cannot be modified – after all, they are inherited from our parents – knowledge about them may help personalize screening and prevention strategies in the future.

“Genetic risk isn’t everything. Obesity, for example, can increase the risk of colorectal cancer by up to two times. But if a person has one of these risk-associated variants, coupled with an unhealthy lifestyle, the total risk increases,” he warns. “Our future goal is to combine these genetic data with environmental factors to create a more effective and personalized screening strategy. Perhaps people with these variants should be prioritized in screening programs and made more aware of modifiable risk factors.”

The team is currently working on a new phase of the study. While the previous phase analyzed 45 variants known in the international scientific literature, the next phase will map up to three million genetic variations in Brazilians. “We want to create a specific risk score for our population that takes into account our unique characteristics. This could represent a significant advance in combating the disease in Brazil,” he says.

By gathering data representative of Brazilian genetic diversity on an unprecedented scale, the study emphasizes the importance of responding appropriately to Brazil’s unique circumstances. “Much of the research is done on North American or European populations, which have low genetic diversity. Our study offers a new perspective. It shows that the genetics of our population can help us better understand the diseases that affect us,” says the researcher.

The article “Association of genetic ancestry and colorectal cancer risk in a large Brazilian cohort: replication of single-nucleotide polymorphisms identified by genome-wide association studies” can be read at ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/GO-24-00512.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.