Research points to the occurrence of a single adaptive event before the first Americans spread over the Americas. The study published in PNAS involved scientists from Brazil, the United States and Spain

Research points to the occurrence of a single adaptive event before the first Americans spread over the Americas. The study published in PNAS involved scientists from Brazil, the United States and Spain.

Research points to the occurrence of a single adaptive event before the first Americans spread over the Americas. The study published in PNAS involved scientists from Brazil, the United States and Spain.

Research points to the occurrence of a single adaptive event before the first Americans spread over the Americas. The study published in PNAS involved scientists from Brazil, the United States and Spain

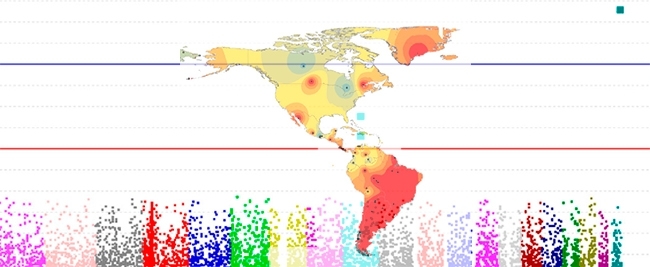

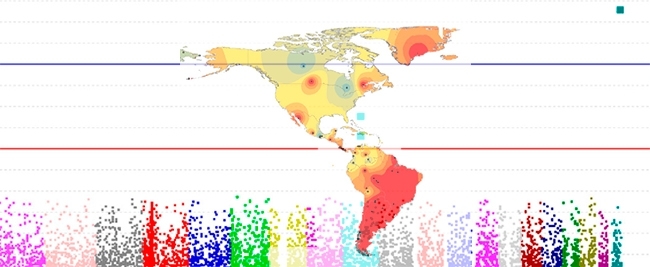

By Peter Moon | Agência FAPESP – Scientists from Brazil, the United States and Spain have discovered evidence of natural selection in a certain type of gene found not only in an Arctic population, as was already known, but in all Native Americans. This discovery suggests a single adaptive event in a common ancestral population that occurred before the range expansion of the first Americans over North and South America.

This evidence has to do with the evolution in humans of genes for fatty acid desaturase (FADS), a type of enzyme required for the digestion of food rich in unsaturated fat, such as the seal and whale meat consumed by the Inuit who live in the Canadian Arctic and Greenland.

This genetic adaptation in the Inuit was discovered by an international team of researchers in 2015. After reading their published paper on the study, Tábita Hünemeier, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Bioscience Institute (IB-USP) in Brazil, decided to find out whether the same adaptation was present in the genes of other Native Americans.

Hünemeier and collaborators recently confirmed the existence in Native Americans alive today of a positive gene signature for adaptation to the consumption of lipids. The study, whose results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was supported by FAPESP.

“When I saw the article about Inuit adaptation to a high-fat diet, I was surprised not by the occurrence of genetic adaptation but by the fact that it occurred among the Inuit,” Hünemeier said. “In evolutionary terms, the Inuit are a very recent population. They’ve only been in Greenland and Canada for 6,000 years. That’s not a long period for a genetic adaptation to create variability within a population.”

The Inuit are descendants of a second wave of human migration into the Americas that occurred 6,000 years ago and was restricted to the Arctic. Starting from a genetic comparison of populations, the authors of the study focusing on Inuit DNA found positive evidence of adaptation to lipid consumption in genes on chromosome 11.

“The authors compared the Inuit genome only with the DNA of Chinese and European people. They ignored Native Americans,” Hünemeier said.

Therefore, she decided to scrutinize the genomes of Native Americans and populations in other parts of the world in search of evidence that pointed to adaptation to fat consumption. She was assisted by two postdoctoral students, Carlos Eduardo Amorim and Kelly Nunes, who had a scholarship from FAPESP.

Nunes explained the technique used in the analysis. “First, we compared the Native American genome with the genomes of Africans, Europeans and Asians to see which alleles were highly frequent in Native Americans and infrequent in the rest,” she said.

The researchers found three DNA sequence variations in Native Americans, called single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, pronounced “snips”).

“Two significant SNPs were in chromosome 11 and a third in chromosome 22,” Nunes said. The next step was to find out whether the variations were linked to the evidence of positive selection for lipid desaturation. The results pointed to two chromosome 11 SNPs in Native Americans located at the same site as the positive signal for lipid desaturation in the Inuit genome.

“These mutations are linked to metabolic problems that are highly frequent in Native Americans and infrequent in the rest of the world,” Hünemeier explained.

Given that Native Americans and the Inuit have the same positive signal, the researchers concluded that both are descendants of the same ancestral population that lived in Beringia, the unglaciated land extension also known as the Bering land bridge, which joined Siberia to Alaska during the glaciations and is thought to have risen from seas drained by the water-locking effect of spreading ice caps.

Positive signal

It remained to be seen whether the signal had appeared in the Native American genome by “neutral selection” – i.e., as a result of random genetic processes – or by natural selection, in which individuals carrying the genetic mutation that enabled them to consume fatty meat obtained an adaptive advantage over others.

“All the evidence points to a natural selection event,” Hünemeier said. Selective pressure in Beringia must have led to a process through which individuals with the lipid desaturation gene left more descendants than those without the mutation, she added.

“The signal is too strong to have originated in a neutral selection event,” Nunes stressed. “Our study showed it was a selective signal.”

The researchers inferred that pressure to adapt to consuming fatty meat must have occurred in Beringia because the positive signal for lipid consumption was not found in the fossil DNA of a Siberian who died approximately 20,000 years ago.

Archeologists and paleoanthropologists have long inquired into the origins of the first humans to populate the Americas, particularly after artifacts of the Clovis people were found in the Southwestern United States in the 1930s.

Many discoveries have since been made, raising several hypotheses and new questions. Thanks to the advent of molecular biology, it is now estimated that the Paleoamericans remained confined to Beringia for approximately 5,000 years because Canada was covered by glaciers that prevented the migrants from moving further south.

According to Hünemeier, most researchers interested in the peopling of the Americas agree that genetic differentiation of extant Native American populations is likely to have occurred during their forced stay in Beringia, to which migrants arrived from different parts of Asia some 23,000 years ago and where they remained for 5,000-8,000 years.

As a result, the ancestors of today’s Native Americans had time to adapt to the new continent before the glaciers began to melt, in a process that began 15,000 years ago. This was when a land corridor opened up between the Canadian glaciers, allowing the settlement of the rest of the Americas. Beringia disappeared 12,000 years ago, when sea levels rose due to the end of the ice age.

The article “Genetic signature of natural selection in first Americans” (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620541114) by Carlos Eduardo G. Amorim, Kelly Nunes, Diogo Meyer, David Comas, Maria Cátira Bortolini, Francisco Mauro Salzano and Tábita Hünemeier was published in PNAS and can be retrieved from pnas.org/content/early/2017/02/07/1620541114.short?rss=1.

Republish

The Agency FAPESP licenses news via Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) so that they can be republished free of charge and in a simple way by other digital or printed vehicles. Agência FAPESP must be credited as the source of the content being republished and the name of the reporter (if any) must be attributed. Using the HMTL button below allows compliance with these rules, detailed in Digital Republishing Policy FAPESP.